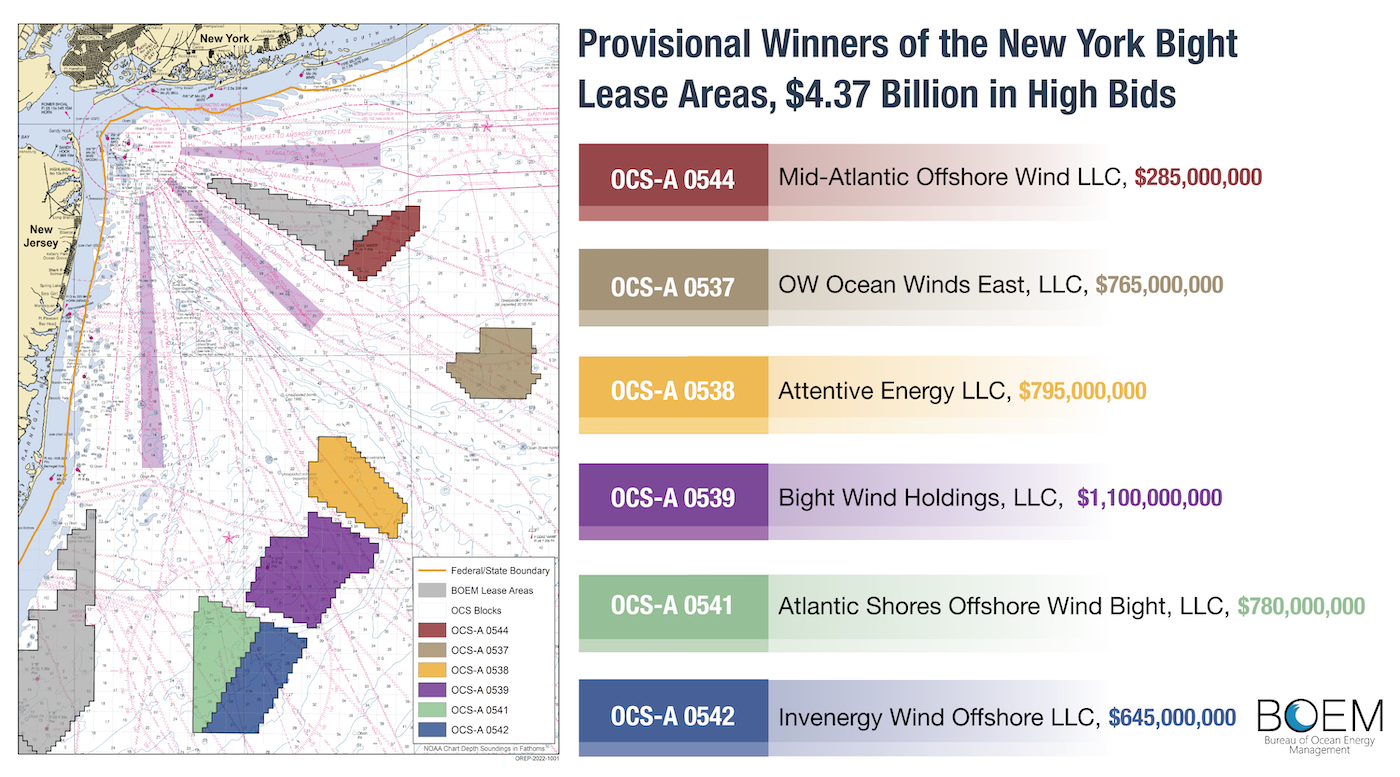

The Biden administration leased nearly half a million acres of the Atlantic Ocean for offshore wind development on Friday in the largest and most lucrative auction of its kind to date. Fourteen companies competed for the rights to develop wind farms on six areas of the New York Bight, a shallow stretch of sea that runs between Long Island and southern New Jersey.

The auction lasted for three days as bids rose higher and higher, closing out at a total of $4.37 billion on Friday afternoon. Bight Wind Holdings, a subsidiary of National Grid, won the rights to the largest tract for a whopping $1.1 billion, or $9,600 per acre. Other winning bids came from subsidiaries of oil and gas companies like Shell and Total, as well as international renewable energy companies like EDF Renewables. Only one U.S.-grown company, the wind energy powerhouse Invenergy, snagged a lease.

It’s a new era for wind development, with the per-acre lease price coming in at more than nine times the amount companies paid in the most recent U.S. offshore wind auction in 2018. Aaron Barr, a wind analyst at the energy consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie, told Grist the high bids were “a clear signal that offshore wind developers and investors are convinced of the sound business case for offshore wind in the United States.”

That’s mainly thanks to declining costs and increased state and federal policy support for the burgeoning industry. In 2020, Congress created a new 30 percent investment tax credit for offshore wind projects that begin construction before 2026. When President Joe Biden stepped into office last year, he set a national goal of having 30 gigawatts of offshore wind power — enough to power 10 million homes — installed by 2030. At the state level, New York has vowed to purchase 9 gigawatts of offshore wind power by 2030, and New Jersey has a goal of 7.5 gigawatts by the same date. Both states are also investing hundreds of millions of dollars in new ports to support offshore wind construction and maintenance, as well as manufacturing and supply chain infrastructure.

But while the case for investing upwards of $9,000 per acre in wind leases may be strong for investors and developers, the blockbuster sale might have a downside for residents in the region if it leads to higher electricity rates. Before wind companies move forward with their development plans, they will contract the power they expect to produce out to states for a set price. That price will ultimately be passed along to consumers.

Willett Kempton, associate director for the University of Delaware’s Center for Research in Wind, said higher electricity prices are possible, but the effect would likely be small — he estimates the unexpectedly high lease bids could result in power costing roughly 20 percent more than it otherwise would. But at the same time, he noted that the costs of development are still declining and that competition among wind companies to win contracts with states like New York and New Jersey could also exert downward pressure on electricity rates.

Fred Zalcman, director of the New York Offshore Wind Alliance, an industry advocacy group, thinks it’s too early to tell what the bids will mean for future consumer prices. He said that turbine efficiency is increasing and that there is also a growing domestic supply chain for offshore wind that will help bring down development costs. “So, yes, this is one input,” he said, “but there are many other factors and I think it’s premature to assume this will lead to higher prices.”

Zalcman added that the high lease prices don’t just reflect the strong business case for wind — they indicate a mismatch between demand for wind energy and the supply of lease areas. “I think if we develop more lease areas, that will help relieve some of the upward pressure on these lease prices,” he said.

Today, there are only two offshore wind farms in operation in the U.S. — the Block Island Wind Farm in Rhode Island and the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind pilot project — and they fulfill less than 1 percent of Biden’s 30-gigawatt vision. But the number of projects in the pipeline is substantial. The Department of Energy reports that offshore wind farms totaling more than 10 gigawatts are in the permitting stage, and lease areas that could support an additional 11 gigawatts have been sold. This week’s auction adds the potential for another 5.6 gigawatts of wind energy. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management estimates that wind farms on the six new lease areas could supply electricity to nearly 2 million homes.

Still, the timeline for Biden’s goal is tight. It takes years for a project to move from the leasing phase to construction, and then to operation. Chelsea Jean-Michel, a wind industry analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, told E&E News that the earliest she expects the new projects to come online is 2030.

Between now and then, the industry is set to be a huge driver of jobs and economic development in the Northeast. A Wood Mackenzie study from 2020 found that wind development in the New York Bight could support as many as 32,000 jobs a year while wind farms are being constructed between 2025 and 2030, and up to 5,800 jobs annually in the decades following. Many are likely to be union jobs — this week’s lease sale came with stipulations requiring developers to “make every reasonable effort to enter into a project labor agreement” for construction jobs. It also included financial incentives for developers to procure and assemble the major components of their wind farms domestically.

The six lease areas are located between 23 and 80 miles offshore and could eventually support hundreds of turbines. But East Coasters are unlikely to notice them too much — a visual impact analysis conducted for the South Fork Wind Farm off the coast of Long Island found that beginning at about 25 miles offshore, turbines tend to be visible from land only under ideal viewing conditions, and at about 40 miles they disappear from sight completely.