Climate Wire (subs. req’d) reports today:

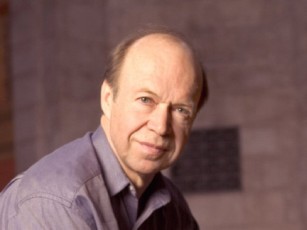

NASA’s leading climate scientist says he hopes that climate legislation proposed by Democratic Reps. Henry Waxman (CA) and Edward Markey (MA) to introduce carbon emissions trading to the United States fails. He says lawmakers should abandon cap-and-trade initiatives altogether and implement a simple carbon tax instead….

“Trading of rights to pollute … introduces speculation and makes millionaires on Wall Street,” Hansen said in his keynote lecture at Columbia University’s 350 Climate Conference held here Saturday. “I hope cap and trade doesn’t pass, because we need a much more effective approach.”

Hansen also stands opposed to so-called “cap and dividend” proposals that would introduce pollution trading and a near full auctioning of emissions, with proceeds from the auctions going back to the public. Instead, Hansen proposed a “tax and dividend” approach to tax fossil fuels at the point where they are extracted from the ground, to set a firm price on carbon. Proceeds from the tax, rather than from the auctioning of allowances, would then be distributed to consumers.

“It could be implemented in one year, as opposed to decades with cap and trade,” he said. “The bureaucracy is very simple.”

Why oh why do even smart people like NASA’s James Hansen think that there is such a thing as a “simple carbon tax”? Have you folks ever looked at the friggin’ tax code?

Seriously, nothing bugs me more than this notion that Congress would ever pass a “simple” carbon tax, even if it were politically feasible, which it most certainly is not. Well, one thing bugs me more — people who attack the first serious chance we have to get major energy and climate legislation because they are operating under the severe misimpression that the political system of this country might embrace a tax.

Nobelist Al Gore, who also embraces a 350 ppm target like Hansen, combines political realism with his climate science realism, which is why he takes the exact opposite view that Hansen does — see Gore on Waxman-Markey: “One of the most important pieces of legislation ever introduced in the Congress … has the moral significance” of 1960s civil rights legislation and Marshall Plan.

Let’s be very clear here, since there are obviously a great many smart people who keep pushing a carbon tax instead of cap-and-trade, who are wasting a lot of time tilting at windmills, so to speak, when they should be building them instead (with the help of Waxman-Markey):

- A carbon tax, particularly one capable of deep emissions reductions quickly, is a political dead end. Neither the Obama administration nor senior members of Congress support a carbon tax. Quite the reverse. Obama (and Clinton and Biden) campaigned on a cap-and-trade system. That is the only game in town. Now you can choose to play checkers when everyone else is playing chess, but don’t be surprised if everyone else starts to criticize or ignore you.

- A carbon tax that could pass Congress would not be simple. Advocates of a tax argue that simplicity is one of its biggest benefits. Again, those advocates seem bizarrely unfamiliar with the tax code in spite of the fact that they pay taxes every year. And those advocates seem unfamiliar with what happened the last time Congress tried an energy tax. Does anyone think a carbon tax could be enacted into law that did not have various exemptions or that did not allow companies to pay part of that tax by purchasing offsets? Get real, people. Again, we ain’t playing checkers here. The Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill isn’t complicated because its authors want a complicated system. It is complicated because this is a complicated issue and various powerful interests get to weigh in and influence the outcome to protect their interests. The same would be true of a carbon tax bill.

- A carbon tax is woefully inadequate and incomplete as a climate strategy. Why? Well, for one, it doesn’t have mandatory targets and timetables. Thus it doesn’t guarantee specific emissions results and thus doesn’t guarantee specific climate benefits. Perhaps more important, it doesn’t allow us to join the other nations of the world in setting science-based targets and timetables. Also, a tax lacks all of the key complementary measures — many of which are in Waxman-Markey — that are essential to any rational climate policy, but which inherently complicate any comprehensive energy and climate bill. Also, the notion that you could return all the money of a tax back to the public is rather naïve at best and counterproductive at worst.

Let me elaborate on these points.

1. A carbon tax, particularly one capable of deep emissions reductions quickly, is a political dead end. There simply aren’t any major politicians — in office – who support one. So I’m not certain who is going to introduce this imaginary “simple carbon tax” as a bill, and I’m quite certain very few are going to vote for it. The Obama administration campaigned on a cap-and-trade, and they are the only ones who can change the direction of US climate policy, the only ones who could move us to a tax. Since they aren’t going to do that, it is a monumental waste of everyone’s time for people like Hansen to rail against cap-and-trade. You might as well howl at the moon or look for gold at the end of the rainbow.

The weird thing to me is not that Hansen refuses to combine policy/political realism with climate science realism. He is, after all, a climate scientist — the one I admire most greatly (see “American Meteorological Society gives James Hansen its top honor“) — and not a politician. The weird thing to me is that Hansen refuses to be internally consistent and advocate policies that match his scientific statements. I have blogged on this at great length here: “An open letter to James Hansen on the real truth about stabilizing at 350 ppm.”

Let me repeat the key point: It is utterly inconceivable that you could stabilize atmospheric concentrations anywhere near 350 ppm by using a carbon price as your primary mechanism.

A price isn’t what is needed to stop building any new coal plants and shut down every existing one in 10 years in rich countries and 20 years everywhere else — and replace all that power (plus growth) with carbon-free generation and efficiency. Plus you have to build all the necessary transmission.

Indeed, I can’t imagine how high a price would be needed but it is probably of the order of $1000 a ton of carbon or more starting in 2010. Talk about shock and awe. Remember, we are talking about a carbon price so high that it actually renders coal plants that have been completely paid for uneconomic to run. And once you stop new demand and start shutting down existing plants, the price of coal will collapse to almost nothing.

Once you start building all of the alternatives at this unimaginable pace, bottlenecks in production and material supply will run up their costs. The collapse in coal prices, making existing plants very cheap to run, together with the run up in the price of all alternatives will force carbon prices even higher.

But, in any case, if you want to replace all those existing coal plants with carbon free power that fast, again the carbon price is almost beside the point. How are you going to site and build all the alternative plants that fast? How are you going to site and build all the power lines that quickly? How are you going to allocate the steel, cement, turbines, etc? How are you going to train all the people needed to do all this?

There is only one way. That is a WWII-style and WWII-scale government-led mobilization. As Hansen and his coathors conclude in their landmark paper (see “Stabilize at 350 ppm or risk ice-free planet, warn NASA, Yale, Sheffield, Versailles, Boston et al“):

The most difficult task, phase-out over the next 20-25 years of coal use that does not capture CO2, is Herculean, yet feasible when compared with the efforts that went into World War II.

Well, we didn’t accomplish the WWII mobilization through a pricing mechanism. So if you support 350 ppm — and as readers know, I have various issues with that target — then you need to be honest with the public about what the right policy approach is and not go about A) offering policy proposals that won’t get you 350 and B) criticizing others who may not embrace your target for advancing a different approach that also won’t achieve 350 ppm.

2. A carbon tax that could pass Congress would not be simple. I would have thought this was obvious were it not for the large number of very smart people who believe otherwise. Again, look at the U.S. tax code. Let’s also look at what happened with the BTU tax. There were granted:

… a steady string of energy-tax exemptions to key lawmakers, special pleaders and important industries. Farmers won exemptions on diesel fuel for tractors. Majority Leader George Mitchell won an exemption for home heating oil, an important commodity in New England. Clinton himself agreed in an April telephone call (from a Congressman at a pay phone in Oklahoma) to change the way the tax would be collected on natural gas, electricity and oil.

And as for rip-offsets, strong political forces are insisting upon a cap-and-trade system that includes large amounts of offsets to substitute for a fraction of the emissions permits/allowances that carbon-emitters need to buy. I am not a fan of rip-offsets (see “The one simple change that could vastly improve Waxman-Markey: Sunset the rip-offsets“) — although they are not as bad as many people think, as I will discuss in later posts.

But why wouldn’t those same strong political forces insist that carbon-emitters be able to pay some of their carbon tax through the purchase of offsets? It would be very “simple” to introduce that into this imaginary carbon tax bill. But it would create a bureaucracy comparable to the one needed for Waxman-Markey.

It’s the golden rule, folks. If you have the gold — in this case, the lucre from selling unsustainable, polluting energy — you get to write some of the rules.

And if Hansen thinks that it would be politically possible to raise carbon prices that high without diverting some of the money to affected industries, again, I’m not certain what country he is living in.

And again a carbon price isn’t going to solve the problem by itself. You need a bunch of complementary measures that complicate the legislation. I have been meaning to write about a recent Carnegie Mellon University report that came to that exact conclusion, but until I get around to that, you can look at the Green Car Congress piece on it, “CMU Paper: Market-Based Mechanisms for CO2 Reduction Will Be Insufficient to Attain Mid-Century Goals.”

Hansen sort of acknowledges this:

But ultimately, an effective response to climate change will require a variety of actions, he argued. That includes a new, much stronger international agreement, action by U.S. lawmakers to finally put a price on carbon through a tax, and new policies designed to ultimately phase out fossil fuel consumption.

“We’re going to have to make the decision to leave coal in the ground” or burn it only at power plants utilizing carbon capture and sequestration technology, Hansen said. “Perhaps the best chance is in the courts,” he added.

Courts? Yeah, that’ll get it done in the time frame needed.

Fine, “we need new policies designed to ultimately phase out fossil fuel consumption.” Waxman-Markey isn’t perfect, but it has some of those policies and it’s a start.

3. A carbon tax is woefully inadequate and incomplete as a climate strategy. Let me just focus on one issue here — the need for targets and timetables. A climate bill must have binding targets and timetables if it is to achieve any desired emissions or concentration goal. That is especially true because we need to have a credible piece of legislation to convince the rest of the world that we are serious about emissions reduction.

Thus the “simple carbon tax” bill would have to have binding, specified targets and timetables similar to (if not stronger than) Waxman-Markey. It would have to have some sort of mechanism for constantly adjusting the tax to make sure emissions goals were being met. The obvious mechanism is to simply auction the permits and let the market decide what the price is. Otherwise, you have to develop an equally complicated bureaucracy that keeps changing the carbon price based on past performance and that keeps trying to guess what future price is needed to achieve the binding targets and timetables.

So again, whatever this carbon tax bill would be — at the end of the day it would probably look a lot like a cap-and-trade system with exceptions and allocations for certain industries, international and domestic offsets, various complementary measures like energy efficiency standards, and some complicated oversight board but constantly adjusted the price.

I can appreciate Hansen’s frustration with the politics and bureaucracy surrounding a cap-and-trade. But I think that is far more an inevitable outcome of the nature of this legislation and the nature of our political process than it is inherent in the policy measure. And the notion that the political system would somehow accept a much higher price of carbon through a tax bill but not a cap-and-trade bill is, again, naive.

The Climate Wire story notes:

Public remains apathetic about climate Hansen also said climate activists need to be more vocal and strategic in getting the public to lobby harder for action to reduce emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. He pointed to recent public opinion polls showing that among Americans’ concerns, climate change ranks nearly last in the order of priority, well behind the economy and the United States’ dependence on foreign oil.

“It’s hard for people to realize that we have a crisis, because you don’t see much happening,” he said. “If people understood the implications for their children and grandchildren, they would care.”

Well, again, a surefire way to make sure that you don’t see much happening is to keep campaigning against Waxman-Markey, because that is the only serious comprehensive energy and climate legislation around.

Hansen also urged conference participants to press the United States to negotiate a robust international agreement by the final negotiating round of U.N. climate change talks this year at Copenhagen. He said the new agreement has to be much more far reaching than the Kyoto Protocol, which he deems to have been entirely ineffective, and the Copenhagen talks should emphasize action by the United States and China.

I can’t argue with that, except to say that the world would be much happier — much more willing to join us in climate action — if we passed something like Waxman-Markey than if we passed the imaginary simple carbon tax.

No, Waxman-Markey won’t get us to 350-450 ppm, but it takes us off of the business as usual path, which is the most important thing, and it accelerates the transition to a clean energy economy, which is the second most important thing, and it establishes a framework that can be tightened as reality and science render inevitable. That is, after all, the same way we saved the ozone layer. The original Montréal protocol provisions would not have done so. But they got tightened overtime.

Hansen is right that it can take a few years (not decades) to establish a cap-and-trade system. That’s why we need to start now.