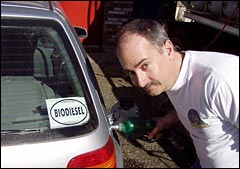

Dan Freeman.

As a kid, Dan Freeman experimented with using alcohol to run lawnmowers and minibikes. (Oh, to have been a fly on the wall for that parent-son conversation.) These days, he runs Dr. Dan’s Alternative Fuel Werks, a Seattle-based biodiesel retail and distribution company with customers ranging from school districts to organic farmers to concerned individuals who want to drive greener.

Grist recently spoke to the good doctor — who got his nickname years ago from his father, an underemployed Ph.D. at the time — about waste reduction, the power of local energy sources, and why biofuels are like organic food. Eat your heart out, McDreamy.

How did you first get involved in biofuels?

During the ’90s, I had a friend who worked for the local gas utility, and he told me about natural-gas vehicles. I saw an opportunity to make a difference and make a living at the same time. I was apparently mistaken about that [laughs], but it got me involved in doing natural-gas conversions. And then I became a member of the Puget Sound Clean Cities Coalition, and they tried to talk me into biodiesel.

At first, I said no stinking way. I thought it was another thing that would perpetuate diesel, and since the diesel engine manufacturers were notorious for pointing fingers at each other and not doing anything to develop cleaner, more efficient engines and cleaner fuels, I wanted nothing to do with them. But Puget Sound Clean Cities was persistent and arranged a meeting with the Washington State Ferries. Washington State Ferries at the time was all for it. It was a way that they could lower their emissions and lower their operating costs. And I started selling biodiesel.

What changed your mind about biodiesel then?

We’ve got dire problems, and we’ve got to do something right away. It’s like planning for our retirement — how well have we done that? Here’s something that we can do immediately and it’s cheap and practical. It just makes sense.

What do you use for feedstock?

All our fuel is currently from virgin soy. We get it from a farmer-owned co-op in Iowa. It’s our big goal to have Washington-state grown, produced, and used biofuel. We very much want to emulate the organic food movement. It doesn’t make sense to transport energy over long distances. It takes a lot of energy to do that.

What kind of car do you drive?

I bought my first new car ever. It’s a 2004 Volkswagen Golf TDI. So far the best mileage I’ve gotten is 47 miles per gallon.

So what do you think are people’s biggest misconceptions about biodiesel?

“What do I have to do to my car to convert my car to biodiesel?” You don’t have to do anything to a diesel car. The car just has to be in good operating condition. And there’s lots of people going, “Oh, well, biodiesel consumes more energy to grow and produce than you get out of it,” and that’s not true.

In your opinion, what do you see as the future of biodiesel?

I’d change the question a little bit to, “What do I see as the future of biofuels?” Biodiesel is a great solution, but not the only solution. Biofuels in general would be a tremendous boon for the United States — and for Washington state to have locally grown, produced, and consumed fuel. Right now all the money for fuel leaves the state.

We need long-term, sustainable solutions. Biofuels should be made from agricultural byproducts. We’re paying farmers not to farm, so they can certainly grow some biofuel feedstock. People say we can’t go on with soybeans, and that’s true — we can’t and we shouldn’t. But through proper farming practices, such as crop rotation, agricultural byproducts, and utilizing our waste streams, we can dramatically reduce our dependence on foreign oil, clean up the environment, and enrich our economy.

So it sounds like you’re arguing for efficiency, basically.

Yeah, a few hundred years ago we used 100 percent of whatever it was we had. If you killed an animal, you used every part of that animal. If you cut down a tree, you used every part of that tree. Nothing went to waste. And now we’re throwing away our resources, and I don’t really think that we can afford to do that.