Trucks carry loads of bitumen-laced sand through an open-pit mine.Photo: Jonathan HiskesOver the past few days I flew over the devastated landscape of the Alberta tar sands, toured the nearby boomtown struggling to deal with the influx of mining workers, scoffed at greenwashing by the energy companies, and snuck a nugget of hardened bitumen home as a souvenir.

Trucks carry loads of bitumen-laced sand through an open-pit mine.Photo: Jonathan HiskesOver the past few days I flew over the devastated landscape of the Alberta tar sands, toured the nearby boomtown struggling to deal with the influx of mining workers, scoffed at greenwashing by the energy companies, and snuck a nugget of hardened bitumen home as a souvenir.

What I didn’t find in the Canadian subarctic were any solutions for “fixing” the tar sands. The solutions are down the pipelines in the U.S., where most tar-sands oil ends up (the U.S. imports more oil from Canada than from any other country). As with the BP Gulf spill, the most promising responses are the ones that shrink the demand for oil — efficient vehicles, electric vehicles, cities and towns designed to let people get around without driving.

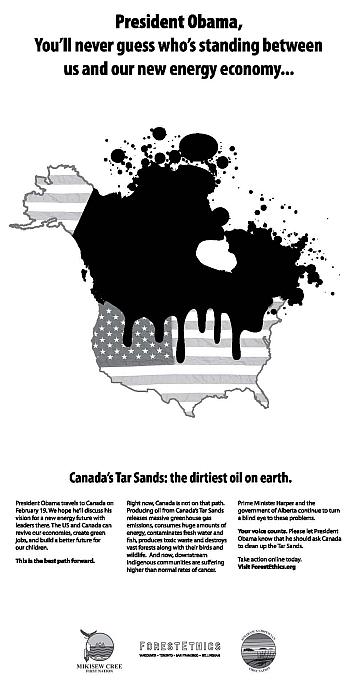

February 2009 USA Today ad (click for larger version).So it’s surprising that one of the environmental groups most active in the tar sands, ForestEthics, isn’t trying to reduce the need for oil (disclosure: they paid for most of my trip). Instead, the group is trying to make the tar sands a liability for major American corporations, threatening to run public campaigns against companies that use tar-sands oil to ship their goods. It ran a full-page ad in USA Today with Canadian oil dripping onto an American flag, showing companies how it could mess with their logos in a public campaign.

February 2009 USA Today ad (click for larger version).So it’s surprising that one of the environmental groups most active in the tar sands, ForestEthics, isn’t trying to reduce the need for oil (disclosure: they paid for most of my trip). Instead, the group is trying to make the tar sands a liability for major American corporations, threatening to run public campaigns against companies that use tar-sands oil to ship their goods. It ran a full-page ad in USA Today with Canadian oil dripping onto an American flag, showing companies how it could mess with their logos in a public campaign.

This year ForestEthics petitioned 30 companies to explain the high environmental and social costs of tar-sands oil (which carries three to five time the greenhouse-gas footprint of conventional drilling). The group persuaded 16 of them to boycott shipping companies that use tar-sands oil, or to at least give preference to ones that don’t, U.S. campaign director Aaron Sanger told me. They include Walgreens, Timberland, The Gap, Levi Strauss, Bed Bath & Beyond, and several that haven’t yet announced their shift.

“We found that it was a relatively simple process of surveying our vendors, seeing which ones may have tar sands oil sourcing and simply avoiding those vendors,” a Walgreens spokesperson said in a story widely distributed in the Canadian press in August. “We are in that process right now.”

Enlisting well-known companies to speak out against tar-sands oil, Sanger said, helps create political momentum for policies that promote alternative energy. That’s the connection to reducing our dependence on oil. “That [political progress] is the only point of our work,” ForestEthics Executive Director Todd Paglia told me.

The group ran a similar successful campaign against Victoria’s Secret (Limited Brands) several years ago to get it to use more responsibly sourced paper products for its catalogs. But in most cases, said Sanger, education plus the threat of a campaign is enough to persuade companies.

“For all the power of [public-facing] corporations, that power hangs by a thread, which is their brand,” he said.

He’s also found that corporations have officers of sustainability or social responsibility, often at the vice-president level, who increasingly have power to make substantive changes. Persuading them, he says, is far easier than reaching 300 million Americans.

Energy companies have responded by seeking new ways to ship tar-sands oil out of North America — they’re seeking to build the Keystone XL pipeline to refineries on the Gulf coast and the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline to the coast of upper British Columbia. North American groups like ForestEthics have less leverage over fuel-buyers in Asia, so they’re fighting those proposals.

But if companies are forgoing tar-sands crude, aren’t they just buying more oil from the Gulf of Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Russia, and other places with their own problems? Sanger argued that the tar sands have two distinct problems.

First, while offshore drilling is prone to disastrous accidents, tar-sands mining inflicts significant damage even when things go right. (Three million gallons of toxic waste water leak into the Athabasca River each day by design, flowing toward First Nations communities, according to industry records analyzed by the Pembina Institute.)

Second, the tar sands give us a preview of just how difficult it will become to retrieve oil as global appetites burn up the most accessible reserves. Recovering oil-sands bitumen requires both large amounts of natural gas, which could be used instead to heat homes, and two to four barrels of water per barrel of oil. The endeavor is a poster child for the age of “difficult oil.”

Sanger believes in focusing on the tar sands because “it shows the extreme consequences of this form of energy. And it shows them up front, close and personal, right across the border.”

When I talk to friends and extended family who don’t track this stuff too closely, I get the sense that they don’t need more evidence that fossil fuels are problematic. They need evidence that we have decent alternatives. But, as investment in tar-sands mining grows (it reached $20 billion in 2008), its destructive nature is going to come into even sharper focus. We’ll be hearing more about it.