Paul Sabin is executive director of the Environmental Leadership Program and a lecturer in American history at Yale University. He is presently completing a book on California oil politics for the University of California Press.

Monday, 12 Aug 2002

NEW HAVEN, Conn.

I am off to Seattle today for a five-day retreat, and I’m tingling with anticipation. I’ll be joining three classes of fellows in the Environmental Leadership Program. Each year, we select about 25 extraordinary individuals from across the environmental movement. Coming from nonprofits, higher education, business, and government, these ELP fellows are “emerging leaders”– people with roughly three to 10 years of environmental experience who have begun to establish themselves in their field.

ELP fellows, staff, and board members at the August 2001 retreat.

Tomorrow, for the first time, all three of our classes of fellows will gather at the Sleeping Lady Conference Center in Leavenworth, Wash. I’m looking forward to this extended chance to build relationships across the environmental field — from environmental justice activism to conservation biology to corporate social responsibility. I’m always curious to see what will come out of the mix. We’ve seen two ELP fellows begin work on a documentary film about the health effects of hazardous waste on a tribal reservation in California.

I also am interested to see the results of the community-wide conversation about diversity that we have been undertaking for the past year. Since we met last August, we’ve been meeting, talking, and thinking about the social dimensions of environmentalism, exploring how differences in race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexual orientation, and faith influence our work as environmental activists and professionals. And since environmental politics also should be fun, we’ll host a festive “no-talent” show, hike in the nearby mountains, and swing our partners at a contra dance. I’ve been working towards this moment in ELP’s development since I first started envisioning the organization six years ago. I can’t quite believe we’ve reached this point — or that we’re ready to pull it off!

When I first dipped my toes in these waters, I was a graduate student in environmental history at Berkeley, just beginning a dissertation about California oil politics. At the time, I struggled to link my personal commitment to public outreach and social change with my training in American history. I knew that my study of how politics and public policy had shaped the California oil economy had direct implications for current energy policy. In the past few years, the California electricity crisis, the Enron debacle, the National Energy Plan, and climate change negotiations have underscored just how intertwined are energy and politics in the United States. Understanding the history of these politics, and how they helped get us where we are today, will be crucial to dealing with our current predicament.

ELP fellows discussing Activity Fund projects at August 2001 retreat.

Despite these clear connections, I didn’t feel trained, as most young academics don’t, to develop a public voice on pressing environmental issues or to link scholarship to policy. To the contrary, our relatively cautious academic culture and the tenure system force fledgling professors into a period of relative conformity, public silence, and isolation. By the time we come up for air post-tenure, many of us have lost social and professional connections to people outside the university and have been socialized to view pragmatic or political activities with great skepticism. I certainly felt this happening to me. Nor is it just academics who feel isolated. My peers at nonprofits and in government complained about burnout, lack of mentoring and connections to people outside their area of expertise, and an absence of opportunities for serious reflection, personal development, and leadership training.

While I struggled personally with these issues in the mid-1990s, on a broader scale progressives and environmentalists had grown increasingly aware of the role that public thinkers play in advancing economic, social and environmental policies. An influential 1997 report by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Moving a Public Policy Agenda: the Strategic Philanthropy of Conservative Foundations, documented how conservative donors had mobilized a powerful network of right-wing thinkers to influence national policy debates. One of the distinctive attributes of this strategic philanthropy was the long-term investment made in relatively young activists and thinkers. What were progressives doing to harness this kind of energy for their own causes? Progressive politics seemed too issue-based, short-term, and tentative.

With seed funding from the Nathan Cummings Foundation, I worked with 10 colleagues to design a new fellowship program for emerging environmental leaders. We sought to invest in the future of the environmental movement by training a new generation of leaders to shape the policy debate. We wanted to foster a community of risk-takers in different fields, people who would cross-fertilize the broader movement and support each other in their efforts to innovate. In the process, we sought to work with our fellows to develop new models for environmental leadership, ones that would emphasize diversity, collaboration across sectors, personal sustainability, and effective communication. We also sought to move beyond an elite, Washington, D.C., focus to develop leaders throughout the nation — people who could speak from a base of expertise, rather than as disconnected talking heads.

The colleagues with whom I launched the Environmental Leadership Program, who now serve mostly on the Board of Trustees or staff, were all in their late twenties or early thirties. We designed ELP around needs that we felt ourselves, and over the past three years, the staff and board have stayed closely involved. The retreat this week, when ELP will “graduate” its first class of fellows, is also a “coming of age” for the entire organization. And so I fly to Seattle to celebrate the first three years of our work, and to get ready to take the next steps.

Tuesday, 13 Aug 2002

SEATTLE, Wash.

I’ll spend today in Seattle, mainly working on fundraising and public outreach. As the director of a national organization, I have to maintain relationships with supporters and colleagues around the country. But with a delightful two-and-a-half-year-old son at home, I also try to avoid being on the road all the time. So I pack these travel days as tightly as possible; today I’ll woo potential funders at 9 a.m. and 1 p.m., and try to squeeze in lunch with an old friend in between.

Later in the day, I’ll search Seattle craft stores for ceremonial objects that we can present to the graduating class of fellows on Saturday. What might symbolize our journey over the past three years, and also capture our hopes for the future? I am thinking about those brightly colored, miniature Guatemalan ceramic buses, with the people inside and bananas and bags on the roof. Alternately, perhaps some small metal animal figures. Gift shopping is not my forte, but I’ll have to come up with something.

At 4:30, I’ll meet with ELP Advisory Committee member Wes Jackson, president of the Land Institute. I’ll bring Wes up to date on ELP, and then introduce him to a dozen ELP fellows who want to discuss sustainable agriculture. I expect that Wes will make the case to them that sustainability must start with agriculture. We should learn to mimic nature with skill, rather than dominate the natural world through monoculture industrial crop production. This meeting with Wes is the kind of informal intergenerational dialogue that ELP encourages, and I know that both Wes and the fellows are looking forward to it.

An ELP reception in San Francisco this spring.

Our big event today is a public reception from 6 to 8 p.m. at the Chinese Room at Smith Tower. (Come join us if you’re in Seattle — we’ll be on the 35th floor!) We expect more than 100 people to come meet many of the ELP fellows and learn about the organization. Most of our guests will be others working in the environmental field, though we also hope to impress a few individuals who might give money to support our work. Denis Hayes, president of the Bullitt Foundation and longtime environmental activist, will be our special guest speaker, offering his thoughts on environmental leadership. We also will show several video profiles that ELP fellow Robert Rosenheck has made of his colleagues, part of an ELP documentary film project and publicity effort. Most important, we expect 30 ELP fellows to come. Since this week’s retreat agenda is jammed with activities, I’m glad that people will have this extra time just to chat with each other and with our guests.

Fundraising and networking is a big part of being an executive director. I enjoy it, in moderation. Getting to make the pitch for ELP keeps me connected to the passion and ideas that drew me to this work. I get to talk about the changing face of the environmental movement, the need to develop our future leaders, and the inspiring work of the ELP fellows. I particularly relish the debate when a foundation program officer asks hard questions that force me to question my usual assumptions.

Yet raising money for an environmental leadership organization is also difficult. Environmentalists talk a lot about the future, but we have not invested very much in it. Or, rather, we have invested huge sums of money to buy land and litigate development projects, but far less in developing a working society and economy that will support environmental protection. This is one key lesson from the study of conservative philanthropy: the importance of investing in people, ideas, and networks. By contrast, the environmental movement and environmental grantmakers tend to focus on more narrow, short-term issues. We also tend to churn through our young people, rather than investing in their development for the future. Our strategy often wins battles, but it does not build a long-term movement, and it has not shifted the terms of the political debate far enough. Environmentalists remain stuck reacting to the big ideas and political maneuvering of the opposition.

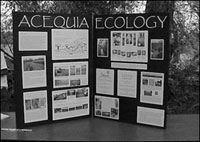

An educational display from an Activity Fund project.

The Environmental Leadership Program has its own short-term accomplishments, and we wouldn’t survive in this tough funding world without them. With support from the ELP Activity Fund, for instance, ELP fellows have already launched new organizations, organized conferences, written books, tested lead levels in children, and published op-ed articles in newspapers and magazines around the country.

Yet the long-term value of the ELP network is even more important than these impressive accomplishments. What we really hope to achieve is harder to measure: community dialogue that will mobilize individuals to act over the course of their careers, and that will spill over into the broader environmental field. Over the past year, we have been talking a lot, formally and informally, about diversity in the environmental community. On Thursday and Friday, we’ll hold diversity workshops to help prepare ELP fellows to take the lead on diversity issues within their communities and organizations.

Following the retreat, we hope to develop a book of essays by ELP fellows on the social dynamics of environmentalism, and to hold outreach events to work with emerging environmental leaders beyond the ELP fellowship. Our goal: to use our hive of activity to help spur environmentalists across the country to think more deeply about how race, class, gender, and other social differences shape our collective work. This is the right thing to do, and also a political necessity, since the future political success of the environmental movement depends on broader constituencies. But in order to make progress in this area, we need to take some time for reflection and dialogue, and embrace a longer-term view of environmental politics and leadership.

Wednesday, 14 Aug 2002

SEATTLE, Wash.

What a fabulous reception! The event was held on the 35th floor of Smith Tower, which was built in 1914 and, on yesterday’s clear evening, boasted a spectacular 360-degree view of Seattle and the mountains. Over 100 people showed up and the place was buzzing. Denis Hayes spoke about the need to invest in leadership development and to reach out more effectively to middle America, as well as the importance of bold risk-taking. ELP fellow Jonna Higgins-Freese, from the Prairiewoods Franciscan Spirituality Center, described the transformative impact that the ELP fellowship program has had on her life over the past few years, crediting it with keeping her inspired and active in her environmental work.

Jonna told two stories about how the ELP experiences had created opportunities for collaboration with people quite different from her. By learning to work with a private sector fellow of whom she had been dismissive at the first meeting, she gained access to a valuable source of advice on business and marketing, which she used to strengthen a local wine- and grape-purchasing program for Iowa churches. And by learning more about environmental justice issues, she was inspired to co-author, with Jeff Tomhave, an article for a spirituality magazine on the environmental challenges tribal communities face today and the diversity of Native American spiritual beliefs.

Though she did not speak about it, Jonna has also broadened the horizons of her ELP colleagues by introducing them to faith-based environmental action. Jonna’s experience within ELP illustrates the creative ferment that comes from the incredible diversity of the ELP fellowship community. Many leadership programs in environmentalism work with narrow subsets of the field — a training program for state-based wilderness advocates, for example, or for field organizers, or for academic scientists. By contrast, ELP strives for diversity in the recruitment and selection of ELP fellows. We seek to weave together the different strands of the environmental movement into one complex fabric.

I’m pretty sure that the ELP fellowship community is unique in the environmental field. I can’t imagine where else you’d find environmental justice activists, corporate environmental managers, conservation biologists, historians, tribal managers, labor organizers, and faith-based coordinators working together over a period of years. Our fellows are split fairly evenly among four major sectors of society: nonprofits, higher education, government, and the private sector. They are also geographically diverse, drawing from more than half the states in the first three years. The community is balanced by gender, and almost half the fellows are people of color.

This diversity reflects the fundamental ways the environmental movement is changing. Environmental leadership is found increasingly beyond the Beltway and across the country. In addition, environmentalism has penetrated every sector of society, and people are striving to transform our major institutions (including corporations, government agencies, and universities), often from within.

What it means to do environmental work also has changed. For instance, Alan Hipolito, an ELP fellow, has spent much of the past few years developing a credit union for a Latino neighborhood in Portland, Ore. The idea is that a vibrant community with opportunities for local capital accumulation and economic development can make “smart growth” also be “just growth,” meeting the needs of low-income communities of color. This broadening and redefining of environmentalism is increasingly important as we begin to try integrating ecological sustainability with economic development and social equity.

The heterogeneity of the ELP fellowship community is a key asset in helping ELP fellows conceive of their work in broad terms, develop new networks, and deepen their insights. In our efforts to stimulate collaboration across sectors and profound social divisions, we don’t expect the fellows to change who they are so much as to learn to communicate and build coalitions across divisions, and to understand where others are coming from.

The Sleeping Lady.

Today, I am heading off with four staff members for the Sleeping Lady retreat center at 7 a.m. The rest of the fellows and staff will follow later, but some of us need to arrive early to check out meeting spaces and make last-minute arrangements.

Before I started directing ELP, I didn’t think much about whether a meeting space or time would be particularly conducive to a good discussion. I also paid relatively little attention to group process — team-building and all that stuff. But I’ve grown more humble about my own learning style. I’ve come to recognize that we need to craft agendas that include ritual and ceremony, plans that will work for abstract, conceptual thinkers like me, as well as impassioned, visual “doers.”

I wonder whether a little more attention to the culture of how we do our work might help the environmental community enhance its appeal to a greater number of people. The gap that we bridge among ELP fellows seems like a microcosm of the larger gap between lawyers, public health professionals, scientists, and grassroots activists.

This afternoon, we’ll begin by introducing the different fellowship classes to each other and getting people comfortable with being together at the retreat. We’ll do some team-building activities. We’ll have a healthy block of free time, since some of the most important conversations are the impromptu ones. And we’ll end the evening with a contra dance. I haven’t contra danced for more than a decade, but I used to love it. I can’t wait.

Thursday, 15 Aug 2002

LEAVENWORTH, Wash.

The Sleeping Lady retreat center is located in a spectacular canyon with a beautiful creek running through it, so we couldn’t help but get off to a great start yesterday. We did a lot of good talking throughout the afternoon. We also plunged into the aptly named Icicle Creek and, later, strutted our stuff on the dance floor. As our host Harriet Bullitt told us last night, why should you have to wear a hair shirt to be an environmentalist?

Walking back from Icicle Creek.

Emilio Williams.

People are energized to be here and it’s a thrill to see the community come together. I had wondered whether it would be too unmanageable to have three classes of fellows meeting at once. But so far, it seems to be great. Whenever there is a lull in the structured program, the conversations surge ahead.

I’m pleased to feel this positive energy in the group, since we’ll need it to carry us through a busy and challenging day. We’ll start off with an Activity Fund fair. Each member of the second and third class of fellows will present a possible leadership project and then have a chance to talk about it with others mingling through the fair. This is a great opportunity to learn about the issues that people face in their work, and to hear about their ideas for innovation and personal learning. Then, this afternoon and tomorrow morning, we’ll talk about diversity in the environmental field, and particularly about race, class, gender, and questions of privilege. Since these aren’t easy topics, we’ll work in separate fellowship classes to create a relatively safe space for conversation. We’ll also divide into race and ethnicity “caucuses” and professional sector groupings to allow more focused discussion.

Socializing before tackling social issues.

Emilia Williams.

It may seem strange for an environmental leadership program to spend so much time talking about broad social issues. Yet one of the main things we’ve learned over the past three years is that it isn’t enough to “do” diversity by bringing people together across lines of race, class, professional sector, and so forth. Diversity is too big and too messy a part of American life for action alone to succeed. Instead, we’ve found it necessary to push people to think about the personal and societal baggage they bring with them to the group, and to their work at large — though it’s sometimes tricky to figure out how far the pushing should go.

Why do we care so much about diversity? The answer is that we think the environmental movement needs to expand its constituency to be effective in the coming years. As I noted yesterday, we hope to help broaden the definition of what it means to be an environmentalist and to connect the environmental movement to groups that historically have been underrepresented in environmental politics: people of color and various ethnicities, and people outside the upper-middle class. Simply put, we think that too often, being green has meant being white and/or well-off.

At past retreats, some fellows have expressed frustration about these diversity conversations. Some have asked whether probing these social divisions within the environmental community weakens us internally, rather than help focus our collective efforts on behalf of the environment. Others have felt that these conversations haven’t gone far enough. Talking about racism and privilege has led some ELP fellows to reveal deep reserves of anger and hurt based on personal experience. Sometimes these feelings have been hard to say and hard to hear. We’re still figuring out how to make sure that we frame these discussions in a safe way. Different people are comfortable with different levels of intimacy and candor, and sometimes people need to remember to speak or listen with an open heart.

The challenges we face raise serious questions about how the environmental movement is going to deal with issues of equity and privilege. One conclusion that I draw from our experience is that the environmental community needs to spend a whole lot more time talking internally about diversity, in addition to taking practical action through hiring processes and leadership programs. Until we can talk more comfortably about privilege and equity, and about the limits that we each face in wrestling with these hard topics, we’ll lack the skill to deal with inevitable misunderstanding and conflict.

On a personal level, I continue to deepen my understanding of my own limitations. I’ve come to see more fully how tightly a mask of identity covers my face — the stamp of white, male, executive director, Yale, well-off, New England, secular, Jewish, academic. That’s a lot of baggage in a conversation about diversity. But when you get right down to it, I think it may not be much more or less than any other person carries. I’m working on seeing how different people have different understandings of what’s going on in the room; on remembering that many people see my mask and don’t necessarily hear me until long afterwards; and on embracing the responsibilities and challenges that fall to me as a result of my societal position. I am also experimenting with speaking candidly about these issues, in one-on-one conversations and in front of the entire ELP group. Reflection and self-awareness is a big part of what we are teaching in the ELP fellowship program, and, thankfully, I’m learning, too.

Friday, 16 Aug 2002

LEAVENWORTH, Wash.

I can’t believe I’m writing this column right now. Who persuaded me to do this? I’ve got a foundation program officer to say goodbye to and a session to plan for this afternoon. I also want to snoop around the sector caucuses to see what they’re saying. I called my Grist editor to request a brief reprieve, but still, I’ll have to bang this out quickly.

Discussing diversity at the spring 2002 retreat.

Yesterday’s diversity discussions went as well as one might have hoped. No big blow-ups, some frustration, some small steps forward. We have to manage our expectations here in ELP and, by extension, in the environmental community. People often come to these discussions hoping that something cathartic will happen, that we will arrive at the other side cleansed, united, and with a clear plan of action. Needless to say, that’s a lot to ask from a one-day discussion.

I measure success by the conversations that come afterwards. It’s clear that the group discussions opened up the topic. People were up late socializing and rehashing the day’s events. This processing, revisiting, and note-comparing is crucial to our learning to talk about these challenging issues. This morning, the different groups represented here — education, nonprofits, business, and government — were having lively discussions, including a lot of personal story-sharing about people’s work. As we talk about diversity, we’re also learning about each other’s workplaces, strategies for change, and personal experiences and world views.

As I walk among the different small-group discussions taking place outside in various shady spots, I am reminded of my first attempt to start a leadership program. The summer after my first year in college, I returned to the Boys and Girls Camps organization where I had worked for two summers as a counselor for kids from Boston and Cambridge. The camp director asked me to develop a “Leaders-in-Training” program for young people who were too old for camp.

What a summer! The tents flooded the first night, drenching everything. I remember taking my kids on an overnight hike to see a lunar eclipse — only to find that all they wanted to do on the mountain was play Truth or Dare. I laugh at the memories, and at myself. We had a lot of good times, but by the end of the summer, I was so burnt out that I dropped out of activism and channeled my energies into academics. Today, with our continued diversity work, I feel proud to have come full circle in a sense, returning to leadership development with greater maturity and skill, again in the context of integrating environmental concerns with questions of race, class, and privilege.

This afternoon, after we conclude the structured diversity training, we will move into concurrent sessions. I’ll moderate a three-hour double session on the history and future of environmental politics in the U.S. University of Wisconsin historian William Cronon, along with three academic ELP fellows, will talk about land conservation, public health, urban planning, and the relevance of history to our current politics. A communications trainer will lead sessions on using reports to influence public debate about the environment and to develop communications plans. Three fellows will present their Activity Fund project, which explores the role that intermediary experts play in the environmental justice movement. And tonight we’ll have a campfire discussion and screen the ELP video documentary. Still two more days left, but I’m relaxed and feeling good about how the meeting is going.

I just might try to squeeze in a dip in Icicle Creek before the next session.