The cermonial urban-turbine installation.indigo12west.comTwo weeks ago in Portland, Oregon, a new 23-story building added something you don’t usually see in an urban setting: a series of four Skystream wind turbines, with a total capacity of 9.6kW.

The cermonial urban-turbine installation.indigo12west.comTwo weeks ago in Portland, Oregon, a new 23-story building added something you don’t usually see in an urban setting: a series of four Skystream wind turbines, with a total capacity of 9.6kW.

There are several reasons why wind turbines are a rarity atop highrises — beyond the obvious one: our power infrastructure makes changing from traditional sources of electricity difficult, expensive, and seemingly unnecessary. (As long as you can convince yourself that the planet isn’t really warming and that 15,000 Americans don’t die prematurely each year from breathing in filthy air from coal-fired power plants, and that the price of energy is going to stay stable and … you get the idea.)

Wind power in an urban setting comes with its own set of challenges.

A natural lack of regular winds forceful enough to generate meaningful amounts of electricity.

Most “wind farms” are located in areas with high, steady winds and use giant turbines. In fact, the trend has been to build larger windmills capable of generating ever more electricity.

In 2006, Technology Review ran an interesting piece about plans for a new turbine with a rotor with a 140 meter diameter.

Sometimes, however, smaller still is beautiful — and more appropriate.

So some manufactures, like the Flagstaff, Ariz.-based Skystream, have been building scaled down wind turbines like the ones on top of Twelve|West.

One advantage of the Skystream 3.7 is its lower wind speed requirement. With its 12-foot diameter, the rotor can begin generating electricity with winds blowing at just 8 miles per hour. It reaches peak production (2.4kW) at 29 mph and will continue to operate at winds up to 60 mph. (The Skystream 3.7 is built to withstand gusts of up to 140 mph.)

Wind flow in urban areas is disrupted by other buildings.

Placing the turbines on top of a 23-story building, and then mounting them on 45-foot poles puts the blades at an elevation of 82 meters (270 feet), high enough to escape the distortions of the surrounding built environment.

Still, critics of the project have said that the expense of putting the four turbines into operation outweighs the financial payback delivered in energy savings.

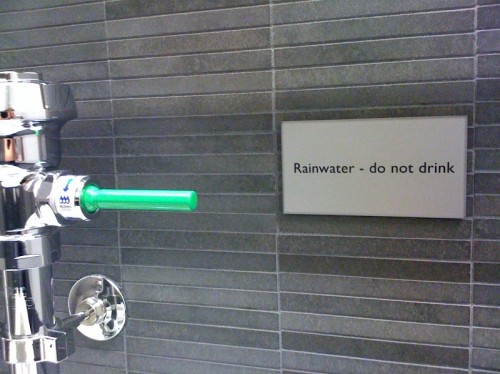

The building’s other eco-features include graywater in the toilets — leading to this helpful warning.But Robert Packard, a managing partner of the architectural firm ZGF, which occupies the lower four floors of Twelve|West and also designed the building, thinks those critics are missing the point. Packard told the Oregonian newspaper, “[We’re] trying something new. It’s not a gimmick. Not only are we learning, but we can share it with the world, add to the body of knowledge that’s out there.”

The building’s other eco-features include graywater in the toilets — leading to this helpful warning.But Robert Packard, a managing partner of the architectural firm ZGF, which occupies the lower four floors of Twelve|West and also designed the building, thinks those critics are missing the point. Packard told the Oregonian newspaper, “[We’re] trying something new. It’s not a gimmick. Not only are we learning, but we can share it with the world, add to the body of knowledge that’s out there.”

Kind of like when solar photovoltaic panels were just getting popular. Not every idea that worked well in the lab made it in the real (rooftop) world.

I’m hoping the information they get from the four turbines helps the shift from a fossil-fuel to a renewable energy economy. But I have to admit, just the sight of windmills spinning on urban rooftops — 20 or more stories up — has an appeal all its own.

Osha Gray Davidson blogs regularly for Grist and edits The Phoenix Sun, where this post first appeared in a different form.