By Janet Larsen

In recent years weather events have whiplashed between the extremes of heat and cold, flooding and drought. Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases—largely from the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas—have loaded up in the atmosphere, heating the planet and pushing humanity onto a climatic seesaw of weather irregularities. High-temperature records in many places are already being broken with startling frequency, and hotter temperatures are in store. Without a dramatic reduction in fossil fuel use, we will veer even further away from the “normal” temperatures and weather patterns that civilization is adapted to.

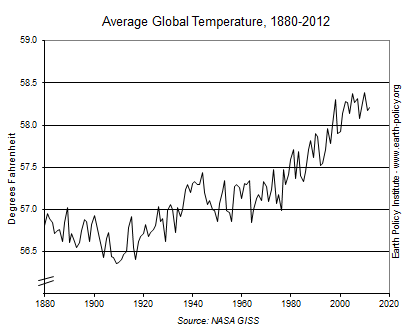

The world has warmed by 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit (0.8 degrees Celsius) since the Industrial Revolution, with most of the rise in temperature coming since the 1970s. Such rapid warming is unprecedented over at least 20,000 years. The average global temperature in 2012 was 58.2 degrees Fahrenheit (14.56 degrees Celsius). This sets it among the 10 warmest years on record—all of which, according to NASA data dating back to 1880, have occurred in the last 14 years. (See data.)

The two headline-dominating weather events of 2012 both occurred in the United States: the intense summertime drought and heat that baked the country’s midsection and Superstorm Sandy, which clobbered the East Coast in late October. Overall, 2012 was the hottest year in U.S. history, topping the twentieth-century average by more than 3 degrees Fahrenheit.

After a winter that never seemed to take hold over much of the United States&‐with snow coverage across the lower 48 states the third lowest on record—summer-like weather arrived in March. Close to 15,000 new high-temperature records were set. Thus began the warmest spring in U.S. history, setting the stage for further high temperatures and an epic drought. July 2012 was the hottest month ever in the continental United States, according to the National Climatic Data Center. A third of the U.S. population witnessed summer temperatures of 100 degrees Fahrenheit or higher for 10 or more days. At its peak, drought covered nearly two thirds of the country. Power plants shut down because of the lack of cooling water. Low water levels disrupted Mississippi River barge traffic. Crops withered; corn yields in key producing areas were cut by a fifth or more. Purdue University economist Chris Hurt estimates the cost of the drought could exceed $75 billion. And with drought lingering into the new year, particularly in the Great Plains, the odds of a second year of harvest shortfalls are increasing.

The other most expensive weather event of 2012 was the opposite precipitation extreme: Superstorm Sandy. Sandy was number 18 of 19 named Atlantic storms in a season that began even before its official start, with two storms forming in May. After bringing heavy rain to the Caribbean and killing 72 people, Sandy merged with a winter storm, transforming into a meteorological chimera. Rather than travelling a more typical pathway out to sea, Sandy made an abrupt left-hand turn to make landfall on the U.S. East Coast. Fueled by high sea-surface temperatures and loaded with extra moisture due to warmer air temperatures, Sandy brought more than a foot of rainfall to parts of the mid-Atlantic region. Coasts from Maryland to Massachusetts were hit by a tremendous storm surge that in Lower Manhattan reached more than 9 feet above the normal high-tide level. In New York and New Jersey close to 100 people died, and more than a half-million homes were damaged or destroyed. Blizzards blanketed parts of Appalachia with the most snow ever recorded for a U.S. storm in October. Costs are still being tallied, but state governments report damages of $62 billion.

Some scientists propose that Sandy was pushed onto its unusual trajectory because of changes in atmospheric circulation caused by the loss of sea ice in the rapidly warming Arctic. As the Arctic’s reflective ice cover shrinks, more heat is absorbed, resulting in a smaller temperature differential between the North Pole and higher latitudes. This can cause the jet stream to slow down or become more wavy, stalling typical weather patterns and leading to prolonged extreme events. The regional warming is also accelerating ice melt on Greenland, which contains enough water to raise global sea level by 23 feet (7 meters). In late May 2012, southern Greenland reached a balmy 76.6 degrees Fahrenheit. In mid-July, 97 percent of its surface area showed signs of melting.

The year was exceptionally warm in Canada, where summer 2012 was the warmest on record. For Russia it was the second warmest, just behind summer 2010, when Moscow was smothered by heat and choked with smoke from rampant wildfires. In both years crops suffered, contributing to a jump in food prices. In France, an unusually late and sudden heat wave toward the end of August broke the high-temperature records set during the 2003 heat wave that killed nearly 15,000 people nationwide.

Models predict that with increasing global temperatures such heat waves will come more frequently and with greater ferocity. A 2013 study published in Climatic Change notes that already five times more high-temperature records are being set globally than would otherwise be seen in the absence of climate change. This played out in 2012 in the Middle East and North Africa, when Jordan suffered through heat more than 16 degrees Fahrenheit above the normal maximum in June and July. Morocco set a new all-time high in mid-July. Later that month, Kuwait hit 128.5 degrees Fahrenheit, likely the highest temperature ever recorded in Asia.

The deadliest weather event of 2012 was the category 5 Super Typhoon Bopha, which hit Mindanao in December with torrential rainfall and wind speeds of 160 miles per hour, leading to 1,900 dead or missing and 700,000 homeless. This was the second year in a row a major storm made landfall in the southern Philippines.

China also sustained major weather damage in 2012, with losses from flooding, typhoons, and other severe weather exceeding $29 billion, according to reinsurance firm Aon Benfield. In the spring, most parts of the country were hitting temperatures 9 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the 1961–90 average. In July, a heavy downpour flooded Beijing with more rainfall than in any one day in over 60 years of records. On the other end of the spectrum, drought affected more than 9 million people and damaged 2.5 million acres of crops in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces earlier in the year.

In northeastern Brazil, the first half of 2012 was extraordinarily dry. More than 1,100 towns were affected in the worst drought in 50 years of data—quite the contrast to the heavy rains that hit the upper Amazon Basin in northwestern Brazil and Peru and led to record-high flow in the Amazon River. August 2012 brought extreme rain and flooding to central and northern Argentina, with rainfall in some places double the previous records, based on statistics kept since 1875.

Climate change tends to bring more high temperature records than low ones, but it also can bring surprises like the cold snaps that bookended the year in Eurasia. In late January to mid-February, parts of central Europe did not get above freezing for 20 days straight, twice as long as the February norm. Then at the close of the year, a dip down in the polar jet stream returned frigid weather to Russia, northern and eastern China, and northern Europe. Just a few months after Russia’s second warmest summer, December temperatures plunged to the lowest level in the records kept since 1938. Residential electricity consumption in Moscow soared to an all-time high as the mercury dropped to –22 degrees Fahrenheit. In eastern Siberia, it was –76. More than 100 people died and over 800 were hospitalized from the cold.

Down under, it was a different story. The start of 2012 looked a lot like 2010–11 in Australia—its wettest two-year period in over a century of recordkeeping, which came on the heels of a decade-long epic drought. But then wet turned back to dry, and cool turned very hot. A heat wave that began in late December was unusually long and widespread, with high-temperature records set in every state. In January 2013, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology added a new color to its maps to portray the scorching temperatures, extending the scale that had topped out at 122 degrees Fahrenheit to 129 degrees.

These are some of the early signs of a new, hotter temperature regime. The world’s governments agreed in principle in 2009 to stop global warming from exceeding the “dangerous” 2-degree-Celsius (3.6-degree-Fahrenheit) rise in temperature. But as fossil fuel emissions continue to rise, the chances of staying within that 2-degree window are disappearing. The more the world heats up, the harder it will be to avoid off-the-charts weather catastrophes.

# # #

For a plan to stabilize the Earth’s climate, see “Time for Plan B.” Janet Larsen is Director of Research at Earth Policy Institute.