Incumbent Gov. Ted Strickland (D) has taken modest but meaningful steps to green one of the most industrialized states in the country. The alternative-energy standard he signed into law in 2008 has ramped up demand for wind and solar components and even more demand for tools to cut energy waste — high-efficiency light bulbs, HVAC systems, windows, and insulation — all of which can be manufactured in Ohio. He directed federal stimulus funds to retrofit factories to capture and reuse waste heat, a potentially huge energy source. His work helped position the state as a leader in weatherizing homes and industrial plants.

Incumbent Gov. Ted Strickland (D) has taken modest but meaningful steps to green one of the most industrialized states in the country. The alternative-energy standard he signed into law in 2008 has ramped up demand for wind and solar components and even more demand for tools to cut energy waste — high-efficiency light bulbs, HVAC systems, windows, and insulation — all of which can be manufactured in Ohio. He directed federal stimulus funds to retrofit factories to capture and reuse waste heat, a potentially huge energy source. His work helped position the state as a leader in weatherizing homes and industrial plants.

Republican challenger John Kasich, in contrast, makes no mention of energy on his website or in stump speeches and never broaches the subject of climate change. His broader economic plan involves eliminating the state’s income tax — which pulls in 45 percent of its revenue — without spelling out how he would slash the budget to make that possible. He’s marketing himself as an “outsider” — despite the fact that he’s a former U.S. representative, Lehman Brothers executive, and guest host for Sean Hannity and Bill O’Reilly of Fox News, meaning he’s spent time at three of the most powerful political, financial, and media institutions in the world. He’s got an eight-point lead, according to recent polls, so he doesn’t appear to be paying a price for staying silent about energy issues and budget specifics.

Unemployment is the big issue in the state this year, as it is everywhere. Ohio’s unemployment rate in August was 10.1 percent. The state has seen some positive movement with green jobs; last year, Ohio led the nation in green-job growth stimulated by the federal Recovery Act, with an estimated 2,500 new jobs created. And the state’s 2008 alternative-energy standard, which also requires big improvements in energy efficiency, is expected to create about two years of work for some 1,700 people, plus additional jobs in related industries, according to a new report from the advocacy group Policy Matters Ohio.

But Strickland hasn’t been talking up the economic benefits of his clean-energy efforts, so most voters haven’t noticed. “I don’t think the average Ohioan feels that or sees it,” said Jennifer Miller of the Ohio Sierra Club. Efficiency is devilishly difficult to visualize — since it’s the act of electricity and heat not being wasted. Since it happens at homes, businesses, and factories across the state, there is no central landmark. And weatherizing jobs come in small batches — say, a firm expanding from four to 10 workers — so it doesn’t garner the headlines of an auto plan adding hiring 500 workers at once.

The green-ish issue that has gotten attention is the proposed “3-C” rail line that would connect Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati. It would be a key first step in building up the state’s meager transit network, and Strickland worked to secure $400 million in federal stimulus funding for it. Kasich calls it “one of the dumbest ideas” he’s ever heard and vows to block it if elected. He criticizes it with the deceptive argument that trains would travel the 265-mile route at an “average” of 39 mph, but that’s only if you count time for stops and don’t consider express trains that make few stops.

Kasich says he’d use the funds for roads instead, but that’s a “false option,” according to Amanda Woodrum, a transportation specialist at Policy Matters Ohio. “Either we build this or we turn that money away,” she said.

Ohio has always lagged in public transportation, which makes it difficult for residents to even imagine a system that could be truly useful, says Woodrum. It’s the seventh most populous state, but it ranks 40th in transit spending. Recent funding troubles have forced service cuts in Cleveland and elsewhere.

“We’ve made progress in moving toward a clean economy, but that strategy hasn’t really translated into our transportation sector,” she said. “It really makes it impossible to get by without cars.”

Strickland has had limited success in pushing transit projects through the state’s Republican-controlled Senate, but the progress on the 3-C route suggests he would keep working at it, according to Miller of the Sierra Club. “He understands the social justice angle of why we need public transit, and the jobs angle, and the environmental benefits,” she said.

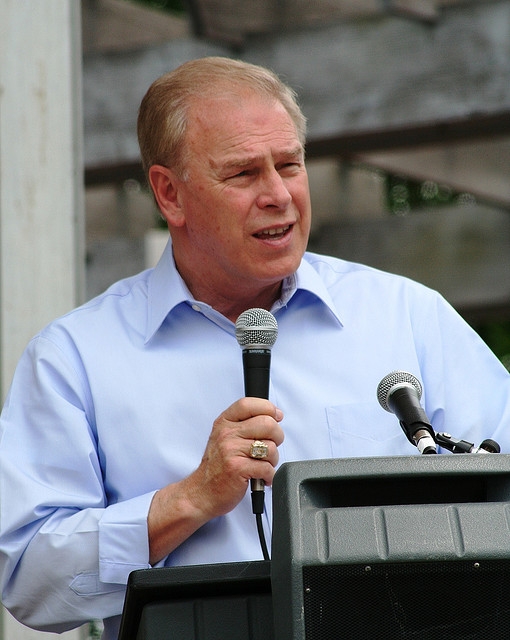

Ted Strickland

StricklandPhoto: OZinOHDespite the steps he’s taken to green Ohio’s economy, Strickland took a position against national progress earlier this year when he asked the U.S. EPA not to regulate greenhouse-gas pollution out of “deep concerns” for Ohio’s economy. He said [PDF] he did “not dispute the need to address climate change,” though EPA action is the only likely national plan in the near future.

StricklandPhoto: OZinOHDespite the steps he’s taken to green Ohio’s economy, Strickland took a position against national progress earlier this year when he asked the U.S. EPA not to regulate greenhouse-gas pollution out of “deep concerns” for Ohio’s economy. He said [PDF] he did “not dispute the need to address climate change,” though EPA action is the only likely national plan in the near future.

Strickland grew up in a poor coal-country town in southern Ohio and has been a supporter of coal — Ohio has the seventh largest recoverable coal reserves in the U.S., and gets 88 percent of its electricity from coal.

He backed plans for a new coal-fired power plant (which was eventually cancelled), and steered $150 million from a 2008 state stimulus package toward advanced energy research, which included the unproven “clean coal” concept as well as solar and wind.

On his campaign website, Strickland focuses on “developing advanced energy.” But attorney Nolan Moser of the Ohio Environmental Council says the governor has pushed an “all of the above” energy approach. “He wants projects moving forward in Ohio, no matter what they are, as long as they’re creating jobs,” he said. “We disagreed with him on coal.”

Like Kasich, Strickland spent time in Congress, representing Ohio’s 6th District for six terms. He earned a 77 approval rating from the League of Conservation Voters during that time. “Ohio isn’t exactly a green state, so he’s got a strong record in that context,” Bill Demora of the Ohio LCV told Grist in 2006. “We’re very proud to back him.”

John Kasich

KasichIn a 1999 speech to the National Environmental Policy Instit

KasichIn a 1999 speech to the National Environmental Policy Instit

ute, then-Congressman Kasich said, “Stewardship of the environment is nothing less than a moral obligation — because God made it and gave it to us to properly manage. It will be part of the bequest we make to our children and grandchildren.”

He also attacked “we can’t afford clean air” arguments: “We have behaved as if protecting the environment was somehow at odds with the economic growth and prosperity that also are so important to us. This is a false and dangerous dichotomy; it forces unnecessary divisions,” he said.

But in this current campaign, he’s said nothing about the importance of protecting the environment. He hasn’t spoken against Gov. Strickland’s clean-energy work, but neither has he signaled support.

“I haven’t seen much from the campaign that suggests it’s going to be a priority,” said Moser. “We don’t know too much about Congressman Kasich’s views on energy issues. For whatever reason, he has chosen not to make that a campaign plank.”

——-

Note: Some of the comments below pre-date this story, since we launched our Gubernatorial Tutorial series before publishing this article. Let the conversation continue!