Tony Rose is founder of the Bushmeat Project and director of The Gorilla Foundation‘s Wildlife Protectors Fund, a nonprofit organization working to influence positive shifts in conservation values and conservation practices in equatorial Africa.

Monday, 28 Jan 2002

HERMOSA BEACH, Calif.

The first question that must be answered in any self-examination is, “Where am I?”

The air is clear and crisp, high white clouds drift restlessly over a sky-blue sea, verdant cliffs rim the bay to the north and south, and where the noonday sunlight touches down, an explosion of silver shimmers from shore to horizon. This could be Cameroon, and I could be standing on the balcony outside my room at the Atlantic Beach Hotel in Limbe Town.

But I’m not in Cameroon. I’m in California, looking across the Pacific Ocean from my Hermosa Beach home on the south shore of Santa Monica Bay. Physically, that is.

If I were here in mind and spirit, then I would not be at the computer writing. It rained yesterday, and today I can see from Catalina to Malibu, and all the islands between. This is the kind of day when a man of nature ties on his hiking boots and takes off for the hills of Palos Verdes. Or pulls on shorts and sandals and settles in at ocean side with the pipers and gulls. Alas, not I. Not today.

I started my day at 6:30 a.m. with a call to London. Finished two cups of coffee sorting out the FedEx delivery of a book manuscript — and thought about the Thames. Remember how Joseph Conrad started Heart of Darkness; how his narrator, Marlow, began his tale at anchor on the Thames river where he had boarded ship after ship and drifted into uncharted waters seeking adventure, riches, power, meaning? The afternoon had been pleasant enough for Marlow and his friends, but no matter what appeared in daylight, the darkness was there in London, as it is in the Congo, as it is in Los Angeles.

The horror! The horror! I went to Cameroon in 1996 to meet Karl Ammann and learn about the plight of apes and people in equatorial Africa. Since then, no matter how brilliant the sky in whatever part of the world I travel, I experience darkness.

Ammann is the tireless conservation activist who exposed the bushmeat crisis to the world. Within a few hours of our meeting, he had us racing on motorbikes across Bertoua, capital of Cameroon’s Eastern Province, searching for a baby gorilla being held by a meat salesman. Inside a somber mud walled home, I sat on a plush red velvet sofa and held a soft, frightened young gorilla in my arms. The next day she was gone, spirited off before we could organize the gendarmes for a confiscation. By now she is dead. And so is the meat salesman.

The gorilla died of terror and loneliness, as do most infant apes who have witnessed their mother being butchered in the rainforest and cooked for sale in the cities. The man died of AIDS — another all-too-common fate for the people of Africa. Both died young. The horror!

The apes are being extinguished faster than the people. My life is committed to saving them, and their rainforest homelands, from becoming just another commodity in the global marketplace. To do this, we must save the African people too — for they too are being consumed as an expendable resource for the rich and powerful. That is what my manuscript is about — the one that is stuck in some delivery truck on a dark side street of London.

I am certain that tomorrow the package will be delivered and Karl and I will talk about what is needed to complete the second draft. I am not so sure about the deliverance of the animals and people of Africa. They may not get a second chance.

Outside on my balcony, dark clouds are circling in from the southwest. The ocean is gray, and churning. Too late to take this day off. Too much on my mind anyway. Of one thing I am certain: Tomorrow will bring its share of darkness.

Tuesday, 29 Jan 2002

HERMOSA BEACH, Calif.

Hail fell last night in Hermosa Beach. Ice sizzled in surf, pocked the sand, and tangled in my hair. A two-minute winter, followed by clear skies. That’s what we get here in sunny Southern California — pocket-sized cold snaps and perpetual spring. Or that’s what we get so long as the greenhouse effect and the ozone hole don’t melt the polar icecaps and reduce salinity in the deep sea conveyor belt that moderates ocean temperatures and keeps global climate in balance. If the meltdown happens, all bets are off. Real estate values will tumble like a tornado in Topeka. And this will be Kansas, Toto.

Catastrophic fantasies aside, it is another exquisite day, so far as I can tell at a glance. Of course a glance is all I get: Work prevails. I managed to reach Ammann at his flat in London this morning. The droll Swiss pessimist was in rare good spirits. He likes the manuscript — made my month. We now have a prototype coffee table book on its way to publishers in Europe, and ready to discuss with our donors in the U.S.

Imagine wildlife advocates and adventurers around the world giving friends the gift of a photo essay about African wildlife that tells the truth. Suppose Bill Gates, Tony Blair, and Pope John Paul flipped open this big fancy book with a brilliant mandrill on the cover and found themselves staring at a full color photo of a bloody butchered gorilla. That could start a revolution. And a revolution is what we need. A counter-revolution to reverse global greed.

Recent projections place the volume of bushmeat commerce in the Congo basin at two million metric tons — a $4 billion annual business, mostly illegal. The bushmeat trade became big business in the late 1980s, when the timber barons of Europe began to buy options on rainforests in central Africa. Pulling hardwood out of the wilderness is very profitable in countries where labor is cheap and government regulations are minimal. A constant and growing stream of men have moved into the forests, under contract to cut wood and transport it back to sawmills in the cities. Many have brought wives and children, or found them in the villages. Roads and logging towns have sprung up in pristine wilderness areas from Cameroon to eastern Congo (DRC). The result: a commercial and cultural revolution.

The forest has become a marketplace. Where bird calls and the chatter of monkeys were once the loudest sounds of the day, the roar of chainsaws and the explosion of falling timber are now heard from sunup to sundown. At night, gunshots and radio drown out the cries of sloth and civet cat. With the subduing of nature, there comes a subverting of culture. Cash corrupts community and seduces local leaders to serve outsiders instead of their people. For a small pension, the mayor will look aside when loggers and hunters cut protected trees and kill endangered species. The profit motive overwhelms ecological interests. To increase their margins, timber companies don’t provide poultry or beef to their workers, but instead encourage bushmeat business. The traditional hunting grounds are being converted to modern harvest fields to feed a captive market of hungry loggers and their families.

It is time that people around the world confront this tragic situation and help to stop it. The loggers and urban elite of Africa won’t become vegetarians anytime soon, but they can be asked to stop paying a premium to eat vanishing species. Urban Africans, from the business sector to the parliament, are demanding meat from apes and other endangered animals for their feast tables. In doing so, they are setting aside both ethics and the law. There is nowhere in the world where killing and consuming apes is legal. But the laws are on the books, not in the values of many African people. Even the clergy transgresses.

Last year a colleague of ours showed up at a party for a visiting Catholic bishop and found gorilla meat on the table. This was in eastern Cameroon, just a few miles from a gorilla protection project we helped develop. The local priest removed the gorilla steak at once, but the damage had been done. His call for bushmeat had produced what local hunters considered a delicacy. The result — two dead gorillas — was an embarrassment to the bishop, but he showed no signs of remorse for the apes. Ape or antelope, pig or porcupine — it’s all meat in much of equatorial Africa.

How can we expect anything different? We set the example. It is northern consumer societies that have set the stage for eating apes. The prevailing message we send around the world in our entertainment and advertising is, “Consume goods, spend money, live in luxury and comfort! That’s what life is for.” Euro-Americans are the mouth of modern civilization, consuming 80 percent of the gross world product. It’s not surprising that the people of Africa who aspire to an affluent lifestyle are feasting on their natural heritage.

The horror starts here, at home in affluent America and Europe. And I am part of it, living in this wonderland at the edge of the Pacific Ocean where the greatest challenges are a two-minute hail storm and crossing a busy intersection at rush hour. I guess that’s why I spend sunup to sundown in my office, and barely allow myself a sideways glance at the sea. I’ve paid my dues for the day, trying to save apes. Just in time for sunset.

Wednesday, 30 Jan 2002

HERMOSA BEACH, Calif.

Well — now that the bushmeat book is in the hands of publishers, I can move on to the next project. I reached Penny Patterson at the Gorilla Foundation research station in Northern California during lunch. She was with her primate friend Koko, and they were building snow gorillas.

“Koko loves this! I think she likes eating snow cones best,” Penny said.

I asked Penny to say hello to Koko for me. Just then I heard a crunch, and after a pause Penny explained that Koko was throwing snowballs at her. Clearly this was not the best time to talk about our writing project. But we did manage to agree that on Friday we would begin discussions with Ron Cohn about selecting photos for Michael’s Dream.

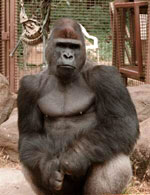

Penny and I are writing a photo-based story about Michael, the silverback who joined Koko as a youngster at Stanford more than two decades ago when Penny and Ron were in the early stages of their gorilla communication research program. Michael was a remarkable being, memorable as a fine artist, music aficionado, and the most loyal and protective friend to all who lived and worked with him.

Michael died a sudden death just after his 28th birthday, in April 2000. His heart gave out, as happens with many male gorillas in captivity in the prime of their lives. Michael was a superb example of the great silverback, with a picture-perfect muscular body. Nonetheless, all his life he felt threatened by unfamiliar humans. When strangers appeared in his territory, he put on fierce displays, banging walls and grunting in anger. We are convinced that he died because the fear instilled in him as a baby made him work too hard to protect his friends — Koko, Penny, and Ron. He did not want to lose them, the way he lost his first family in the forest. Michael was a bushmeat orphan.

One morning when Michael was still young he awoke in a state of extreme distress. Penny sat calmly with him while Ron set up the video. They talked in the gorilla language of signs and gestures, and a story unfolded. Michael told Penny of the dream that he had that night. It was the story of the morning in the rainforest when he had been captured and his family had been slaughtered. Michael remembered and described the horrid sound of gunshot, the cries of pain, the terror and trembling, the bright red blood, the shock, the struggle and submission as strong arms carried him off while his mother lay dead in the bush.

Imagine witnessing your mother and father being shot, killed, and butchered by poachers. What would it be like, at age three, to be captured by the killers, taken from your rain forest home, tied to a post in an alien village, stuffed in a metal box, bounced in darkness by car and airplane for days on end, and held in barren isolation cages for months? How would you feel about the people who did this to you, to your family, to your life?

Michael overcame his inner terror enough to trust many people. On quiet days the great silverback could be seen relaxed and listening to Pavarotti singing favorite arias. He loved to play tag with human caregivers, and with his dog friend, Apple. Michael so enjoyed playing with Apple that he insisted on rendering his image on canvas. The painting “Apple Chase” captures the colors and movement that a sensitive silverback gorilla experiences, painted by the gorilla’s own hand.

I was lucky enough to visit Michael and be accepted by him. It was a profound experience to look into his dark eyes and imagine the memories he had. His is a heroic journey — from the rain forests of Africa to the redwoods of California, along the way overcoming profound childhood trauma, spanning the gap between species, and becoming the protector of a community of fellow souls.

I have told the story of Michael’s dream to hundreds of people in African villages — poachers, village elders, students. They were all deeply effected. One wise old man exclaimed, “We cannot eat such animals that have memories and feelings as we do.” There are millions of people who need to learn this lesson. We have work to do.

So — back to it. There are at least another two dozen “conversations with Michael” that I must sort through tonight. Miles to go before I sleep …

Thursday, 31 Jan 2002

HERMOSA BEACH, Calif.

From a night of tossing and dark dreams, I popped out of bed at 5 a.m. with a mind full of unfinished tasks. Leave no Gestalt undone, or sleep will suffer. Trouble is, there is never closure on the work I do. So I wrap myself in a sarong and stumble in the darkness down the hall to my office. A typical Thursday: pushing the emails out early, lobbing the ball into the other guy’s court before the weekend begins.

It is tough to manage projects on the other side of the world. Impossible, really. I should have been in Cameroon this week, but couldn’t pull it off. So now I have to do the best I can with emails and phone calls, and plan to spend twice the time there when I go in May. Luckily, we have an experienced professional taking on the development of our Conservation Values Education program there. Penny Fraser’s email from Yaounde this morning updated me on our progress, and on some of the problems.

CWAF Director Chris Mitchell acclimates a gorilla orphan to his new home.

Photo: Tony Rose.

Our partner, Cameroon Wildlife Aid Fund, has made tremendous strides. This week, CWAF held a conference on Environmental Education at the new education facility at the Yaounde Zoo and Wildlife Center. The Cameroon Ministry of Environment and Forests (MINEF) contracted CWAF Director Chris Mitchell to help manage and improve the old Yaounde Zoo some five years ago, and the transformation has been extraordinary. Decrepit, dungeon-like cages have been replaced by fine outdoor enclosures where gorilla, chimpanzee, and drill orphans can regain confidence and health in carefully structured primate social groups. The animals are cared for by local men and women who develop strong bonds with their wards. And now, with the opening of a teaching facility, the understanding and empathy that CWAF staff members are developing for endangered wildlife can be transmitted to thousands of Cameroonians.

That is the main emphasis of our work in Africa: to deepen local people’s feelings for the wildlife around them. We focus on apes and other primates because they are most similar to people: They evoke the sense of kinship that will turn consumers and poachers into protectors of wildlife. The Wildlife Protectors Fund was established at the Gorilla Foundation as a focal point for this effort.

Psychologists began to study ape communication decades ago. The breakthrough came with the recognition that great apes use gestures and postures to talk to one another. Could they learn to talk with humans, using sign language? Penny Patterson and Ron Cohn, Roger and Debbie Fouts, Sue Savage and Duane Rumbaugh, and Lynne Miles proved that gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans could learn hundreds of symbols that allowed them to share their desires, their feelings, and their dreams. Apes named Koko, Washoe, Kanzi, and Chantek became famous for crossing the species barrier and exposing our hominoid kinship.

The stories of these communicating apes are being translated into the languages of the people who live in and around primate habitats. Already we have found that the French version of Koko’s Kitten has created positive attitude changes among the thousands of Africans who have read and discussed the story in our education programs. To learn that a huge gorilla can adopt and cherish a tiny kitten shifts people’s perceptions of these apes from savage beasts to sensitive beings.

We are anxious to publish the story of Michael, and inform Africans of the unforgettable trauma that poaching causes for the families of apes killed for bushmeat. That’s what I was supposed to be working on this morning, until other urgencies took over.

Gorilla orphans bond with their caregiver.

Photo: Tony Rose.

To work in the conservation arena is to live in a relentless cacophony of crises. Not only are forests being cut down and wildlife slaughtered. Not only are ape orphans emerging from the bush on death’s edge far faster than we can find people and funds to recover and rehabilitate them. Not only are consumers tasting their first ape meat before we can ignite in them a deep caring for kindred life. But the devoted conservationists already at work in the field are themselves falling prey to the dangers of working for the wild.

I just called a compatriot in Africa only to discover that he has been airlifted with his wife to Europe and is sitting at her bedside in an intensive care unit. This is the latest in a constant string of tragic challenges. Last month, one of our staff spent a week in a British hospital being treated for parasites brought back from the bush. Last summer, one of our program leaders finally threw in the towel and took his family out of Cameroon to seek an assignment in a safer place. Last spring, a bright young field researcher was killed in an auto accident on a narrow dirt road in the rain forest.

The stress and health risks are formidable. But if it seems tough for expatriate conservationists who leave home to work in the bush, it is far, far worse for the average African. They have nowhere else to go. They must face the downturn of their economy and the upsurge of disease and chaos with no exit.

There are success stories, but they are few and far between, and the triumph is always tenuous. My dear friend Joseph Melloh, who has transformed himself from gorilla hunter to wildlife protector, seems to be hanging in there. I think he is out on an assignment, but I’m not sure where. War zone? Hunting camp? Ebola clinic? I worry about him. It’s too late to call anyone over there who might know how he is. I’ll save that for tomorrow.

Friday, 1 Feb 2002

HERMOSA BEACH, Calif.

I began the week asking, “Where am I?” It is the place one perceives and experiences that circumscribes one’s identity. Physical surroundings don’t always inform a person’s thoughts, feelings, or actions. And it is our mind and manners that determine who we are.

For me, most daylight hours are spent in Africa — mentally. So at these times I am Tony Rose, the conservation psychologist. This is true when I am in Cameroon, and when I am in California. It takes great discipline to pull myself back to Hermosa Beach at the end of the day: to become the father, husband, friend. Usually, I do this by standing on the balcony and watching the sun set into the Pacific Ocean. There, the dark continent is replaced by a darkening sea and sky.

This morning was different. Before I could finish my first emails — to Ron Cohn in Woodside and Karl Ammann in Zurich — a call came from my wife, Annie. “Today is Celeste’s birthday celebration at Via Pacifica! Bring your camera — now!”

Imagine the shock. Take yourself out of the rainforest, now, and come to school. Stop pondering the lives of talking apes and ex-gorilla hunters. Participate in the lives of your children, your community here at home. It was hardest to stop thinking about Joseph. He is the Bantu man whom Karl and I have been supporting for over five years in his quest to become a conservation worker. Today, I had hoped to outline a plan for writing the story of Joseph. A copy of my first article about Joseph, “On the Road with a Gorilla Hunter” (download a PDF version), still sits here on the desk. Beside it are photos of Joseph’s three boys: Karl, Anthony, and Pious.

Rose’s raison d’etre.

Photo: Tony Rose.

It was a painful moment, like birth. I shut down AOL, picked up my Sony digital, poured a fresh tumbler of coffee, and trudged out the door. Imaginary aromas of red clay and gorilla musk vanished, replaced by sea salt and fresh-cut grass. Driving along quiet streets past rows of high-class homes, I set myself in order. Sorted my priorities. I was going to see my child; my reason for being who I am.

I work to save Africa because of my daughters, Celeste and Gabriela. I labor in distant climes for my son Josh and his son Noah. They must know the world as it was, the way it was created. A wild world where the synergy of all living forms and forces prevails. They must transcend the human construction, reach beyond this faulty landscape of square corners and stoplights; see through plastic heroes and dull aspirations designed by men who have never slept in starlight.

My children, your children, all the children of the city must meet Joseph’s children, and all the children of the forest. We must take ourselves and our children out of this urban exile and become immersed in Eden again. That is how we shall be redefined. Only in wilderness can we discover the essence of being human. Only in Africa, in all the wild Africas of the planet; only in the birthplace of the human soul, can we become whole.

At the school, I watched the celebration. The children sang birthday songs in two dozen languages from all the continents of the world. I joined in the ones I knew — Spanish, French, Swahili, Indonesian, English. Celeste sat in the birthday chair and was lifted high in the air by her classmates, a ritual of trust and support. She then gave her gifts to the school: books about nonviolence and peace in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. There was a melancholy tone to the event, especially for the older children whose birthdays mark their transition to more adult responsibility. I acknowledge their passage.

Sunset in Hermosa Beach.

Photo: Tony Rose.

It is vitally important that I be here, now, for my children. To take them where they are, enmeshed in their own world views, is the way to know their hearts, their hopes, their hurts. That is how I will connect with them — in their place. From that connection, as they trust that I respect who they are in this temporary constructed world, we shall move together into the world as it has always existed in eternal time.

I work to save Africa so my children, all our children, can discover where we were born and where we will die. Once we find this place of origin and destiny, we will know who we are and how we can make peace in the world.