This story was written by Danielle Ivory.

Results from a federal drinking water monitoring program show that many public water companies are ineffective at removing a widely used weed-killer from their water supplies.

As the Huffington Post Investigative Fund reported earlier this week, the Environmental Protection Agency has failed to notify the public about data showing that the herbicide atrazine has been found at levels above the federal safety limit in drinking water in at least four states.

But that data also reveals that many public water filtration systems are not removing the herbicide. In many places, atrazine levels in untreated water sources such as rivers directly match the levels that come out of the tap.

A carbon filter with granular activated carbon — in other words, a giant Brita-like filter — should absorb all or most of the atrazine. But the EPA’s atrazine monitoring data shows that many water utilities in the Corn Belt do not use carbon filtration. Many use rapid sand filters instead. They are cheaper and last longer, but are unable to remove organic compounds such as PCBs, phthalates, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides such as atrazine.

“Carbon filters might have to be replaced every couple of years whereas sand filters could last 20 to 30 years,” said Alan Roberson, director of security and regulatory affairs at the American Water Works Association, a non-profit organization representing water utilities.

To recover the cost of filtering atrazine, water companies in six states are preparing a lawsuit against the makers of atrazine, the Swiss company Syngenta.

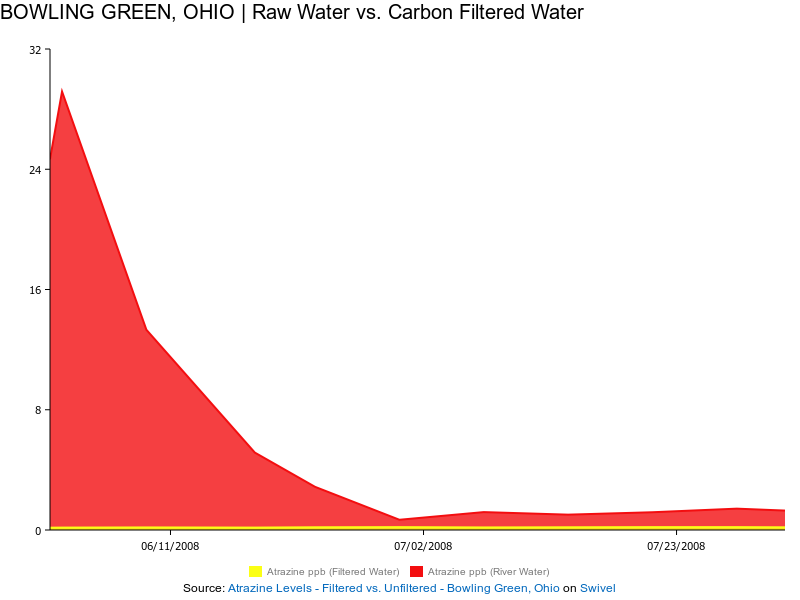

When you compare the raw and finished water of an effective carbon filtration system, you see something like the chart below, which shows weekly levels of atrazine in river water and drinking water as measured last year in Bowling Green, Ohio.

Bowling Green added carbon filters to the water system in 2000. “We installed the filters to take care of taste and odor problems, but it [also] gets the atrazine out of there,” said Chad Johnson, assistant superintendent at the water utility. “These filters are expensive, though. Our new building cost about five million dollars.”

Bowling Green added carbon filters to the water system in 2000. “We installed the filters to take care of taste and odor problems, but it [also] gets the atrazine out of there,” said Chad Johnson, assistant superintendent at the water utility. “These filters are expensive, though. Our new building cost about five million dollars.”

Every year, the utility replaces six of the 12 filter vessels at a cost of $126,000, Johnson said. He said the water plant had received $5 million in stimulus funds, which will be used to partially fund an $11 million project to install new membranes, which will remove nitrates and other chemicals from the water.

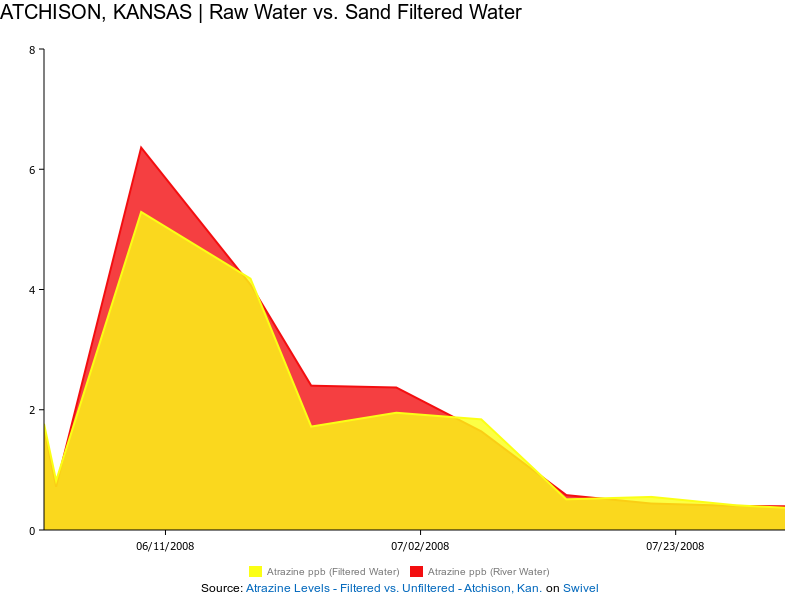

Atchison, Kan., is among water systems that do not have adequate filters in place. The chart shows weekly levels of atrazine in river water and drinking water as measured last year.

“I’ll be darned,” said Michael Matthews, the utilities director in Atchison, Kan., upon hearing that atrazine was barely being filtered from his drinking water. “That’s bad.”

“I’ll be darned,” said Michael Matthews, the utilities director in Atchison, Kan., upon hearing that atrazine was barely being filtered from his drinking water. “That’s bad.”

Water plant managers said the economic downturn has made it even harder to convert to more effective filters. “Right now, we can’t afford anything,” said Lloyd Littrell of the Beloit, Kansas water plant, where rapid sand filters are used.

“It’s impossible to get atrazine out of the water with these filters. There’s no way to remove it,” he said. “But people need this water. We can’t just shut our doors and tell people to drink from the river.”

Stan Schafer of the Baxter Springs plant, where sand filters are used, said it was difficult to get funding for water cleanup even prior to the recession. “Shoot, I’d like another filter,” he said. “But they’re expensive. We did a $2.5 million update about three years ago and that system is falling apart.”

A civil engineering professor at Virginia Tech University, Marc Edwards, said that the cost of granular activated carbon treatment could double the total cost of drinking water treatment in some rural and poor communities.

“We are used to paying very little for tap water,” Edwards said. “It is hard for some rural communities to justify the higher costs of advanced treatment.”

“Most water systems don’t have the resources to buy a new filter,” said Kirk Leifheit, Assistant Chief of the Drinking Water Program at the Ohio EPA. “They are reporting to us needs in the billions.”

The EPA only monitors the river water and drinking water in about 150 water systems, so it is unknown whether other communities might be experiencing problems filtering atrazine. Washington, D.C., and Maryland, for example, are not part of that program.

However, atrazine is heavily used in the Maryland area, according to data from the U.S. Geological Survey. The Washington Aqueduct, which treats water from the Potomac River for about 1 million in the D.C. area, does not filter for atrazine.

Water systems in 57 cities are preparing a lawsuit against the atrazine manufacturer, the Swiss company Syngenta, to recover the cost of filtering the chemical out of drinking water. Utilities in Illinois, Ohio, Kansas, Indiana, Missouri, and Iowa are preparing to file suits in state courts. A hearing in Illinois is scheduled for Monday.

“Many of those water providers have incurred an enormous amount of expenses at a time when their tax base is shrinking,”said Stephen Tillery of the Korein Tillery law firm in St. Louis, who represents the water systems. “They’re cash strapped.”

Jere White, executive director of the Kansas City Corn Growers Association and the Kansas Grain Sorghum Producers Association, has been fighting atrazine regulation at both a local and national level since 1995. He has been vocal about opposing the class action lawsuit against Syngenta.

“The difference between them [the lawyers] and an ambulance chaser is the fact that with an ambulance chaser, you at least assume that there’s an ambulance and an injury,” White said in a phone interview.

White is also chairman of the Triazine Network which has been fighting atrazine regulation since 1995. The Network and the Corn Growers, according to White, receive regular funding from Syngenta — for travel, speaking engagements (including EPA hearings), and education, though he pointed out that it has never been earmarked specifically for “advocacy.” The Network, according to its website, “strives to keep the beneficial triazine herbicides available in the United States.”