A long time ago, when I first moved to San Francisco, I was walking through North Beach one morning, and I heard barking. Not dogs barking. Humans barking like dogs.

It got louder. Then I saw them: about eight people, in outfits that could sort of be described as dog outfits, if you were trying to make a dog costume out of things that you already had in your closet. They were pulling a shopping cart with a person sitting inside. “Mush! Mush!” the person in the shopping cart yelled. They were moving surprisingly fast. And then they were gone.

The people of San Francisco know how to make their own fun, from Carnaval in the Mission, to the Hunky Jesus contest that the drag nuns put on every Easter, to the interpretive dance that I saw some guy doing in the middle of traffic the night the Giants won the World Series.

So when I found out that the city had committed to spending $5 million to help the NFL throw a party by building a sportsball-themed city-within-a-city downtown, blocking off several blocks of roads and traffic for an entire week, the first thing I thought was: What? We’ve got a housing crisis going on! We’ve got a budget shortfall of $100 million! Now the freaking LA Times is making fun of what suckers we are! Trash from the fireworks display is washing up on the shores of Aquatic Park! The city attorney made Verizon take down a 10-story ad it put up on a skyscraper without permission, and now Verizon wants $2 million in compensation! We may never know how much the city is shelling out for this! And How did Condoleezza Rice get involved in this thing? Since when does she even know how to throw a party?

The second thing I thought was: I have to see this. That is how I came to visit Super Bowl City.

On the train ride over I wondered, dreamily, just what a Super Bowl City would look like. It sounded so ambitious. Maybe a fake city, with tiny houses made out of footballs? Maybe an enormous kiddie playground with a jungle gym made to look like an enormous Joe Namath?

My train arrived. I stepped off the escalator at the Embarcadero stop downtown and walked right into a group of people in orange, zip-up jackets and security clearance lanyards. They stood in front of what used to be an open street and was now a pile of barricades wrapped in plastic security netting. “Go left!” they screamed. “Go left go left go left!” I went left. There were more barricades and then, after a block, a security checkpoint, with a long line and a metal detector. Good thing I had brought a book to read.

After about 15 minutes of waiting, I cleared the metal detector and the bag search. I was officially cleared to visit Super Bowl City. This is what I saw:

Which is a courtyard made of beer cans. Inside, they are selling Bud Light for $8.

Here’s the sign on the beer cans:

Here’s how I could still tell that I was in San Francisco: As I walked past the beer cans, a security guard who had clearly been assigned to patrol them said, in a fake-panicked voice, “Don’t touch the beer cans!” and then laughed evilly like a sideshow villain.

Inside the courtyard made of beer cans is a fist made of beer cans, holding a football made of beer cans. It has a velvet rope around it.

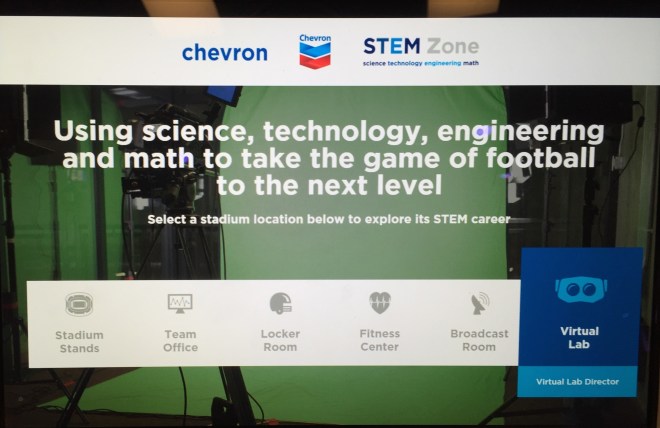

This was Super Bowl City. Nothing but a collection of advertisements for different brands (Levis, CBS, Verizon, the NFL, etc.) thinly disguised as either things to pose in front of or as “interactive educational exhibits,” like this:

I felt pretty great when I took the “stadium stands” quiz and correctly guessed that if the retractable roof on the Dallas football stadium is 300 feet wide, it has steel truss arches with a 1,290 foot span. But also: Who asks a kid that? Someone who has no interest in the delight of children, but is the person at the office assigned to write “content” for a pseudo-interactive exhibit that needs to exist so that the words “Chevron” can be printed really large across the facade. I am amazed that the city attorney only made Super Bowl City take down one (admittedly 1o-story) advertisement. This entire place is an enormous, thinly disguised ad hustle.

On my journey through Super Bowl City, I passed many, many places to buy beer and fried food. Including that blast-from-the-past, “Freedom Fries.”

Maybe they don’t mean those “Freedom Fries?” Because even the congressional cafeteria has moved on from France’s opposition to the invasion of Iraq. I would hope the NFL, too, is willing to let it go.

So here’s the thing: Super Bowl City is boring — it is, basically, a people corral for eating and drinking and purchasing NFL merchandise. But it is also pleasant. And this wouldn’t seem sinister, except that I’ve been here before. Many times. This is Justin Herman Plaza, named after the man who was in charge of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency from 1959 until his death in 1971. Herman was the man who, in the 1960s, led the demolition of much of the Fillmore — a then-thriving black neighborhood. In 1970, Herman was the guy who said, “This land is too valuable to permit poor people to park on it,” when a grassroots movement emerged in the city to stop the demolition of the I-Hotel, a residence hotel full of elderly Filipino immigrants, to make room for a parking garage.

I had a professor once who said, “When something doesn’t make sense in the present day, and you want to understand it, go back 50 years.” In the case of San Francisco, that is absolutely true. If you ever hear people complain that they don’t understand why San Francisco is so distrustful of new development, even in an epic housing shortage, tell them to go read up on their Justin Herman. Not long ago, I ran across a petition to rename the plaza after Maya Angelou (who grew up in the Fillmore). Unofficially, everyone I know calls it “Pee-Wee Herman Plaza,” and has for years.

I’ve never seen Pee-Wee Herman Plaza look as sparkling clean as it does right now, when it’s doing double duty as Super Bowl City. Because it’s a big, mostly empty pavilion — the kind that was so popular with urban planners in the ’60s and ’70s — people tend to just hustle through, instead of hanging out. Ever since I’ve lived in SF, homeless people have lived in the Plaza — sometimes tucked away in the shadows, sometimes right out in the open. Occupy San Francisco had its camp here — right where CBS is now, and right where, a few years ago, I saw a parkour class leaping over a row of people sleeping huddled together outside.

Reportedly, most of the people who normally live here have been pushed by police to a tent city underneath an on-ramp to the 101, in the closest thing the city still has to an industrial area. In the meantime, I’ve never seen so many police in one place since I covered a protest on Wall Street. Some of them are in regular police uniforms and wander around, smiling. Others, in what appear to be full SWAT team gear, stand stock-still in the shadows and wait.

The homeless enclave will be back, I’m sure, once Super Bowl City pulls up its stakes and moves on. And the NFL has brought something to the city — in the sense that, cutting across lines of class, race, and neighborhood, it has brought residents together in hating it. It’s given the city a break from thinking about what a harsh place it is to live right now, and a break from having to think about how we might change that. We could start by never hosting Super Bowl City again.