This story was written by Shanti Menon.

This story was written by Shanti Menon.

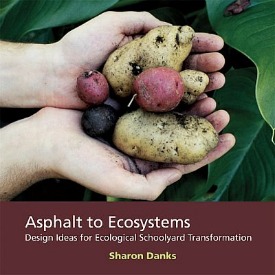

In her new book Asphalt to Ecosystems: Design Ideas for Schoolyard Transformation, Berkeley-based environmental planner Sharon Danks explores the ways in which landscape design, architecture, child development, and nutrition converge in the schoolyard. OnEarth sat down with Danks, whose firm, Bay Tree Designs, Inc, is helping redevelop some 29 San Francisco schoolyards, to talk about how communities are transforming the asphalt playgrounds of the past into green spaces conducive to better learning, eating, and playing.

Q. How have playgrounds changed since we were kids?

A. Playgrounds these days are influenced largely by liability concerns. Swings are disappearing, bars are getting lower, structures are becoming less challenging.

My 4-year-old recently broke her arm on a play structure meant for 2 to 5-year-olds because she found it so boring. She was walking on the outside of the bridge and sliding down the handrail and fell off. These structures are so unchallenging that kids are making up their own activities, which are often 10 times more dangerous.

Q. What’s your vision of a better playground?

A. We want to give kids something more than play structures and ball games. We call them “ecological schoolyards,” environments that combine diverse ecosystems with varied play environments and hands-on learning experiences. Richard Louv, the author of Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder, says that playgrounds based on ballgames and athleticism are home to more bullying. In more natural environments, it’s less about who’s the strongest and the fastest and more about using the imagination. It changes the dynamic of who’s in charge. And there’s less conflict because the kids aren’t as bored.

The Perkins Elementary School before and after its makeover by the Boston Schoolyard Initiative. Photo: Boston Schoolyard Initiative with permission.

The Perkins Elementary School before and after its makeover by the Boston Schoolyard Initiative. Photo: Boston Schoolyard Initiative with permission.

Q. How can kids learn from playgrounds?

A. You can embed a curriculum into the landscape by allowing students to see natural systems as they function. So instead of studying a watershed in a book, for example, they can see rainwater falling off their roof into a pond. Most students would shrug if you asked them when it last rained, but here they can run to the window and see how dry the pond looks.

Q. Can the schoolyard help replace the nature that’s vanishing from most of our lives?

A. I read an article that chronicled how far each generation of kids in a single family ventured from their home to play. As an 8-year-old, the grandfather roamed four to six miles to go fishing. The father wandered about two miles from home, and the son about half a mile. Our kids are lucky if they walk to the end of the block. In many cases, school grounds are their only exposure to outdoor play, and if all they have is asphalt and some liability-engineered version of climbing, I’d say they’re missing out.

Q. Tell me about the work you’re doing for public schools in San Francisco.

A. We work with the teachers and parents, and sometimes the students, to do collaborative brainstorming and design that results in long-term plans to transform each school’s grounds. We help gather the communities around the projects and make sure the plans reflect their educational and recreational needs. Hands-on involvement builds a sense of ownership and also gives communities more bang for their buck.

Q. What are some of the changes you expect to see?

A. Many schools are putting in play environments with boulders and logs for kids to explore. There are ponds going in, some with solar-powered pumps. Others are experimenting with pollinator gardens, with native plants to attract butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds. And almost every school is changing the standard seating arrangement of benches in a row — designed for passive observation — and moving toward cluster seating, so classes can engage in interactive teaching and conversation.

Q. What sort of long-term effect do you think this playground renovation will have?

A. I see these schoolyards as models of ecological design for our cities. If a school treats water responsibly, produces some of its own energy, has space for wildlife habitat, and makes some of its own food, kids understand from an early age how these things work and learn to value them. That makes for more informed, responsible citizens.

Q. You mention in the book that ecological schoolyards send a positive message about the environment.

A. Kids are often asked to save the environment before they’ve learned to love it. It puts a sense of fear into them: The polar bears are going to die, and you’re 5 years old, so what are you going to do about it? A schoolyard is empowering. Flowers are blooming where there was once lifeless space, more birds are coming, there’s less flooding when it rains. They can see their actions translating into improvement.

Q. What are some of the coolest schoolyards you’ve seen?

A. There’s a school in Berlin that used to be entirely paved, and they put in a dry creek bed that fills when it rains, with a hand pump and a sandpit. I saw 15 kids working together to dam a puddle, and at the end of recess, with great excitement, they opened the dam and let the water flow into the creek. And there’s a guy in Norway who builds Tarzan play environments involving telephone poles with metal bars set on valleys of stacked tires. Kids swing across the chasm on rope swings to the other side, and the swings are set so they can bump into each other. Here we think it’s too dangerous for swings to interact that way, but no one there seems to be getting hurt.

Q. This stuff is big in Europe and in California, but will it ever fly elsewhere in the States?

A. There are thousands of American schools doing habitat and garden projects. There’s a Boston Schoolyard Initiative, and groups in Fort Worth, Portland, Boulder, and Chicago. At Sidwell Friends, in Washington, D.C., where President Obama’s kids go, they have a blackwater [sewage] treatment wetland right at the front entrance. You walk through that to get into the school. So we’ve come a long way.

Q. How can I get my kids’ school started on a project like this?

A. The first thing is to get a committee of parents and teachers together and make sure the principal is open to the idea. Engage people, show them what’s possible, and then start to envision. Evergreen, in Canada, puts out a publication called “All Hands in the Dirt,” which includes a step-by-step process for designing schoolyards. Divide your plan into priorities and do one project at a time. Maybe you start with an edible garden and then turn it into a wildlife habitat, so you pull out the edibles and put in native plants. That way you continue to engage the community, and you make it sustainable financially, so you don’t have to raise a huge amount of money at once.

Learn more about green schoolyards:

This article was syndicated with permission from OnEarth.