Photo by KalaLeaThe next time you bite into a burger, consider this: Livestock create more greenhouse gas emissions than all the cars, trucks, planes, and other fossil-fueled modes of transportation in the world. In fact, our current food system—from industrial farming to packaging to transporting—contributes as much as one-third of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Photo by KalaLeaThe next time you bite into a burger, consider this: Livestock create more greenhouse gas emissions than all the cars, trucks, planes, and other fossil-fueled modes of transportation in the world. In fact, our current food system—from industrial farming to packaging to transporting—contributes as much as one-third of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Food’s critical place in the climate-change equation is not common knowledge. But author Anna Lappé is doing her best to change that.

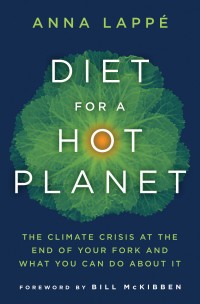

Lappé cofounded The Small Planet Institute with her mother, Frances Moore Lappé, author of the 1971 classic Diet for a Small Planet. And Anna Lappé’s new book, Diet for a Hot Planet: The Climate Crisis at the End of Your Fork and What You Can Do About It, picks up where her mother left off nearly 40 years ago, shining a light on the dangerous impacts of our flawed food system on our fragile, warming planet. Lappé chatted with me recently from her home in Brooklyn about corporate greenwashing, what her baby eats, and how to help people find the lost connection between nature and food.

Q. Why do you think this food-climate connection hasn’t really been made until recently?

A. First and foremost, it comes down to the fact that the broader climate change conversation is such a relatively new public conversation. As we began to wrap our minds around climate change, we first focused on some of the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions. It made sense that we would be talking about coal-fired plants in the energy sector. Now here is broader consensus that this is a crisis, and we understand that every sector needs to play a role.

The second core reason goes back to a historic disconnect between the environmental movement and food. Most of the large, mainstream environmental organizations in this country have largely been silent on the question of food and agriculture. That’s why I’m particularly encouraged by groups like Rainforest Action Network talking about agribusiness.

Q. How do you think we can help people make the connection between food and nature?

A. Growing your own food or being in touch with the story of your food is one way that we’re going to help people get this connection. Most people don’t really think about food as part of a system, about where comes from, what was the land like that grew it, who were the farmers or farmworkers, what were the conditions for the livestock production. The different facets of the story of our food are still largely invisible to most people. In order to get people to make the food and climate connection, we have to spark our own curiosity about the story of our food. Once you start talking about that story, you see how the story of food connects to everything from the quality of our food to the quality of our water to the quality of our air to what’s happening to the climate.

Q. Are there any food companies that come to mind for you that are doing it right, that are doing their part in trying to reduce their carbon forkprint?

A. Unfortunately, as I was writing the book, I was struck less by really bold, impressive, commendable initiatives coming out of the food industry and more struck by really bold, somewhat perturbed greenwashing methods coming out of the food industry. What I found though—and where a lot of my hope comes from—is a number of really successful people-driven campaigns that have really put the pressure on the food industry to step up and change their practices. You could point to some of the changes those companies have made as examples of companies doing good and going green. But I like to go back to the source of where that change came from. It wasn’t from the company itself; it was from activists on the outside.

I talk in the book about the pressure that college students have been putting on [university] food service companies to go green. They’ve seen some movement happening within some of the biggest food service companies to source more food locally, to think about food waste, and to be more strategic around those kinds of things. The other initiative I mentioned in the book was Rainforest Action Network’s agribusiness campaign, which has actually succeeded in getting companies who have contracts with Cargill for palm oil from Indonesia and Malaysia to essentially tell Cargill they’ll cancel their contracts until Cargill can show they are starting to source more sustainable palm oil.

Q. You talk about spin and greenwashing in the book a great deal, but what does anyone really have to gain from spinning these issues and ignoring the real problem? Is it just about the bottom line? Or do you think it’s ignorance?

A. Often the questions that come up are: “Do you think that these corporate executives know what they are doing? Are they just maliciously doing this to make profit? Do they really know the impact their practices have? Or are they ignorant to these kinds of things?” And I like to say, Look, I don’t pretend that I can get inside the mind of a food company CEO. But if you know anything about how businesses operate, you know that a huge percentage of what a company considers its profits and its profitability comes from brand recognition and what’s called goodwill. You’ll find that companies are willing to spend tens of millions—depending on the size, hundreds of millions—of dollars to protect that goodwill. So greenwashing campaigns that are making you and I feel like these companies are doing something good for the environment, that is an essential part of business operations to maintain that goodwill. So it begs the question: Why is that goodwill so important and why is short-term profitability so important? And that brings us back to the structure of most food companies that are publicly traded. They need to show profitability with every quarterly return. There is an incredible pressure to keep expanding markets, to keep cutting costs, and to keep new customers. Greenwashing is one way to achieve that.

Q. Organic food was all the rage, and now it’s all about local. In terms of the whole locavore movement, what do you see as its importance, and what is the most important thing in your mind, organic or local?

Q. Organic food was all the rage, and now it’s all about local. In terms of the whole locavore movement, what do you see as its importance, and what is the most important thing in your mind, organic or local?

A. Part of the confusion that people might be feeling is this kind of whiplash. First, everybody said it was organic, and now, everybody’s saying it’s local, and what’s a shopper to do? Part of that whiplash was media-constructed in the sense that media loves controversy. To be anti-organic, pro-local is one sort of controversy. But also media loves new trends. Unfortunately for those of us who are advocating for sustainable food, the good, healthy, environmentally friendly food is a pretty old story. But the media doesn’t like that story. They need a new story. So there was a way in which local became the new media darling, and the coverage of it didn’t explain the full concept of local in a way that connected it to the organic movement and to movements that have been around for a long time.

The message about the importance of local often got oversimplified to just be a message of food miles. And the message about food miles got oversimplified to just be about the distance of the farm to your plate. Obviously the food system is much more complicated than that. The reasons we should go local have to do with a whole range of concerns, including the value in having agriculture biodiversity in our country and protecting our green spaces. We know that our agricultural soils are an important place to store carbon. We also know from land use studies and emissions studies what happens when you convert vibrant farmland to a dead strip mall; that has enormous emissions implications. So there’s a multitude of different reasons why local is important, and they add to the story of organic. They aren’t in competition with the story of organic.

Q. Organic food is still pretty pricey; how can we make it more accessible and affordable to low-income people? And how do you think we can get more farmers on board with these sustainable growing practices?

A. I often hear people say, “But Anna, talking about organic food or local food or climate-friendly food—these foods are so elitist; they are so out of reach for most of us.” And I like to stress that the food system that’s truly elitist is our current American food system, which shuts out almost 40 million people who are unsure how they will feed themselves, a food system that makes the worst calories for us, the cheapest and most accessible calories in the supermarket. We really need to call out our current food system for what it is, which is elitist, and argue that what we need to do is really throw our weight behind the kinds of government policies that support food that’s healthier for the planet and healthier for our bodies. Right now the government gives out enormous handouts of our tax dollars just for food, but it’s just not going to food that you and I eat. Most of it’s going to commodities that end up either as high fructose corn syrup or as feed for livestock. So the extent to which we can support policies that help build a greener food infrastructure, those will be policies that help more people access healthy food.

Q. What does your family’s typical diet consist of?

A. My daughter—she’s 9 months—she eats what we eat basically. We eat a very plant-centered diet; occasionally we have sustainable seafood. We really try to support our local farmers market and our local farms as much as possible.

Even though so much of my work is focused on food and what we eat, I found myself a bit overwhelmed thinking about how complicated it’s going to be when I start feeding my daughter solids and how hard it’s going to be to make her food. And I was so glad to have the advice from a friend who is a pediatrician—I wrote the forward to his book called Feeding Baby Green. What he said and what all my other nutritionist friends emphasized to me is that babies are pretty much like you’d imagine them to be: small people. They don’t need to necessarily eat special food. There are a few forbidden foods, but basically your kids can really eat what you eat. But there’s been a deliberate, protracted, very well funded campaign by the food industry over the last 30 years to get us to believe that kids don’t want to eat the food we eat, to get us to believe kids should be fed different food, and that food should be brightly colored, very sweet, and should come in all funny shapes and sizes. There’s been a protracted campaign to get us into buy that myth, so it’s been really liberating for me and my family to to watch our daughter love to eat and love to eat the foods we eat. We basically take most of the meals we cook for ourselves, throw it in a food processor to make it easy for her to chew, and feed it to her. She’s a great eater.

Q. What do you see as a real sign of a cleaner, greener world that’s happening right now?

A. One of the big things I’m really hopeful about is the growing movement of people in cities connecting to local farms, growing their own food. Again, this is because of where I live in a city and who I’m connected to, but there are initiatives, projects around connecting community to food popping up across the country. You can see it in projects like Brooklyn Grange, and in the reports we hear from some of the seed sellers that they’ve run out of supply of certain seeds because there’s been such a run by urban gardeners, community gardeners, and kitchen gardeners around the country.