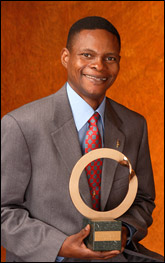

Corneille Ewango.

Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize.

In the vast Democratic Republic of the Congo, dense equatorial rainforests line the sprawling basin of the Congo River. Corneille E.N. Ewango, a Congolese botanist, has a particular appreciation for these lush stands, which represent about half of the continent’s tropical forests. To him, they are a scientific puzzle, a refuge for plants, wildlife, and people — and the place he considers home.

As the director of the botany program for the 3 million-acre Okapi Faunal Reserve, Ewango risked his life to protect these forests and their people. During his country’s civil war, which lasted from 1996 to 2002, Ewango saw the reserve threatened by mining, poaching, and widespread violence, but he refused to leave the area. He hid the reserve’s herbarium and other data, and even hid himself in the forest for three months.

After the war ended, Ewango received a scholarship to study tropical botany at the University of Missouri at St. Louis. When he finishes his master’s degree later this year, he plans to return to his work in the Congolese forests.

Corneille Ewango, 41, was awarded one of six 2005 Goldman Environmental Prizes at a ceremony in San Francisco on April 18. He spoke to Grist from San Francisco.

What first drew you to the natural world?

Congo, my country, has the largest forest in Africa, maybe the second-largest in the world. I was born in a forest area, and when I was growing up I assisted my uncle, who was a poacher. That was good, because it grew my passion for protecting the forest and plants. When I went to university, I decided that I would like to do something related to plant ecology, because I felt that plants were so beautiful. When I am studying plants, I feel like I am talking with some kind of supernatural life, like I am talking with someone who does not speak.

Would you tell me about the Okapi Faunal Reserve — what are its land, people, and wildlife like?

It’s in the northeastern Congo, and it protects the okapi, a forest giraffe found only in the north Congo. Its plants and animals are very diverse — so far we have identified about 700 species of plants, 400 species of trees and shrubs, and 300 species of lianas [forest vines]. There are 13 species of primates, and many different species of other large mammals, including antelopes. Before the war, it was estimated that there were 4,000 okapis in the forest and 4,500 forest elephants — we have a census going on right now to find out how many remain.

Ewango helped protect the endangered okapi, or forest giraffe.

Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize.

The reserve is also the homeland of Pygmies [Mbuti]. They are the first people who inhabited the forest, and their lives are closely related to it — they get everything important to their lives from the forest. I grew up in the western part of the country, and when I came to the reserve, in the east, I did not speak the dialect. I learned the language of the area, and now I can interact with the people. I feel like I am home.

After civil war broke out, you stayed at the okapi reserve while most of the rest of the senior staff fled. Why did you decide to stay?

When the war blew up, my colleagues were leaving the area, but I said, my history is here. I felt like leaving would mean leaving everything, leaving my life and my work — the work I was doing was related to my life. So I said, I think I will stay and take care of the field team, and see what is going to happen with the herbarium. If I had gone somewhere, I wouldn’t have gone to my homeland — my homeland is here. I prefer to die here, prefer that people know what I died for.

I understand you directly confronted military commanders in an effort to stop poaching of primates and elephants. What gave you the courage to take such a risk?

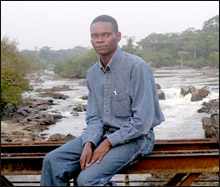

During the civil war, Ewango once hid out at the foot of this bridge.

Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize.

I kindly explained that they were destroying everything, and told them that having a protected area was going to increase their reputation outside [the country]. Sometimes we became friends, but sometimes they continued their activities. What I could not understand was that they killed an elephant in the village, very close to the zoo. I was very angry — I said you are joking, what kind of liberation or democracy are you fighting for if you are without law, if you are destroying everything? I said, it’s like you are killing your son and eating him, like you are not normal. They saw that I was strongly committed, and that I was serious.

What does the reserve look like today?

During that time [of the civil war], people have been doing whatever they want — there were mining camps everywhere, and problems controlling the reserve. It was like there were no laws. Now, it’s a bit more OK, because our team in the field has started working again. We are also developing a more ecological system of agriculture with the local people and communities.

How can people in industrialized countries help in the protection of places like the okapi reserve?

We have many problems as a country emerging from 10 years of war — the realization of our infrastructure, our socioeconomics. We depend so much on international NGOs giving more support to people working in the field, people working specifically for conservation. Pressure from northern countries can also stop other governments from supporting the militias, those that are occupying some of our most pristine areas.

What do you plan to do with the award money?

Though my country has the largest forest in Africa, it is one of the least known — we don’t have so much research in botany in the Congo, except what we are doing. I hope to build a new herbarium for protected-area flora — I’m thinking that this prize is an opportunity to finish that herbarium. For a long time, we have been working in the shadows, but now we see it coming into the light.