New records for green electricity sprout up every spring like daffodils.

Look at the recent run of cheerful headlines: Renewables generated more electricity than coal across the United States last month. On April 21, for instance, wind power contributed a record 65 percent of the electricity in the Southwest Power Pool, the organization which manages electricity across much of the Midwest. Britain just went seven days without generating any electricity from coal-fired plants for the first time since the Industrial Revolution. (That’s Britain! The birthplace of coal power.)

All this is good news for the climate. But the fact that these records always pop up in the spring is a symptom of a fundamental problem with wind, solar, and hydro energy: It’s controlled by nature. If we’re going to shift to a reliance on renewables, we’re going to have to find ways of evening out these seasonal swings.

Look at California. The state normally has to buy gobs of electricity from gas and coal plants from other states to keep the lights blazing in Los Angeles. But in the last two Aprils it turned into an exporter of electricity at certain hours when renewable energy was cranking. That had never happened before as far we know, said Anne Gonzales, public information officer for the California Independent System Operator, which manages electric flows through the state.

What’s special about the spring? That’s when people use the least electricity, and renewables produce the most. The weather is nice, so people leave their air conditioners and their heaters off. The days grow longer leading up to the summer solstice, the wind blows, and rivers surge.

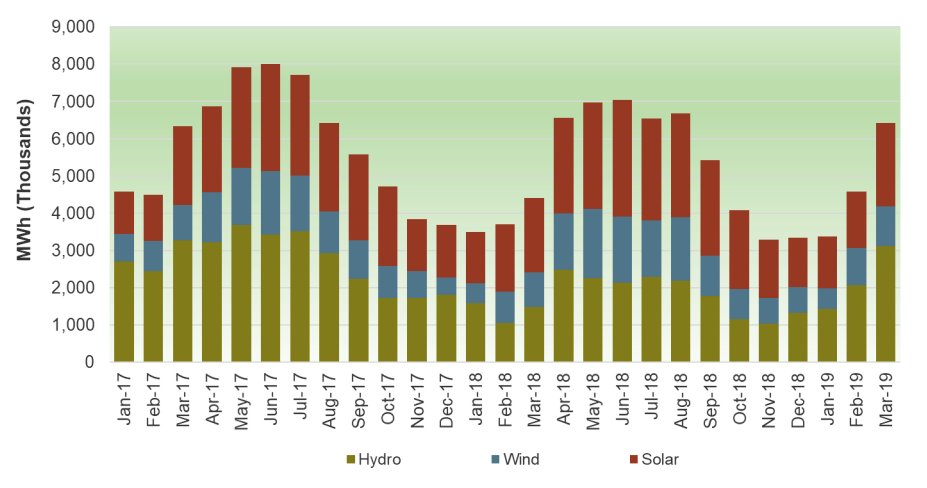

You can see the trend clearly in California, said Mark Dyson, an electricity expert at the Rocky Mountain Institute. “In the spring, especially in high water years like this one, there’s a lot of hydroelectric production without much ability to turn it down.”

Things would be a lot easier if graph was flat. California Independent System Operator

The surge of renewable electricity continues into the summer months, but people start turning on air conditioners by June, and the rise in electrical demand tugs fossil-fueled power plants back onto the grid.

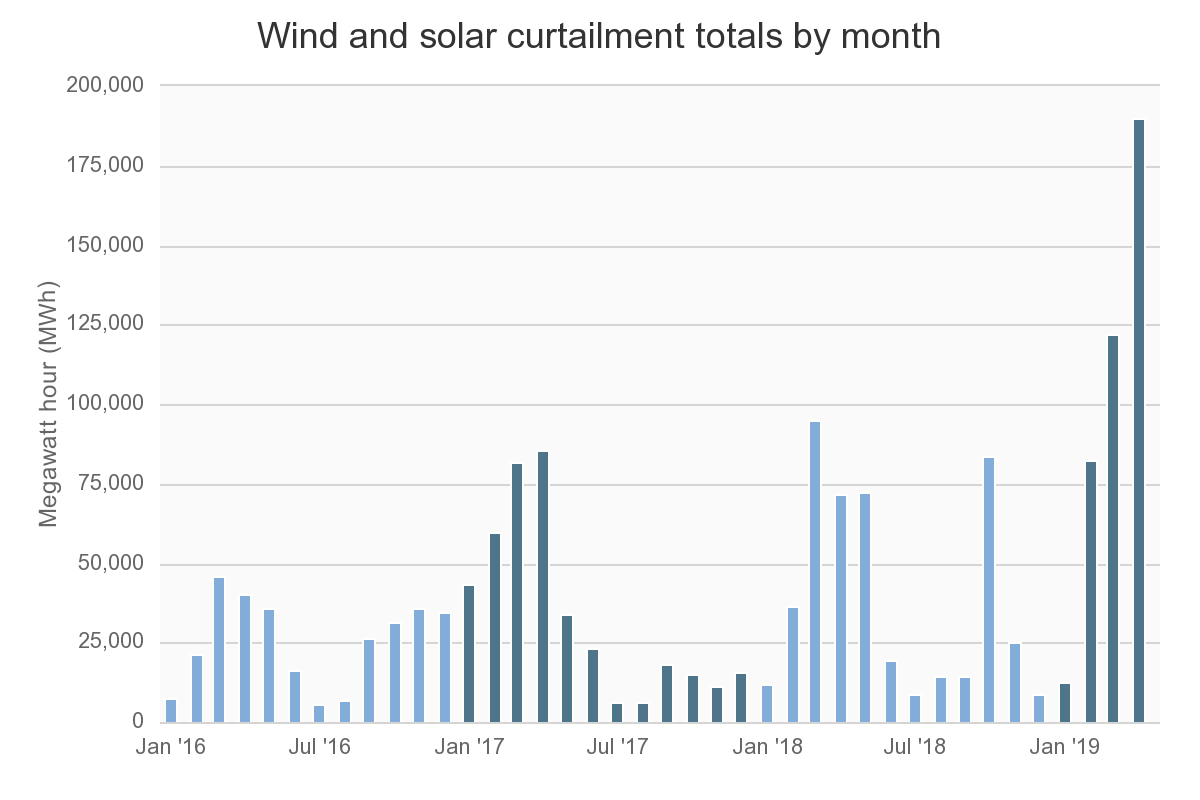

The fact that surges in renewable electricity production, and surges in electricity consumption occur at different times underscores the weakness of renewables. For instance, California also set a record this spring for the amount of renewable energy it couldn’t use. When there’s not enough room on the grid to make a connection between a solar farm and the phone you just plugged in, the power managers at the California Independent System Operator “curtail” that electricity — which usually means it just tells the solar farm to stop feeding electrons to the grid.

Another record. California Independent System Operator

In April, California set a new record by curtailing 190,000 megawatt hours, about as much as the entire country of Bhutan uses in a month. If we could have put April’s curtailed electricity to good use it would have been enough to prevent power plants from burning enough coal to fill 733 railcars. As people build more renewable energy sources, this trend will start cutting into their profitability.

Batteries and demand management (shifting the time refrigerators and water heaters turn on) can help smooth out little bumps, but they can’t handle these big seasonal swings yet. “You can build a utility-scale, four-hour battery pretty cost effectively today, but an eight-hour battery isn’t cost effective, and anything beyond that is just off the table,” Dyson said.

Venture capitalists have bet hundreds of millions of dollars inventing better batteries, he said, but for now, the two major solutions are building more transmission lines and expanding energy markets. Neither are simple.

It takes a lot of wrangling to find an unbroken strip of land where you can build a line of giant electrical pylons. A planned transmission line from Wyoming to the Hoover Dam got an important permit at the end of April allowing it to move forward after a decade of work, but another decade is likely to pass before electricity starts running through it. Experts have proposed even bigger transmission projects (a national grid!) that would surely take longer.

To expand electric markets, we don’t have to build anything or buy land. But, as California’s last governor, Jerry Brown, found when he tried and failed to merge with neighbors into a regional market, there are strong political interests that can prevent such markets from growing.

So far, these springtime records have been simple cause for celebration — rare indicators that a clean energy future might be possible. If we’re smart, they will also begin to serve as training sessions for managing electricity that surges with the seasons.