Jane Jacobs.

In two hours of wandering slowly down Broadway last Sunday, I heard about a solar installation over on FDR drive, the number of bird species that can be seen in New York City (roughly half of all that appear in North America), and an Astor Place riot sparked by two rival productions of Macbeth, one marketed to New York’s upper echelons, the other to its less savory elements. Along with a group of other sightseers, I gazed up at former tenements and butter and egg factories now converted into condos and office buildings. We talked about other neighborhoods we’d visited.

But one thing we did not do was talk very much about Jane Jacobs, her work, or her ideas. Funny, Jacobs was the reason we were all there.

This past weekend, in 85 cities around the world, there were at least 580 different ways to honor the legacy of Jacobs — writer, grassroots organizer, patron saint of city lovers everywhere. All of them involved walking — many of them took place under the umbrella of the Toronto-based organization Jane’s Walk — but the similarities pretty much ended there.

In New York alone, the Jane’s Walk website listed 65 walks to choose from. Jacobians could explore the West Village streets that Jacobs loved or that terror of all that is good in the world, the Atlantic Yards stadium, which some Brooklynites think is destroying their neighborhood. Another group toured the area around the Staten Island ferry terminal, not known for its urban vibrancy. Some of these walks involved detailed engagement with Jacobs’ ideas and their application to city-building today. Some did not.

Jacobs, for the uninitiated, lived for years in New York City’s West Village. She was a writer, community organizer, and sometime student, and in 1961, she published The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a treatise on the urban planning policies of the 1950s. She was not particularly fond of those policies, which favored cars and the razing whole city blocks. She was fond of dense, mixed-use neighborhoods.

These days, it’s impossible to avoid Jacobs’ legacy when thinking about cities. But it’s almost as tricky to pin down what, exactly, her legacy is. Great American Cities is long (458 pages) and, in places, boring. (Full disclosure: I’ve read about half altogether — definitely most of Part One, and sections of the other three parts.) Plenty of people who adore Jacobs haven’t read the whole thing, or any of her eight other books. She’s become, for many people, a stand-in for the idea that cities are awesome. If there’s some aspect of a vibrant city that you happen to like, well, you’re pretty safe asserting that Jane would have liked it too.

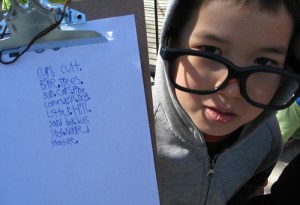

A youngster takes place in a Junior Jane’s Walk. We think Jacobs would approve of his list — and his glasses. (Photo by Spacing Magazine.)

Jane’s Walk began in 2007, when a group of Jacobs’ friends and colleagues led 27 tours around Toronto. The first year was wildly popular, and the number of walks has jumped every year since. “Walks are as varied as the people taking part,” the Jane’s Walk website says. They’re so varied that there’s a separate program — Jane Jacobs Walk, based in Utah, out of the Center for Living City — that helps coordinate walks on the same weekend. In the United States, at least, Jane Jacobs Walk listed options in more cities: places like Ogden, Utah, or Carthage, Miss., as well as major cities not on the official Jane’s Walk list, like Boston, Austin, Seattle, and Los Angeles.

In New York, the task of coordinating the volunteer-led walks fell to the Municipal Art Society (MAS), a stalwart of the nonprofit urbanism industrial complex. MAS has been in existence since before Jacobs was alive and sees itself as a convener of conversations about vital urban issues. “But you guys are big into Jane Jacobs,” I confirmed with Vin Cipolla, the president of MAS, when I caught him at the end of the walk he led on Sunday. Yes, he said, and called Jacobs “the most important urban planner in the world.”

Cipolla had led one leg of the walk I joined — the epic Broadway Baton, which started at 8 a.m. at 240th Street and proceeded, in two-hour chunks, the 14.5 miles down to Bowling Green, where the walk ended at 8 p.m. This particular walk was organized by artist Mary Miss and her staff. Miss is working on a project called “City as Living Laboratory: Sustainability Made Tangible Through the Arts,” in which she’ll put in what she calls “modest installations” — convex mirrors on lime green poles — up and down Broadway. Each one will draw attention to an aspect of the environment or infrastructure — a building that has a green roof, for example. The idea is to “have people be able to walk down the street and decode the city,” Miss said.

The walk itself served as a type of research for Miss. As we meandered down Broadway, artists, scientists, professors, and community activists served as guides. We walked close by the “super blocks” below Washington Square Park, extra-large city blocks created by Jacobs’ nemesis, Robert Moses, in a slum-clearing program. Washington Square Park was hugely important to Jacobs, and she led a successful community campaign to keep Moses from running a highway through it. Zella Jones, a community activist in NoHo who was leading the tour at that point, might have talked about Jacobs and Moses. If she did, I didn’t hear her. But Broadway is bustling at that point, and much of what she said was lost in the noise of the crowd.

Another guide, naturalist and educator Gabriel Willow, identified a rarely seen Question Mark butterfly for the group. In Union Square, he pointed out birds winging away from the park with worms in their beaks, almost certainly headed for nests full of young ones, he said.

“To have this intimate knowledge that this man is offering is fabulous,” Miss said.

Of course, Jacobs was primarily interested in people, and birds appear in Great American Cities mostly as metaphors for city-dwellers — “early bird walkers” and transient, high-rent-paying “birds of passage.”

Willow, on the other hand, is primarily interested in wildlife. “People …” he said at one point. “I don’t know that much about them.”

In the end, whether these walks had any real connection to Jacobs’ specific ideas or battles seemed beside the point. “Jane Jacobs informs everyone who thinks about cities,” said Miss. And surely from her seat in the pantheon of urban planning deities, Jacobs would have smiled down on the spectacle of thousands of city-lovers getting out on a weekend to explore the streets.

As Tomi Gatling, one of the walk participants, put it, “It’s too bad she’s gone, but I’m sure she’s doing good work where she is, too.”