This story was originally published by the Guardian and the Correspondent and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The oil giant Shell issued a stark warning of the catastrophic risks of climate change more than a quarter of century ago in a prescient 1991 film that has been rediscovered.

However, since then, the company has invested heavily in highly polluting oil reserves and helped lobby against climate action, leading to accusations that Shell knew the grave risks of global warming, but did not act accordingly.

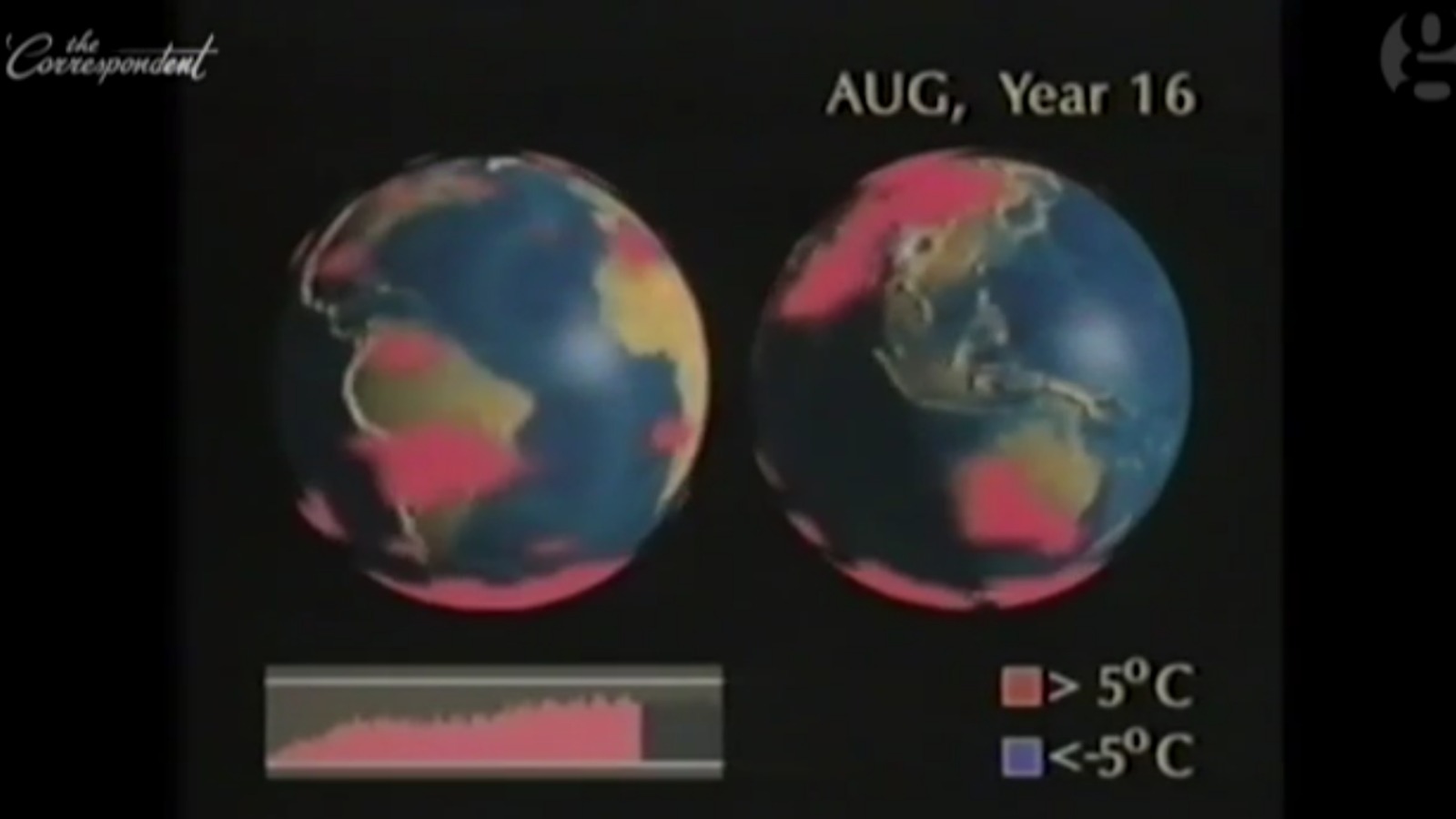

Shell’s 28-minute film, called Climate of Concern, was made for public viewing, particularly in schools and universities. It warned of extreme weather, floods, famines, and climate refugees as fossil fuel burning warmed the world. The serious warning was “endorsed by a uniquely broad consensus of scientists in their report to the United Nations at the end of 1990,” the film noted.

“If the weather machine were to be wound up to such new levels of energy, no country would remain unaffected,” it says. “Global warming is not yet certain, but many think that to wait for final proof would be irresponsible. Action now is seen as the only safe insurance.”

A separate 1986 report, marked “confidential” and also seen by the Guardian, notes the large uncertainties in climate science at the time but nonetheless states: “The changes may be the greatest in recorded history.”

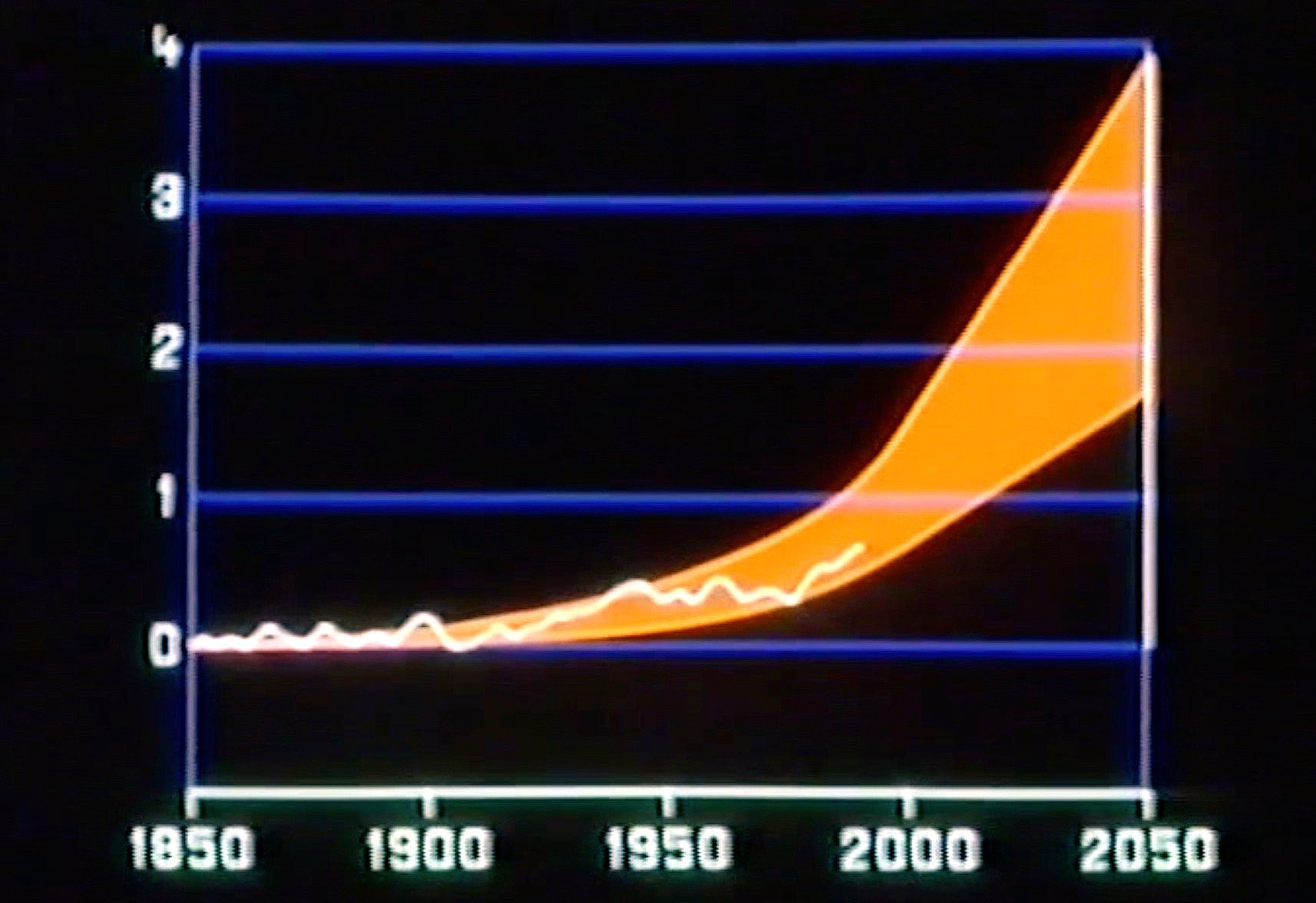

The predictions in the 1991 film for temperature and sea-level rises and their impacts were remarkably accurate, according to scientists, and Shell was one of the first major oil companies to accept the reality and dangers of climate change.

But, despite this early and clear-eyed view of the risks of global warming, Shell invested many billions of dollars in highly polluting tar-sands operations and on exploration in the Arctic. It also cited fracking as a “future opportunity” in 2016, despite its own 1998 data showing exploitation of unconventional oil and gas was incompatible with climate goals.

The projections for future global warming in Shell’s 1991 film stand up “pretty well” today, according to climate scientist Tom Wigley. Climate of Concern

The film was obtained by the Correspondent, a Dutch online journalism platform, and shared with the Guardian, and lauds commercial-scale solar and wind power that already existed in 1991. Shell has recently lobbied successfully to undermine European renewable energy targets and is estimated to have spent $22 million in 2015 lobbying against climate policies. The company’s investments in low-carbon energy have been minimal compared to its fossil fuel investments.

Shell has also been a member of industry lobby groups that have fought climate action, including the so-called Global Climate Coalition until 1998; the far-right American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) until 2015; and remains a member of the Business Roundtable and the American Petroleum Institute today.

Another oil giant, ExxonMobil, is under investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and state attorney generals for allegedly misleading investors about the risks climate change posed to its business. The company said it is confident it is compliant. In early 2016, a group of congressmen asked the Department of Justice to also “investigate whether Shell’s actions around climate change violated federal law.”

“They knew. Shell told the public the truth about climate change in 1991 and they clearly never got round to telling their own board of directors,” said Tom Burke at the green think tank E3G, who was a member of Shell’s external review committee from 2012–2014 and has also advised BP and the mining giant Rio Tinto. “Shell’s behavior now is risky for the climate but it is also risky for their shareholders. It is very difficult to explain why they are continuing to explore and develop high-cost reserves.”

Bill McKibben, a leading U.S. environmentalist, said: “The fact that Shell understood all this in 1991, and that a quarter-century later it was trying to open up the Arctic to oil-drilling, tells you all you’ll ever need to know about the corporate ethic of the fossil fuel industry. Shell made a big difference in the world — a difference for the worse.”

Tom Wigley, the climate scientist who was head of the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia when it helped Shell with the 1991 film, said: “It’s one of the best little films that I have seen on climate change ever. One could show this today and almost all would still be relevant.” He said Shell’s actions since 1991 had “absolutely not” been consistent with the film’s warning.

A Shell spokesperson said: “Our position on climate change is well known; recognizing the climate challenge and the role energy has in enabling a decent quality of life. Shell continues to call for effective policy to support lower carbon business and consumer choices and opportunities such as government lead carbon pricing/trading schemes.

“Today, Shell applies a $40 per tonne of CO2 internal project screening value to project decision-making and has developed leadership positions in natural gas and sugarcane ethanol; the lowest carbon hydrocarbon and biofuel respectively,” she said.

Patricia Espinosa, the U.N.’s climate change chief, said change by the big oil companies was vital to tackling global warming. “They are a big part of the global economy, so if we do not get them on board, we will not be able to achieve this transformation of the economy we need,” she said.

The investments the oil majors are making in clean energy are, Espinosa said, “very small, the activities in which they are engaging are still small and do not have the impact that we really need.”

Espinosa, who visited Shell’s headquarters in the Hague in December, said: “They are clear that this [climate change] agenda has to do with the future of their company and that business as usual, not doing anything, will lead to crisis and losses in their business.”