To avoid the most disastrous sea-level rise, storms, heat waves, and drought, the best available science says that greenhouse gas emissions must be cut in half in the next decade or so and brought to net-zero by the middle of the century.

But even if global leaders acted to cut emissions at that breakneck pace — which none currently has — many of those catastrophic outcomes could still occur. The science of human-caused climate change is unequivocal, but the science of projecting how bad things will get, how quickly, is soaked in uncertainty.

It’s possible that the dangers will reach a critical juncture where the world may want to consider another tool with the potential to save millions of lives: solar geoengineering, also described by scientists with the more careful and lengthy phrase “climate intervention strategies that reflect sunlight to cool the earth.”

Deliberately changing the atmosphere to try to cool down the planet is deeply uncomfortable to think about, and many would prefer that no one did. But for the past two years, a committee of 16 people with various expertise in the physical sciences, economics, policy, law, and ethics have been sitting with that discomfort as they met regularly to develop an American research agenda for this nascent and highly controversial field of science.

The result of those many hours of discussion and debate is a more than 300-page guide for the U.S. government to spend at least $100 million on a new solar geoengineering research program. It was released on Thursday by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, a nonprofit that acts as an independent advisor to the federal government.

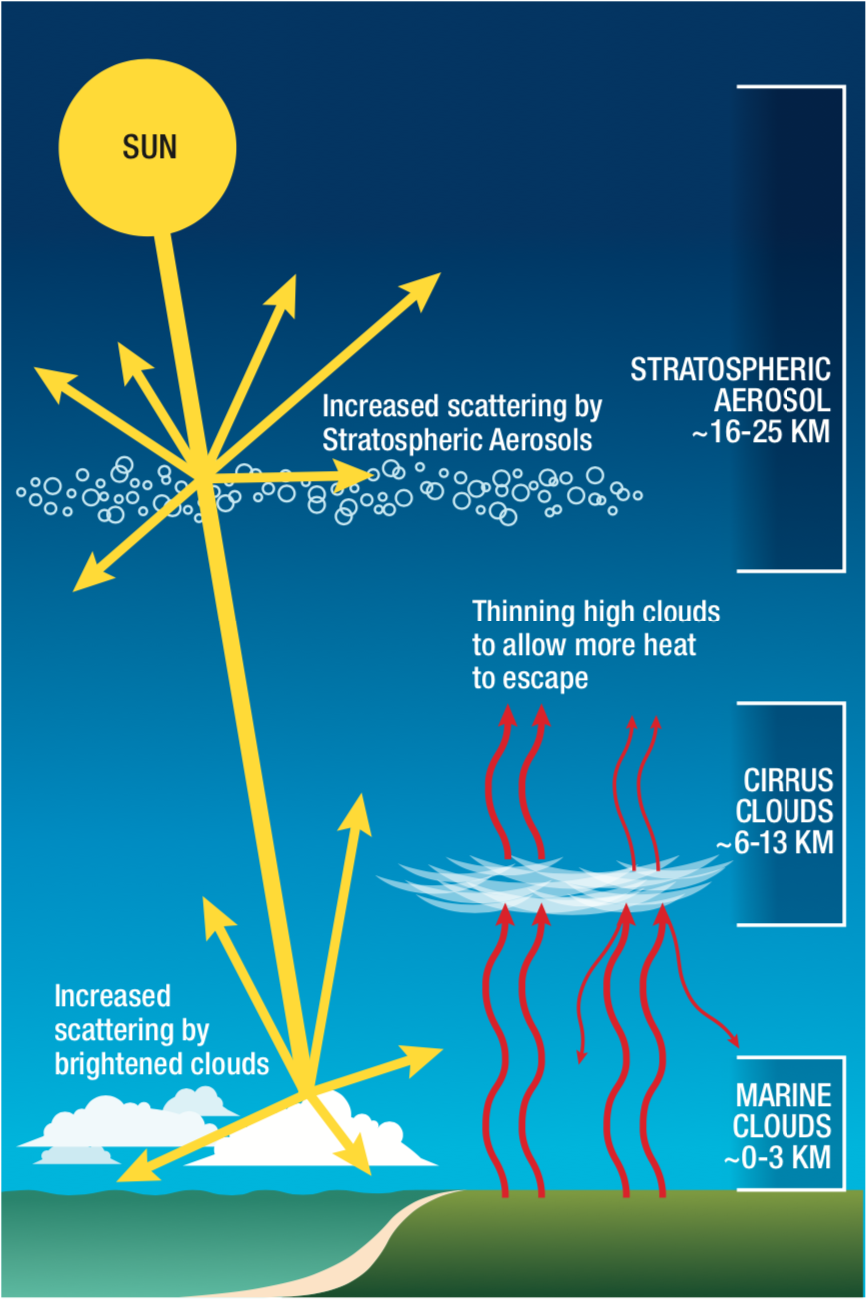

The strategies under consideration include shooting particles into the atmosphere to increase the amount of sunlight reflected back into space and seeding cirrus clouds with particles that thin them to allow more heat from the earth to escape. These interventions could reduce global average temperatures quickly but temporarily, potentially staving off dangerous extreme weather and other effects of climate change. However, they also may inflict harms of their own and would be akin to a Band-Aid, not having any effect on the underlying cause of temperature rise — the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere.

No one involved with the report recommends that the U.S. or anyone else prepare to do solar geoengineering now, or ever. The report argues that there has not been nearly enough research on the subject to make informed decisions one way or the other.

The committee, which was funded by several government agencies and philanthropic foundations, had two assignments: First, to identify what kind of research is needed to improve understanding of the potential benefits and risks of these interventions. Second, to make recommendations for systems of oversight that would ensure solar geoengineering research is appropriate, safe, and transparent; invite public engagement; and address any social, ethical, and legal concerns.

Many environmental advocates have suggested that even researching solar geoengineering normalizes the idea, making it far more likely to come to fruition. Bill McKibben, writing recently in The New Yorker about a geoengineering experiment proposed by Harvard scientists, warned that such research is a distraction from the more urgent work of cutting emissions. “It’s an ominous moment in the planet’s history — and one we should back away from for now,” he wrote. (Editor’s note: McKibben is a member of Grist’s board of directors.)

But part of the thinking behind the new report is that this research is already happening, said Marion Hourdequin, an environmental philosophy professor at Colorado College and one of the committee members. Except it’s happening in an ad hoc, fragmented way, across many disciplines, and with varying degrees of public engagement.

It’s also largely funded by philanthropy, which is not accountable to the public the way a government agency is. Between 2008 and 2018, U.S. solar geoengineering research received approximately $18 million from private sources and $7 million in federal dollars.

“A research program would help draw together different strands of research and hopefully put researchers from different disciplines in conversation with one another,” said Hourdequin, “That can help ensure that we’re asking the right questions, and that the overall approach is informed by consideration of issues of justice, equity, ethics.”

Another committee member, Lynn Russell, an atmospheric scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said that a national research program could address a number of important questions, not just about geoengineering but also about climate change. Right now, clouds are one of the least understood factors in climate change research. “We have a lot of conflicting results about how cloud cover will change as the planet warms,” she said.

Two possible interventions that could cool the planet involve altering clouds. In addition to thinning cirrus clouds, scientists have also proposed spraying a fine mist of seawater into clouds over the ocean to brighten them, allowing them to scatter incoming sunlight. Russell said research into cloud brightening could inform scientists’ understanding of “how much global warming will increase temperatures, and how soon, and where.”

The report lays out a five-year research plan — which is not intended as a path to deployment. It recommends spending $100 million to $200 million over that period, to be overseen by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, which already coordinates research across federal agencies. In a separate report released earlier this month, the National Academies already advised the Global Change Research Program to shift its focus away from studying the effects of climate change to research that will help society prepare for the risks.

The geoengineering report recommends a menu of basic scientific research into the atmospheric processes that would govern the proposed interventions, the possible effects interventions would have on the climate and environment, and the technical requirements for each strategy. Experiments that involve the release of particles outdoors should be subject to additional oversight, engagement, and permitting, and pursued only if there is no other way to make the same observations. The social and ethical dimensions of this research should also be studied, and a continuation of the committee’s work — further deliberation about what research it needed and how it should be governed — is recommended.

“There needs to be a lot of feedback between the findings and what to do next,” said Russell. To enable that feedback, the committee recommends mechanisms of transparency like a code of conduct, a public registry of research, data and information sharing among researchers, and public engagement processes. Solar geoengineering is international in scope and effect, and so international collaboration should be a priority, with the research regularly reviewed by a diverse group of stakeholders, including from the nations and communities most vulnerable to climate change.

A key facet to this feedback process is the inclusion of exit ramps, described in the report as criteria and protocols to end a research program. Based on what is learned, scientists, advisory boards, and policymakers can either decide to continue with certain lines of study, and provide more funding, or perhaps decide that the risks are simply too high, and scale it back. Hourdequin said that’s a departure from how research and innovation traditionally occur, where it’s often not until a technology has been developed that society gets to decide how and whether to use it.

The recommendations in the report attempt to braid social perspectives throughout the research process, she said, “so that the questions that are most salient to policymakers, to various publics, to different countries around the world — those actually inform the kinds of questions that researchers are asking, and help frame the way in which research on solar geoengineering unfolds over time.”