Deborah Tabart is executive director of the Australian Koala Foundation, an independent organization dedicated to the conservation of the koala and its habitat.

Monday, 11 Sep 2000

BRISBANE, Australia

When the Olympics begin this Friday, the world will be watching Australia. Beautiful images of koalas will be beamed across the globe, but there will be no mention that koalas in the wild face a series of threats, foremost habitat destruction.

Won’t you be my mascot?

The koala is one of the most well-loved and well-recognized Aussie animals, second only to the kangaroo. This year, the world will be meeting the Olympic mascots — Ollie (an echidna), Millie (a platypus), and Syd (a kookaburra) — examples of the beautiful and extraordinary fauna that are native to Australia. But I am really disappointed that the koala wasn’t chosen as an Olympic mascot.

The koala is a symbol of what we all love about Australia — the bush, our identity, national pride — and it could be the flagship for conservation. It is my personal view that our Olympic organizers did not choose the koala as a mascot because there is such a strong conservation lobby for the protection of its habitat. And at some point, someone would ask the question, “Is the koala safe?” And the answer would be, “No!”

Koala conservation isn’t as romantic or clear-cut as one might think. Most koala populations — we estimate 80 percent — live on privately owned land, most of which is not protected by legislation, and that means there is virtually nothing that can stop landholders from doing what they want with their property, even if it is detrimental to koalas.

Many of our significant koala habitats are under pressure from suburbia, from ordinary Australians who are wanting to live the Australian dream of their own bit of land with a house and a backyard.

Did you know that over 90 percent of the Australian population lives in coastal cities and towns, not in the bush? We are definitely not all like Crocodile Dundee (although many of us would like to think we are!). If you look at a map of where koalas live and where people live, they overlap because we both like the fertile coastal strip. Koalas compete directly with humans for land.

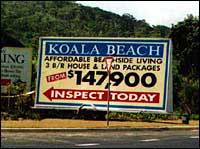

This sign reminds motorists to share the road with koalas.

My office is situated in Brisbane, very close to the center of one of the largest remaining urban koala populations in the country. In fact, my office is probably built on land where there were once koalas roaming free. The area surrounding Brisbane is now under immense pressure from development — new roads, new housing estates, new shopping centers.

The local koala hospital admits approximately 1,200 koalas each year, and only about 250 go back to the wild. The pressure on them is immense. The population of koalas in Brisbane, living in an area of about 25,000 acres, is estimated to be 5,000 to 7,000 animals. How long can they suffer this rate of loss?

I do not think that Brisbane’s local koala population will survive. There are too many urban pressures on it. I am not liked for saying this, but the figures speak for themselves. Many people involved in conservation say that if you tell the truth about how hopeless the future looks, it will depress those we need to inspire. But I think it is time to tell it like it is and hope that the citizens and politicians alike wake up.

Until there is a real commitment by government to address the issues that threaten koalas — habitat loss and fragmentation, cars, dogs, disease, bushfire — their population decline will continue. The Australian Koala Foundation is pushing for a National Koala Act to tackle these problems.

Developments are approved one by one, with no big picture in mind. We need to set aside key areas and then educate the people who live nearby and give them incentives to plant indigenous trees that can serve as koala habitat. We need to encourage people to drive carefully, especially at night when koalas are likely to cross the road, and to be responsible dog owners (dogs are a major killer of koalas). People need to become conservationists in their own backyards.

Often I’m amazed at how hard it is to convince people from overseas that koalas get run over on the roads or attacked by dogs. American zoo visitors see koalas as precious and honored, as they should be, and I suspect it is almost impossible for them to think of koalas facing perils like car accidents, but it happens every day.

Suburbia is sprawling across koala country.

Australians have the same problem. Most Aussies have never seen a wild koala, and they don’t think of their trees as being part of what sustains them. Most people love koalas and want to “save” them, but don’t associate expansion of towns and cities as part of the problem.

Tomorrow I’m going to meet with a developer on the northern coast of New South Wales near a little town called Pottsville. We’ve been collaborating with him for five years now, encouraging ordinary people to become koala conservationists by living in a residential estate that has koala protection as a major goal. In this area, residents are educated about koalas and their needs, trees that provide habitat are protected, traffic speeds are reduced, and no cats and dogs are allowed.

This developer and the AKF have formed an unusual alliance, one that is still new in this country, and we both hope that it will lead the way to a truly sustainable Australia where humans and wildlife live in harmony.

Tuesday, 12 Sep 2000

KOALA BEACH, Pottsville, New South Wales

We’re meeting this morning with developer Brian Ray and project manager Steve McRae to discuss stages three, four, and five of the Koala Beach development — the first koala-friendly housing estate (in the U.S. you’d call it a subdivision) to be built in consultation with the Australian Koala Foundation.

Can development be koala-friendly?

This is an unusual alliance, one that was hard won. During our original negotiations, many people in the community did not trust this alliance. Many felt that AKF had compromised its integrity by working with a developer, but I believe very strongly that unless we look for solutions like Koala Beach and work proactively with the people who own the land, we’ll never have a hope of saving the koala. Many of these landholders need direction in terms of environmental management and we need to be there with them — walking the hard yards with them,influencing them with our ethics and belief in conservation, and listening to the problems they face.

Koala Beach is a residential community within one of the most beautiful areas of coastal bushland in northern New South Wales and it has been designed to sit gently amongst the bush and animals that surround it. Koalas, sugar gliders, swamp wallabies, blossom bats, glossy black cockatoos, bandicoots, ring-tailed possums, green tree frogs, curlews, lorikeets, king parrots, and many other species live there.

In the past the land was grazed for cattle, farmed for market vegetables, and at one time supported a piggery.

Like much of the surrounding farming land, it is now being urbanized as the human population presses south from the Gold Coast, which itself is south of Brisbane. (The continual growth along our eastern seaboard is comparable to the growth along the west coast of the U.S.)

Koalas are running short on places to curl up.

We’ve been doing fieldwork in this area for about five years and over that time we’ve seen significant changes. Once there was only a little bakery (with excellent vanilla slices — an Australian pastry to die for), a pub, a service (gas) station, and a fruit and veggie shop. Now there are new roads, new shopping centers, and more and more houses. You can feel the pressure on Koala Beach already. It will, one day, be surrounded by housing estates where there are no measures to protect wildlife or the environment. I often wonder what will happen, because even if we put everything in place to protect the koalas that live there, there is no guarantee that they will survive long term because of the impacts of all those people and their dogs, cats, and cars. Sometimes the situation can feel futile.

With 80 percent of koala habitat on privately owned land, we need to give direction to planners, landowners, and people who come to live here. We need to avoid mindless urban sprawl and create places where people want to live, places that nourish people’s souls and social needs as well as the koalas and other wildlife.

I don’t think we can dictate to people what they can and cannot do. All we can do is tell them how they can help the koalas and other animals survive and hope they will listen. Will they make the necessary changes to their lifestyles? Will they tie up their dogs at night? Will they not own a dog? (I myself own three and know the joy they bring me.) Will they reduce the speed of their cars when driving through koala habitats? I don’t know the answer to these questions, but I suspect that people would change if they knew the gravity of the situation.

A koala in a tree, happy as can be.

Brian Ray has walked a long way with us. Sometimes his developer friends think he’s a bit strange for working with us, but to his credit he has stuck with the constraints we’ve placed on the development, like prohibiting cats and dogs, keeping special koala home trees, etc. Most notably, he has dedicated some 500 of 750 acres of bushland to be preserved forever to support the animals and plants that live there. This is a huge commitment to conservation. How many of us would give up nearly 500 acres to protect wildlife?

Today we are discussing whether the new stages of the development will also have a dog ban. Sales of the first stages were slow and many say it is because people do not want to give up their beloved pets to live with wildlife.

It’s such a complex issue. We want the dog ban because dogs kill koalas and even having one dog on site could wreak havoc. Lifting the dog ban would give a clear message to people that we have had to compromise. What would that compromise mean to the koalas on the site? Could we keep the dogs under control? Would the people on the site still understand that they have to be responsible? Many questions today.

The lesson I have learned from working with Brian is that some areas of koala habitat should never be developed. Koala Beach is core koala habitat, and any dog will destroy a colony living there. But I am sure that less sensitive habitat could be managed differently.

Perhaps if we had a National Koala Act in place, things could have been different. We might have been able to buy this land from Brian. The government might have determined that it was too precious to develop.

I will have to make the hard decision about whether to lift the dog ban. The buck will stop with me. I will have to think of what is best for the koalas and for humans, since we must live somewhere .

It’s going to be an interesting day!

Wednesday, 13 Sep 2000

ON THE ROAD, New South Wales

Overnight I heard the curlews calling on Koala Beach — bush-stone curlews are an endangered species and have been nesting at Koala Beach for the last two seasons. Last year they had two chicks, but unfortunately one was killed by a car and the other is thought to have been taken by a fox — there are feral foxes on the estate. Foxes are not native to Australia; they were brought here 200 years ago by the English for fox hunting and since that time they have caused havoc with all small marsupials and birds. The management committee on Koala Beach is now trying to reduce the number of foxes on the site.

Curlews at Koala Beach.

Yesterday was an interesting day — we had pretty intense but mind-expanding discussions. We are at a stalemate about whether to impose the dog ban on the next stages of development at Koala Beach.

Here are the issues I have to think about:

- If we lift the ban, what will be the long-term consequences for the koalas? Can we lift the ban and still protect them?

- If we do not lift the ban, what will happen? The sales of the development could stop, the development could go broke, and then at some stage in the future people would not take the necessary steps to protect the koalas.

Even if we don’t lift the dog ban at Koala Beach, this is an issue we must eventually face. Many of us have cats and dogs and gain great pleasure and solace from close interaction with them — we don’t want to live without them.

Furry friend or marsupial marauder?

I am a responsible dog owner. My three golden retrievers go to bed each evening, out of harm’s way. However, as gentle as they look, they would love to kill a koala if given the chance and indeed they have killed a possum on my property.

Could I live at Koala Beach without my dogs? What would encourage me to live there without them?

Current residents at Koala Beach love living there because the only sound they hear is “the sound of the sea.” No dogs barking. Are there enough people in Australia to buy this development who do not want to have a dog?

These are the issues in a nutshell. Those of you reading this may well want to write to me with advice. I will need it.

Often human dignity and respect are missing from the conservation debate — people say “they should do this,” “they shouldn’t be allowed to do that,” “they must do such and such.” I always come back to thinking about what my reaction would be if I had restrictions imposed on me and my home and my land. I have three dogs — in fact four out of five of our AKF staff who met with Brian Ray yesterday own dogs. Would any of us be willing to have them put down or give them away in order to live at Koala Beach? It’s such a hard decision to make.

In the end, you can’t tell people how to live their lives, but you can have boundaries and you can have certain areas of koala habitat, core habitats, that are sacrosanct and should never be developed.

Dogs don’t help his koala-ty of life.

I think that it is just a given that we will have to constantly find creative solutions to protect our wildlife. One thing’s for certain — there are no easy solutions.

Today I’m back on the road, driving from Pottsville

to Walgett in central western New South Wales. We have a field team doing work for our Koala Habitat Atlas project to map koala habitat at a scale that planners can use to make the decisions they need to make for koala conservation.

I drive from coastal, green New South Wales over the Great Dividing Range and west toward Walgett and Lightning Ridge. Lightning Ridge is an opal mining town and like many country towns is isolated by distance. The Olympic torch passed through Lightning Ridge a few weeks ago and by all accounts it was the biggest event to hit the town in decades!

You see a big change in the country as you cross the Range and reach the inland where it’s drier and the country is harsher. It has been so degraded since the time of white settlement, mainly by clearing for agriculture. The contrasts are startling — so much beauty and so much degradation. It’s hard to comprehend and digest it all emotionally. I love this country and it makes me sad to see what has happened, but I am also full of hope for the future, hope that there are solutions to the problems faced by koalas and this land.

Talk to you tomorrow.

Thursday, 14 Sep 2000

WALGETT, New South Wales

I had much to contemplate today during a long drive. On Monday, a letter arrived which has preyed on my mind. It contained some poignant photos of three koalas that had died in a tree outside a property in Victoria, a southern Australian state. The land around this woman’s property has been cleared for many years and a 300-year-old River Red Gum (a eucalyptus) was the only tree the koalas wanted to feed on. She rang me several weeks ago telling me that the koalas had been living in this tree for years and that the tree was now nearly out of leaves.

Two koalas in the dead tree.

What I find amazing is that there were other trees nearby which she had expressly planted for koalas, but they wouldn’t touch them. Why? Who knows, but it shows how complicated restoring land can be. It makes me wonder about the long-term implications of clearing land in this country and losing native seed stock. I’m not sure whether the trees that were planted were cultivated elsewhere, but it is really worrying to think that there was the right food there but for some reason the koalas would not eat it.

This woman knew that the tree was dying and the koalas were dying. She was incredibly distressed and had contacted various government authorities to try to get someone to help. Sadly, koalas are seen as a pest by government departments in Victoria and no help was offered, other than to shoot them. I rang a local department head myself and asked him to do something to help, but all he did was suggest that someone could come and move the koalas — at a cost of $300.

This koala died soon after the photo was taken.

Eventually nature took its course and the koalas dropped from the trees and died. The koala in this photo, which died a few hours after it was found at the base of the tree, looks so innocent and vulnerable. I feel very angry that this wonderful animal had to die like this, not because it had done anything wrong but because of 200 years of land degradation in Australia.

The face of this koala reminds me of a gorgeous children’s book about Australia — The Magic Pudding. The author, Norman Lindsay, a conservationist of his day (the movie Sirens depicts his life), had koala characters called Uncle Wattleberry and Bunyip Bluegum. These characters were brave, intelligent, humorous, and represented everything Australian. Norman Lindsay would be shocked to see the face on this dying koala.

Uncle Wattleberry and Bunyip Bluegum.

It’s hard to comprehend that people can see koalas as pests, but that is because in some parts of Victoria and South Australia there are isolated patches of habitat where koalas have eaten out the food resource and killed the trees. Many people, including some scientists, want to kill the koalas, but the Australian Koala Foundation has opposed this. It is our view that there are not too many koalas; rather, there are too few trees for them to live in.

Farming practices designed in Europe were introduced to Australia by our first settlers and they are not suited to our fragile continent. Well over 80 percent of Victoria’s original vegetation has been cleared. What remains is degraded farmland, small isolated patches of forest, and an increasingly modified forest system where native forest is being logged and replaced by plantations.

In addition to the land-clearing, koala populations were decimated by the fur trade in the early 1900s. It’s estimated that up to 10 million koalas were killed throughout Australia, and they were completely shot out of the state of South Australia. That seems amazing today when we estimate that there are less than 100,000 koalas left in the wild!

The problem of overcrowded habitats began when concerned authorities took small groups of koalas to islands in the hope of protecting them. Safe from the fur hunters, but unable to escape their island homes, these koalas increased in number, and in 1923 wildlife authorities in Victoria began translocating animals back to the mainland. Since then approximately 15,000 koalas have been moved to restock remaining habitats in Victoria. Remember, much of Victoria’s original forests have been cleared, and the remaining forests are now almost full of koalas.

The authorities say this is a successful wildlife management story, but we don’t quite see it this way. The government officials who are involved in these translocations are overwhelmed with their management responsibilities and can often see the koalas as pests. They even call them feral, a term used to describe introduced species. This is of grave concern to me. It would be like wildlife officers in the United States seeing the bald eagle as a feral animal. Unthinkable.

The problem is not going to go away and the AKF is constantly thinking of ways to help the government solve these problems long term, but they will not listen.

So, it is time for us to honor the koala (and all our indigenous flora and fauna). It’s time for a National Koala Act. And Koala Habitat Atlas maps to show where viable habitat remains and what needs to be protected. Which reminds me … that’s why I’m in Walgett. See you tomorrow with information on our mapping.

Friday, 15 Sep 2000

WALGETT, New South Wales

I’m here with our fieldwork team, which has been gathering data to compile a Koala Habitat Atlas for the Walgett Shire (like a county) in central western New South Wales. Walgett is about a 12-hour drive southwest of Brisbane — it’s a vast area of over 3,600,000 acres with highly fragmented habitat. It’s great to be in the “Aussie outback” and we’ve seen kangaroos, emus, parrots, sheep, clear skies, opal mines, koala poos, and dusty roads. We’ve got a koala keeper from the San Diego Zoo helping us and I think he’s had a great time.

We saw a flock of red-tailed black cockatoos flying overhead in pairs, which was an incredible experience. There must have been 1,000 of them and it’s good to see them, good to know they’re still here. All cockatoos, in fact most Australian wildlife, need hollows to have their babies. Hollows in eucalyptus trees can often take 100 years to develop.

Former koala habitat cleared for agriculture.

There is such a large contrast between seeing all this wildlife and seeing the devastation of cleared bushland. In some places there is a lot of vegetation, but in others the land is cleared as far as the eye can see.

We’ve also found contrasting views in the people we have met. Some are really friendly and interested to hear what we’re doing — they want our data to help them manage their land. But others are distrustful of us and defensive of what is on their land. There is a chasm between the city and the bush in Australia, especially now that land-clearing is a hot issue. People in the country don’t want city folk telling them what to do with their land. They’re feeling uncertain about the future, both in terms of their ability to survive economically and because there is international pressure to curb land-clearing and they believe that impinges upon their “rights” as property owners.

And koalas and their conservation are entwined in all this.

The koala is affected by urbanization. It is affected by agriculture. It is affected by extraction industries like sand mining and forestry. The logging of native forest can affect koala populations, but perhaps of more concern long term is the converting of native forests to plantations. Koalas can’t survive in monoculture plantations. Nor can many other species.

But it’s not always the farmers or loggers or miners who are to blame. We are all consumers and the demand for products like paper and food is causing forests in this country to be cut down at a rapid rate. So what to do?

Who could say no to these faces?

I think that the koala is a powerful symbol for conservation and a great teacher. It has the potential to teach us how to better manage our land and our forests, to teach about recycling, sustainability, and many other things. It is far easier to explain to people why they shouldn’t cut down trees if they think that something as cute as a koala could be affected.

The landholders in Walgett are ordinary human beings like you and me. A lot of their traditional farming practices are unsustainable, but it takes many years for people to change and do things in a new way. These farmers may be under pressure because market forces are squeezing them to produce their milk or their meat or their grain for less and less money so that people in the city can buy cheap products.

This is why we are mapping, to try and fit both farming and koalas together sustainably. It is not easy. Until we have information that identifies our biodiversity, including koala habitat, it will continue to be eroded by continual human pressures. This is not new, everyone knows it, but I am always so frustrated that mapping is the last thing that is done.

We need a bird’s eye view of where koala habitats are at a scale that people can use to plan for the future, be it for housing or cattle farming. We need to know how much habitat is enough to sustain koalas, while taking into account the land-use requirements. We need maps across the entire country like the ones we are producing for Walgett. Producing them costs time and money, but it’s an issue of national significance and worthy of the government’s support.

Our government doesn’t have any maps that in my opinion are good enough to protect our biodiversity. They would argue that mapping at the scale necessary is too expensive. But with the koalas contributing an estimated $1.1 billion per year to Australia’s economy through foreign tourism revenue (and that figure is expected to rise to $2.5 billion this Olympic year), how can they say it is not cost effective? It would only cost a fraction of that to map the entire range of the country’s koala habitat.

I used to think that the Australian Koala Foundation could map the whole koala habitat on the east coast of Australia. Currently we have mapped about 8 million acres. We still have 2.5 million square miles (yes, that’s square miles, not acres) to go, so we are looking for cheaper and more cost-effective ways of mapping. We have even used remote sensing to identify single eucalyptus trees. Over time we will convince the Australian government to map our way. It is too big a job for a small organization like ours, but we will show them how to do it.

If the koala cannot get our government to act responsibly, then no other animal will be able to do so. The koala is loved by millions around the world. It doesn’t hurt people. It doesn’t eat crops. It is a powerful symbol for conservation that can move people to action.

Wacky Wazza.

This is my last day writing to you, so before I go I want to paint a picture of Australia for you. I want you to know that it is a wonderful and exotic place. Please come and visit us — and meet blokes (guys) like Wazza.

Wazza contacted the AKF a couple of years ago wanting us to help him save a platypus habitat near Mackay on the central Queensland coast, because he was sure that the plight of the koala was linked in some way. Wazza was incredibly disturbed by the fact that a new dam was going to be built for sugar cane farming and that it would affect his beloved platypus habitat, as it had already destroyed koala habitat in the past.

Wazza’s house at Finch Hatton Gorge.

For years, I kept saying,”No Wazza, I cannot come. I have enough problems with koalas, I cannot add platypus.” But eventually I did go, and I found that Wazza was a real character, living an idyllic life at the romantically named Finch Hatton Gorge. (Yes, it was named after that guy in Out of Africa.) Although Wazza couldn’t show me any koalas, what my trip did give me was further knowledge about poor land use, poor water use, and the fact that there is no overview of what’s happening to those precious resources.

Mackay is a sugar growing town and almost the entire surrounding fertile Pioneer valley has been cleared to the water’s edge for sugar cane. The river flats would once have been wonderful koala habitat, but now there is barely a tree left standing, and as a result there is erosion of topsoil which is even affecting the Great Barrier Reef . When the tropical summer rains come, the topsoil from the cane farms washes down the river to the sea and settles on the coral, affecting the marine environment.

Walker walking.

Wazza, like many other great Australians, has helped teach me about the complexities of managing land. When you look at the photo of Wazza, picture him living in a bush camp, cooking over an open fire, toast and tea for breakfast, a goanna (big lizard) hanging over his tin roof that “smiles” at him in the morning, and most importantly a wonderful bird called Walker. He is so named because he cannot fly (he has beak and feather disease). He’s a featherless sulphur crested cockatoo. Some would say he looks like a small chicken with no feathers, but I would not say that in front of him. Wazza and Walker live in harmony in the bush. Walker can whistle all of Tequila Sunrise, but he expects the visitor to sing the final Tequila!

Wazza and Walker are always present in my mind. They represent everything Australian to me, although most of us urban dwellers would never have the chance to live as they do.

I will do everything I can while head of

the AKF to protect areas like the Finch Hatton Gorge forever. No amount of money made from selling sugar could ever make up for the tragic loss of the habitats in that Gorge.

I have loved writing to you and I thank you for wanting to know more about Australia. Tequila!

(If you’d like to get in touch with us at the Australian Koala Foundation, please email akf@savethekoala.com.)