The coal industry is far more effective at preserving its political and economic power than it is at innovating cheap ways of getting coal out of the ground. In its push for continued relevance, the industry takes no prisoners in the mines or on Capitol Hill.

Consider the case of Reuben Shemwell, as told by Huffington Post:

Shemwell’s troubles started in September 2011. After his year and a half as a welder at mining properties in Western Kentucky, [Armstrong Coal] management fired the 32-year-old for what supervisors deemed “excessive cell phone use” on the job — an allegation Shemwell denied. Furthermore, Shemwell argued that the cell phone charge was merely a pretext for his firing. In subsequent court filings, he claimed the real reason he was canned was that he’d complained about safety problems at his worksite.

According to Shemwell’s filings with the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), the federal agency responsible for protecting miners, Shemwell had refused to work in confined spaces where he’d been overcome by fumes, and he’d complained to a superior that the respirators provided to welders were inadequate. Shortly before Shemwell was fired, he and a colleague also refused to work on an excavator while it was in operation, according to filings.

Not long after Shemwell filed his discrimination complaint, MSHA officials tried to inspect the site where he’d been working. According to court documents, Armstrong chose to shut the site down rather than subject it to MSHA oversight, which management said would be too costly. Ten workers were laid off.

The government decided not to hear a discrimination complaint Shemwell filed, which should have ended things — albeit unhappily for Shemwell. It didn’t.

Armstrong filed suit against Shemwell in Kentucky state court, claiming that the miner had filed a “false discrimination claim” against them, and that his claim amounted to “wrongful use of civil proceedings” — akin to a frivolous lawsuit.

Shemwell and his attorneys think that Armstrong Coal’s motive isn’t to repair its good name (assuming it once had a good name). Rather, the goal is to curtail complaints from employees and stifle whistleblowers. Efforts to silence employees drawing attention to safety concerns is hardly a new phenomenon; in 2011, whistleblowing miner Charles Scott Howard was fired by Cumberland River Coal, and then, after a court found the firing to be unjust, reinstated. What’s new in the Shemwell case is that Armstrong Coal took a further retaliatory step.

Despite wails during last year’s election that Obama was killing the coal industry, Big Coal appears to be feeling pretty confident. Politico reports on an emboldened industry:

The mining industry is optimistic about wielding Congress and the courts this year to push an agenda focused on expanding mining on federal lands and coal export capacity, as well as fighting EPA’s greenhouse gas regulations.

“There’s not one corner of the Congress where we don’t have strong friends,” said Rich Nolan, the National Mining Association’s senior vice president for government affairs. …

“We have a strong base both in committee and in the House floor,” Nolan said.

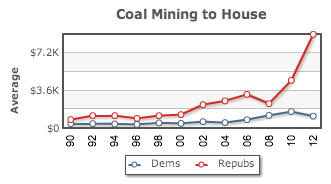

This is true. And as it happens, contributions from the coal mining industry to congressional candidates neared $5.5 million in the 2011-2012 cycle. The average contribution to House candidates spiked.

There’s not one corner of the Congress where the mining industry doesn’t have strong friends. Some of those friends even stop by for parties.

Yesterday, the National Mining Association gave a briefing to the media on its outlook for the year. In summary: It’s bright. The Charleston Gazette was there and quoted NMA President Hal Quinn: “The outlook for U.S. coal and minerals mining in 2013 is positive due to clear improvements in key sectors of the U.S. economy and the global demand for mined products, particularly in developing economies.” Quinn later reverted to 2012’s talking points, critiquing government measures that could slow production — things like EPA regulations on air pollution and increased government response to repeated mine violations. The future is bright — but it could be brighter.

It is certainly the case that the industry would like to expand. And it’s true that coal use continues nearly unabated internationally. But that doesn’t mean that the coal industry, particularly in Appalachia, is doing well. So the same scramble continues — punishing dissension among employees and currying favor in Washington.

If only the industry actually spent as much time and money and energy cleaning up its product. But, then, that wouldn’t make so much money.