There was an interesting sentence buried in a Washington Post article that we referenced in a post earlier this week. The Post article assessed political support in Montana for an extension of the Keystone pipeline, noting:

In Montana, the majority of voters back it because TransCanada has included an “on-ramp” that will transport Bakken oil to the Gulf Coast. The oil is currently moved on rail cars, trucks and smaller pipelines.

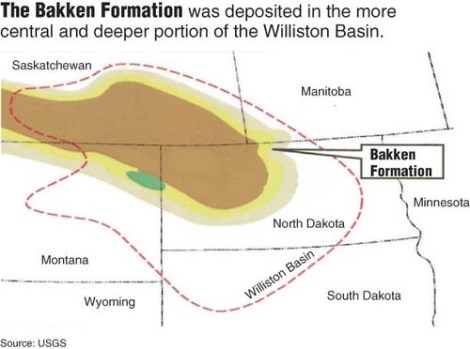

“Bakken oil” is oil from the massive Bakken formation.

Image courtesy of Oilshalegas.com.

The region stretches down from Canada over the borders of Montana and North Dakota. Estimates of its reserves have fluctuated over time. But most likely it contains over 100 mllion barrels of shale oil. The scale of the deposit has created a boom in both states over the past two years, with one estimate suggesting that there are over 6,000 wells now active.

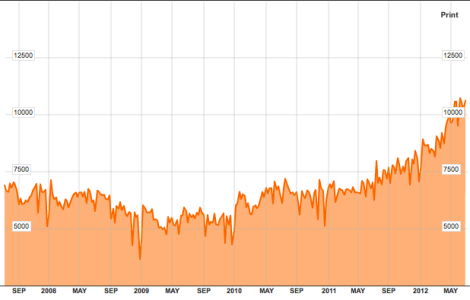

That’s a lot of oil to ship on rail cars. (Above, a seemingly endless train departs the Bakken region in July 2011.) The financial index that tracks how much oil is being shipped by rail, RAILPETR, has grown significantly over the past five years.

Growth in oil shipped by rail over five years.

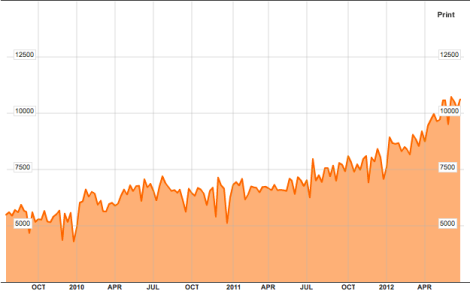

To make the increase more obvious, here’s three-year growth.

Growth in oil shipped by rail over three years.

The spike, it probably goes without saying, correlates to the expansion of drilling in the Bakken formation. Since it hit lows in 2009, the amount of oil shipped by rail has doubled — a secondary boom that has made rail companies nearly giddy:

Denis Smith is vice president of marketing for industrial products for Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway (BNSF). He says railroads have a long history of hauling crude petroleum, including from the Bakken, “but at this scale and at this volume, that’s what makes it unique and different and very exciting,” he says.

Smith says BNSF’s increase in traffic isn’t just from hauling crude petroleum from the oil wells in the Bakken and surrounding Williston Basin. He says these wells also need deliveries of drilling supplies like sand, pipe, and other heavy materials. He says the shortage of semi trucks and drivers and the current lack of pipeline capacity means companies are turning to railroads.

He says to accommodate the increase of drilling activity, BNSF has been laying new sections of track for its customers from its main line to the terminals to accommodate these shipments.

Burlington Northern was acquired by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in 2009, a move that has almost certainly paid off. There is also ancillary investment elsewhere in the country; those trains, after all, have to go somewhere.

Which raises another point. Yesterday, we noted that the safest pipeline is the one that doesn’t get built. But shipping by rail is not error-proof: Just this morning, a freight train derailed near Columbus, Ohio.

[protected-iframe id=”d857213361daa13b8cbd5ef798ec07c1-5104299-36375464″ info=”http://www.guardian.co.uk/video/embed” width=”460″ height=”370″]

So let us amend our argument from yesterday: The safest way to transport oil is to reduce the need to transport it at all. Warren Buffett will still manage to make ends meet.

Photo by Lord_Alex.