On a blisteringly hot, sunny day this summer, Emory University researcher Arabella Lewis made her way through the underbrush in a patch of woods in Putnam County, Georgia, about an hour southeast of Atlanta. She was after something most people try desperately to avoid while in the woods: ticks.

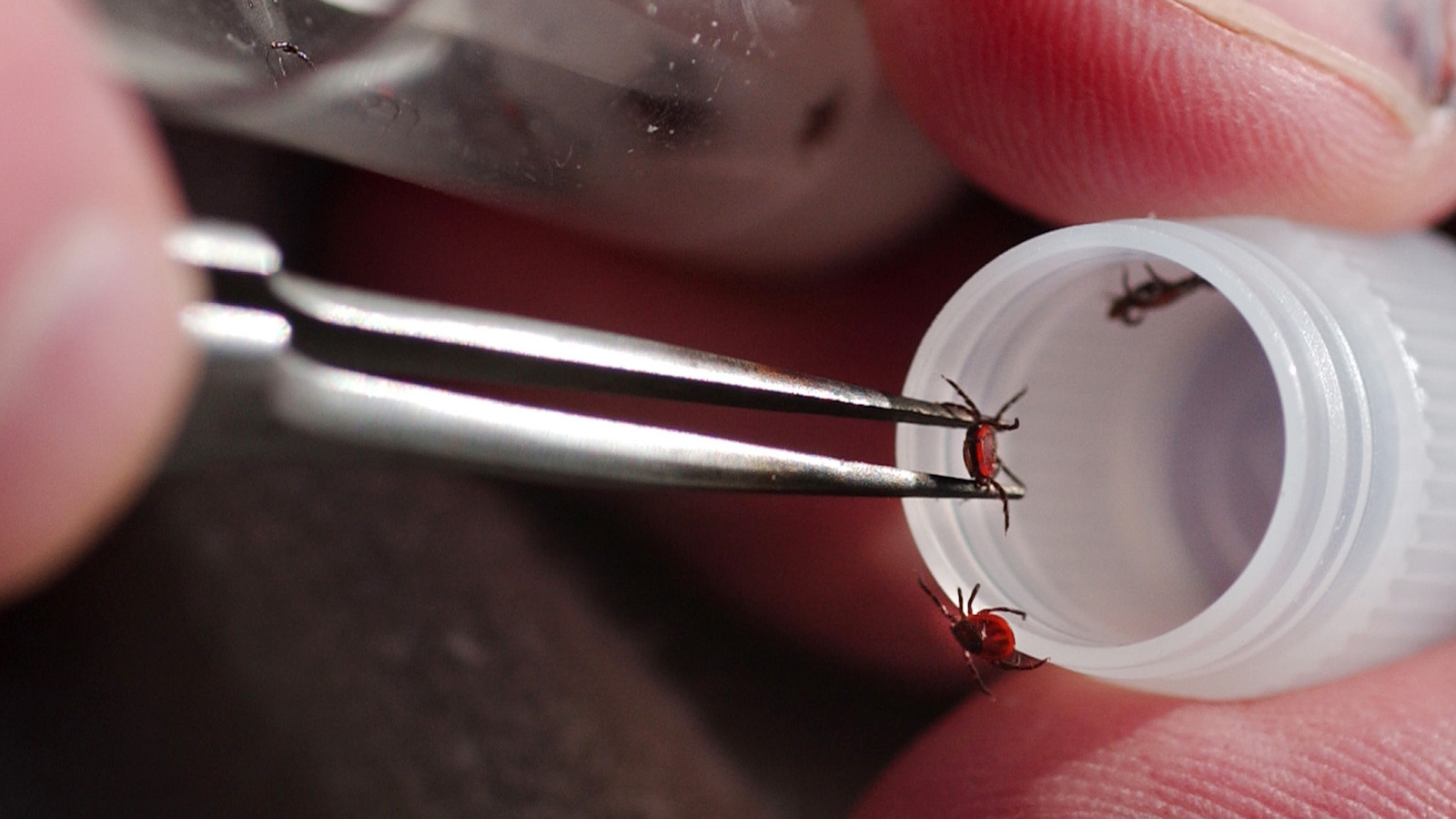

“Sometimes you gotta get back in the weeds to get the best ticks,” she explained, sweeping a large square of white flannel along the forest floor.

The idea was that the ticks could sense the movement of the fabric and smell the carbon dioxide Lewis breathed out and would grab onto the flannel flag.

“My favorite thing about them is their little grabby front arms, the way that they like wave them around, like they’re trying to grab onto things,” said Lewis, who’s been fascinated by ticks since she was a young kid growing up on a farm — and persistently dealing with ticks. “They have these little organs on their hands that smell, so they smell with their hands.”

Once a tick jumped aboard her flannel, Lewis picked it up with the tweezers she wore around her neck and deposited it into a labeled vial. Back at the Emory lab, she would test ticks for the Heartland virus.

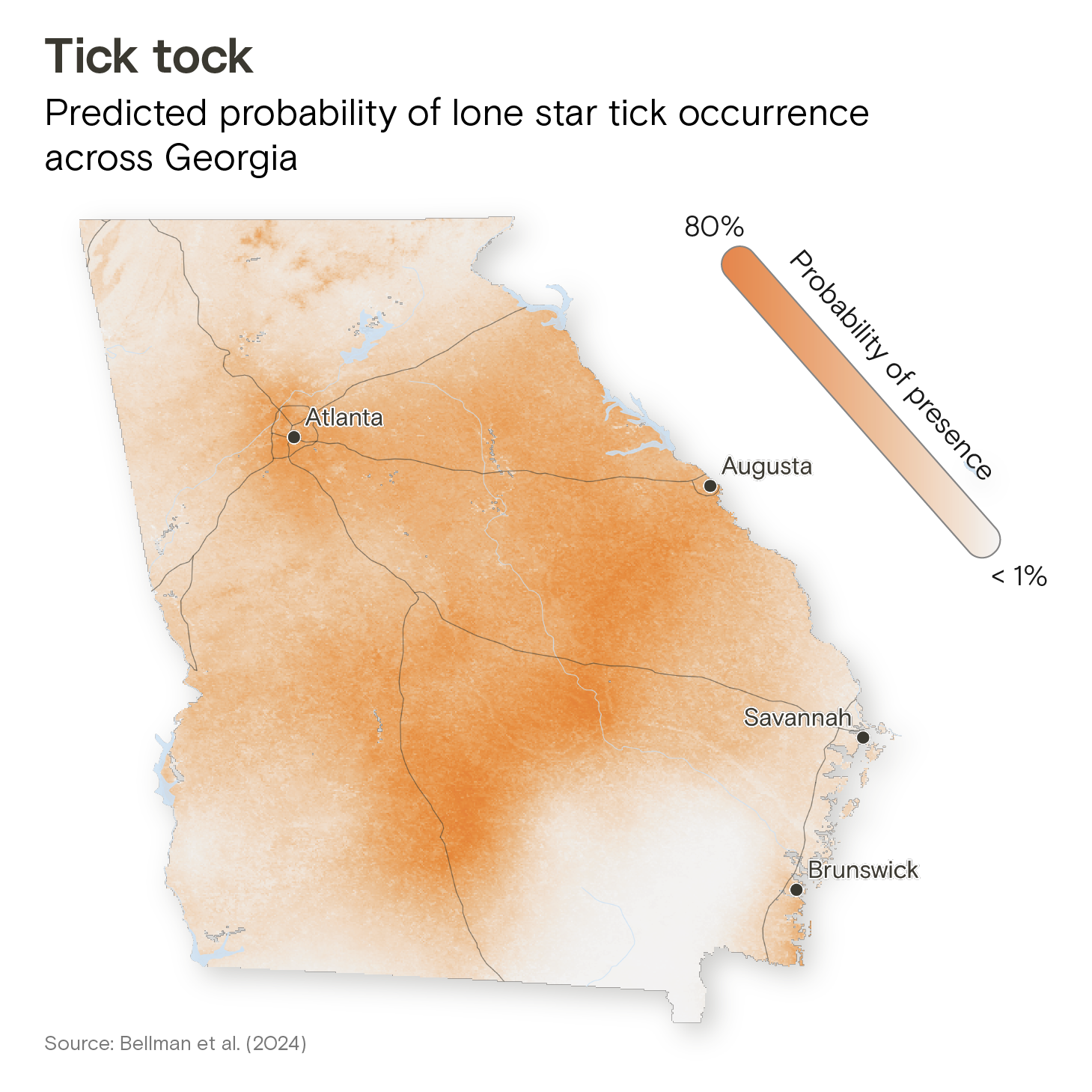

The tick collection and testing is part of an ongoing effort to get a better handle on Georgia’s tick population and the diseases the ticks carry. Earlier this year, Emory scientists published detailed, localized maps of where the state’s most common ticks are likely to show up. Now, they’re tracking emerging diseases like Heartland, a still-rare virus that causes symptoms like fever, fatigue, nausea, and diarrhea.

Nationwide, vector-borne diseases — that is, illnesses spread by carriers like ticks and mosquitoes — are on the rise, according to the CDC, and climate change is a major factor.

“Changes in climate lead to changes in the environment, which result in changes in ecology, incidence, and distribution of these diseases,” said Ben Beard, the deputy director of the CDC’s vector-borne disease division.

There’s a lot at play with vector-borne disease, not all of it climate change-related. These diseases live in animal hosts, so scientists have to consider how climate change is affecting those animals as well as the vector species like ticks. Humans keep encroaching on forested land full of both host animals and ticks, increasing their interactions and potential exposure.

As for the ticks themselves, longer summers and milder winters mean they’re coming out earlier and sticking around for longer. The lone star tick, which carries the Heartland virus and has long been widespread across the South and Mid-Atlantic, is expanding north and west as the climate warms. The black legged tick, which transmits Lyme disease, is also expanding its range — especially into areas that have seen significant warming, Beard said.

“So all of those things are kind of coming together,” he said. “And so the net effect is you have potentially more people over a broader geographic distribution, and over a longer period of time during the season potentially exposed to the bites of infected ticks.”

That’s exactly why the Georgia researchers are trying to get a better handle on ticks and their diseases: so they can help people avoid getting sick.

“My hope is that people in these regions that are predicted to have high probability will take more preventative measures when they’re out on hikes, or just out kind of in the yard, just generally interacting with our environment to hopefully prevent them from getting any tick borne diseases,” said Steph Bellman, who led Emory’s lone star tick mapping project.

As for the Heartland virus, it’s still largely a mystery, Lewis said.

“There’s no treatment at this point other than just kind of taking care of the symptoms,” she said. “It is considered an emerging pathogen, so pretty rare.”

More than 60 cases across 14 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as of 2022. That’s still a very small number, but scientists want to be ready in case it grows.

“We are taking the steps to understand it now so if an increasing human incidence were to happen, we know what can be done,” said Emory environmental sciences professor Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, who leads this research team.

They’re establishing a baseline of knowledge and research, he said, so they can stay on top of these diseases as they move and the climate changes.