Manhattan, 2010.

During the run-up to Wednesday’s debate, I remember seeing kids in the background of live shots wearing shorts and thinking, “Huh. Looks pretty nice in Denver.” Friday morning, it snowed there. It snowed this week in Minnesota and North Dakota, too, in some places, more than a foot deep. The New York Times notes that such a snowfall is rare.

Well, then so much for global warming, right? Nope.

For one thing, it’s not snowing all that early for these places. For another, as we constantly note, isolated weather extremes are different from the long-term trend. And, third, some scientists are expecting a bad winter — thanks in part to global warming.

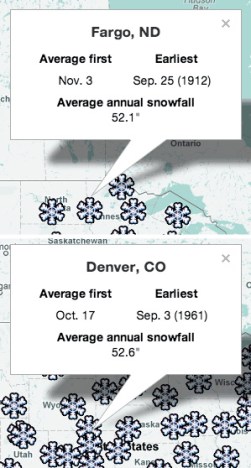

The Weather Channel has a nifty tool that shows the average date of the first snow for America’s major cities. In Fargo, N.D., the average first snowfall is on Nov. 3, a month away. But the earliest was on Sept. 25, 1912 — more than a week ago. Likewise Denver. It usually snows for the first time a couple of weeks from now, but it’s far from unusual that it should have snowed already.

That this year’s snowfalls are earlier than the average doesn’t mean anything anyway. Again, we point you to the “walking the dog” analogy. No matter how the weather is on any given day, the climate is doing the same thing: getting warmer.

Another way to look at it is with James Hansen’s analogy of loaded dice. We keep rolling the dice and expecting to get as many ones as sixes. But climate change is loading the dice, making sixes more and more common. Just because we rolled a one this time doesn’t mean we’ve got new dice.

The kicker: It’s possible that global warming actually will make this winter colder. Some scientists are suggesting that because of the unprecedented melt of Arctic ice, we could see a harsher winter in North America and Europe. Here’s the thinking:

Ralf Jaiser, a climate scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute … reasons that in autumn, the open Arctic Ocean sheds heat to the high-latitude atmosphere. The warming tends to reduce the large-scale atmospheric-pressure gradient and weakens the dominant westerly winds in the Northern Hemisphere. Those winds normally sweep warm, moist Atlantic air to western Europe; their weakening leaves the region more prone to persistent cold.

“The impacts will become more apparent in autumn, once the freeze-up is under way and we see how circulation patterns have influenced the geographical distribution of sea ice,” says Judith Curry, a climate researcher at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. But, she adds, “We can probably expect somewhere in the mid/high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere to have a snowy and cold winter.”

Mid- to high latitudes sounds about right for the snows in the northern Great Plains.

Anyway, now all of you who thought that a few inches of snow disproved climate change have finished this article and know that you’re wrong. The system works.