This story was originally published by The Conversation and is reproduced with permission. You can find the original article here.

As nations gear up for a critical year for climate negotiations, it’s become increasingly clear that success may hinge on one question: How soon will China end its reliance on coal and its financing of overseas coal-fired power plants?

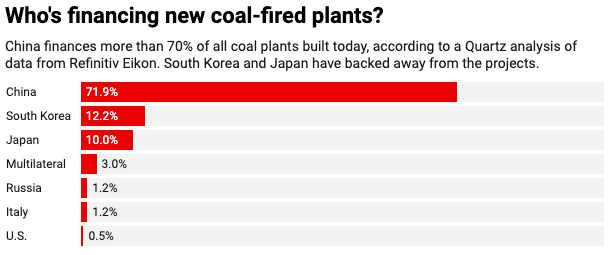

China represents more than a quarter of all global carbon emissions, and it has spent tens of billions of dollars to build coal power facilities in 152 countries over the past decade through its Belt and Road Initiative. Roughly 70% of the coal plants built globally now rely on Chinese funding.

That’s a problem for the climate. The International Energy Agency warns in a new analysis that if the world hopes to reach net zero emissions by 2050, widely seen as necessary to meet the Paris climate agreement goals, there should be no investment in new fossil fuel supply projects or in new coal-fired power plants that don’t capture their carbon emissions. Shortly after that report came out, the G7 group of leading industrialized democracies called for an end to international financing of unabated coal projects on May 21, 2021.

U.S. presidential special climate envoy John Kerry was asked pointedly about China’s progress on climate change when he testified before the House Foreign Affairs Committee in mid-May.

Chinese President Xi Jinping had called climate change a “crisis” during a world leaders’ summit on climate change a few weeks earlier, but Kerry said talks between the two countries grew “very heated” over China’s continued insistence on financing coal-fired power plants around the world.

While he stopped short of saying it explicitly, Kerry made the U.S. position clear: China’s climate pledges won’t be credible or legitimate until it stops overseas coal financing. “We’ve got five more months left to get them to embrace something we hope you will view as legitimate,” he said. “We’re not there yet.”

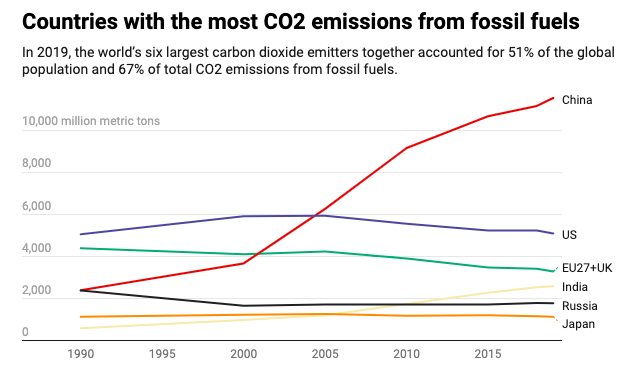

China and the United States together represent 43% of global carbon dioxide emissions. They worked together to make the Paris Agreement happen. They will have to push each other to make it a success.

Closing some coal at home, but building overseas

China has been the world’s largest carbon emitter for 20 years. It’s been responsible for 28% of the world’s carbon emissions for the past decade. That number hasn’t budged, despite rapid growth of China’s renewable energy and clean tech industries.

One of the central reasons is coal, the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel. Coal accounted for 58% of China’s total primary energy consumption as recently as 2019 – even as coal use was collapsing elsewhere. China currently operates 1,058 coal plants, roughly half of all coal plants worldwide. To meet even its modest climate goals, it will have to shut down more than half of them, according to a recent analysis by TransitionZero, a U.S.-based thinktank.

But will it?

China has incentive to cut emissions. With air pollution choking some of its largest cities, it has shuttered dozens of old coal facilities in recent years, and has subsidized renewable energy projects, both domestically and globally.

But despite this progress, China is still building new coal plants.

It has also made a strategic decision to export its industrial and manufacturing might across the globe under its Belt and Road Initiative. Japan and South Korea, which traditionally financed overseas coal projects, have started to abandon them, and China sees opportunity. Nearly all of the 60 new coal plants planned across Eurasia, South America and Africa –70 gigawatts of coal power in all – are financed almost exclusively by Chinese banks.

It’s clear that China is juggling energy security and economic growth concerns. That’s why analysts were surprised when Xi announced in late 2020 that China would be carbon neutral by 2060, a decade earlier than planned, and make sure its carbon emissions peaked before 2030.

Such an effort would require huge investments in renewable energy, electric cars and technology like carbon capture and storage. None of this will be easy for China. The country has made little progress on reducing emissions, according to recent reports from organizations including the International Energy Agency.

US-China talks

Seasoned climate negotiators are watching what China does with coal today – not just the pledges it makes that are 10 or even 20 years in the future.

The U.S.-China climate relationship was central to reaching the Paris climate agreement, Todd Stern, former U.S. climate negotiator, has said. Failure to revive such engagement “would have grave national security consequences in the United States and around the world.”

Shortly before the recent world leaders’ summit on climate change, the United States and China agreed to work together again on the climate issue, and U.S. President Joe Biden announced ambitious new climate plans

But talk isn’t action. The world will expect both to commit to measurable actions ahead of the United Nations climate summit in November. Countries are expected to strengthen their pledges this year – hopefully enough to keep global warming in check.

I worked in both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations and have been involved in climate change issues for several years. It’s clear that if China and the U.S. don’t lead the way, the world won’t get on track to meet the Paris climate goals.

China has reason to cooperate on climate change

China is already planning for a world in which fundamental natural resources like water and food grow scarce because of climate change. For example, when China saw a looming threat to its ability to grow enough soybeans, due in part to climate change, it went from importing virtually no soybeans to importing more than half the soybeans sold on Earth. I outline the reasons for this tectonic shift in my book “This is the Way the World Ends.”

China also sees economic opportunity in solving the climate crisis. It is mining raw materials essential to battery storage solutions at the heart of a global renewable energy industry; building cheap electric vehicles as fast as it can for domestic and foreign consumers; and aggressively subsidizing solar panel manufacturing and exporting those panels worldwide.

China lost the tech revolution race that defined the global economy of the 20th century. It does not intend to lose the renewable energy and clean tech revolution that will define the 21st.

But even that imperative has not kept China from financing the world’s reliance on coal-fired power. Which is why climate negotiators hope China does more than make promises for the future. Ending coal financing overseas would be a serious first step in that direction.