In the Pacific Northwest, where well over half the electric power comes from low-carbon hydro, the climate challenge is primarily about reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation. That is to say: it’s about cars.

Seattle’s Alaskan Way ViaductWSDOTDespite their ostentatious talk on climate, many of the region’s political leaders don’t seem to be making the transportation connection. Nowhere is that more evident than in the fight over how to replace Seattle’s crumbling Alaskan Way Viaduct, a two-mile-long elevated stretch of State Route 99 running along the city’s waterfront. It offers a gorgeous, iconic view of the city and the waterfront, but the next earthquake may well reduce it to rubble, so there’s pressure on to figure out what to replace it with.

Seattle’s Alaskan Way ViaductWSDOTDespite their ostentatious talk on climate, many of the region’s political leaders don’t seem to be making the transportation connection. Nowhere is that more evident than in the fight over how to replace Seattle’s crumbling Alaskan Way Viaduct, a two-mile-long elevated stretch of State Route 99 running along the city’s waterfront. It offers a gorgeous, iconic view of the city and the waterfront, but the next earthquake may well reduce it to rubble, so there’s pressure on to figure out what to replace it with.

The alternative with the most momentum, backed by Washington Gov. Christine Gregoire (D) and powerful business interests, is a gigantic bored tunnel — a concrete-heavy, emissions-intensive, multi-billion-dollar piece of old-school highway infrastructure devoted almost entirely to cars, shuttling suburban drivers past the urban core. What’s worse, it is being rammed through over the express opposition of Seattle voters.

Cary MoonIf such a megaproject sounds crazy to you in an era of climate crisis, peak oil, and starved state budgets, you are not alone. A coalition of urbanists and environmentalists is rallying around an alternative: a “surface street option” that would, as with San Francisco’s Embarcadero freeway, eliminate the highway, replacing it with a waterfront surface road, enhanced transit, and traffic improvements to surrounding streets and nearby Interstate 5.

Cary MoonIf such a megaproject sounds crazy to you in an era of climate crisis, peak oil, and starved state budgets, you are not alone. A coalition of urbanists and environmentalists is rallying around an alternative: a “surface street option” that would, as with San Francisco’s Embarcadero freeway, eliminate the highway, replacing it with a waterfront surface road, enhanced transit, and traffic improvements to surrounding streets and nearby Interstate 5.

One of the major forces behind the surface option is a rising star in Seattle progressive politics, Cary Moon, whose People’s Waterfront Coalition has done more than any other group to demonstrate that there is a viable alternative to car-centric madness.

I chatted with Moon last week about the history of the tunnel fight and what comes next.

——

DR: Can you lay out the basic story of how Seattle got here?

CM: [The Alaskan Way Viaduct] has been in bad shape for a while; the 2001 earthquake forced agencies into action. It got pretty severely damaged and they almost closed it down right then and there. But they decided, no, we’ve got to figure out how we want to replace it before we close it. So WSDOT [Washington State Department of Transportation] and SDOT [Seattle Department of Transportation] considered alternatives and came up with either a cut-and-cover tunnel or an elevated highway on the waterfront.

The mayor [Greg Nickels] liked the cut-and-cover tunnel, which was part elevated, part surface, and nine blocks of underground tunnel. The governor liked the elevated, because it was cheaper. They couldn’t agree, so they decided to toss it to the voters. In 2007, voters in Seattle looked at both options and said no (55 percent) to the elevated and no (70 percent) to the tunnel.

About two years prior to that, [the People’s Waterfront Coalition] had formed to say, wait a minute, why are we even assuming it has to be a highway? We did a lot of research on what was going on in other cities and brought all these case studies of giant urban highways that had been torn down – and the traffic impacts were better without the highway than with it. It’s counterintuitive, but it works. You’re giving people more choice. You’re distributing trips instead of channeling them all into one place, which can jam up when there’s congestion. It’s got environmental benefits, because you’re encouraging people to stay local rather than enabling sprawl and long-distance commutes.

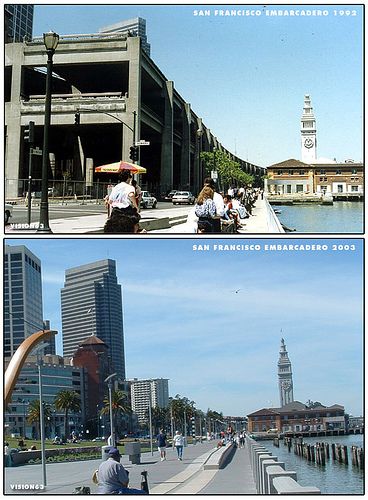

San Francisco’s Embarcadero, in 1992 and post-highway in 2003.vision63 via Flickr

San Francisco’s Embarcadero, in 1992 and post-highway in 2003.vision63 via Flickr

DR: What are some of the other cities who have been through this?

CM: The biggest is Seoul, Korea. They took out a highway that had 160,000 cars a day and replaced it with transit and a four-lane street. The Embarcadero in San Francisco: they didn’t think they could live without it, but they took it down and now that is one of the best places in San Francisco. Merchants love the local access rather than highway through-put. The West Side Highway in New York: there was a big fight about replacing it to avoid gridlock. The highway fell down and they realized, wait a minute, there’s no gridlock, maybe we don’t need it. They put in a surface street, maybe not the nicest street in the world, but it shows that a highway can be replaced by a better-connected street and life goes on. Portland took out a waterfront highway and reclaimed their waterfront for people.

DR: So, 2007 was when voters rejected both the tunnel and the elevated highway. Then?

CM: A lot of people at the time said that our side won, because [the surface-street option] was the only option left on the table. But it wasn’t that easy.

At that point, the city, county, and state said, OK, we failed the first round, let’s start again; let’s set up a stakeholder process where we’re going to stay in lockstep and come up with a solution together. After a year of study, the two winners were surface/transit/I-5 or a skinnier elevated highway with a lot of transit. A representative sample of the citizen groups involved signed a letter saying, yep, let’s do that, and keep the door open to a bored tunnel later if it ends up not providing enough car capacity. We thought we won again!

Christine GregoireBut then Gregoire checked in with the other people that she works with — Boeing, the regional Chamber of Commerce, other suburban interests — and they said, no way, that’s crazy, you have to rebuild that highway; you should just do the bored tunnel. The bored tunnel had been rejected by officials because it was too expensive and risky, but they talked Gregoire into it anyway.

Christine GregoireBut then Gregoire checked in with the other people that she works with — Boeing, the regional Chamber of Commerce, other suburban interests — and they said, no way, that’s crazy, you have to rebuild that highway; you should just do the bored tunnel. The bored tunnel had been rejected by officials because it was too expensive and risky, but they talked Gregoire into it anyway.

That’s where the situation’s been the past two years: the official preferred alternative is the bored tunnel and they’re pursuing it full-force.

DR: This is the juncture that confuses me. Seattle voters spoke. The city and state departments of transportation spoke. Civic groups spoke. Then the governor single-handedly overrode all that?

CM: Yes.

DR: Wow.

CM: I’m giving you my biased view. There were plenty of stakeholders in the 29 citizen groups who liked the bored tunnel from th

e beginning. But officials were saying, no, you don’t understand. That’s too expensive. We can’t do that. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.

The stakeholder process ended in December 2008. On Jan. 13, 2009, Gregoire announced with [former Seattle Mayor Greg] Nickels and [former King County Commissioner Ron] Sims that they’re doing the bored tunnel, along with $190 million worth of transit service (that’s how they got Sims to go along with it).

DR: What is the legal force behind the tunnel being decided? Is it official now?

CM: It’s still not official — it’s a “preferred alternative.” It’s just that politically it has a lot of momentum. Tunnel supporters want everyone to believe it’s past the point of no return. And as you can imagine, after nine years of arguing, people are exhausted and they just want to be done with it.

DR: Has nobody been able to mount serious protest?

CM: Until there was actually a budget, a plan on paper, it was hard to attack the tunnel. Tunnel proponents kept saying, don’t worry, the traffic’s just going to disappear! It’s totally affordable! There’s no risk! They spent almost two years in that mode, but the draft EIS [environmental impact statement] came out recently from WSDOT.

Now that the facts are on the table, politicians are forced to confront the reality, not the fantasy. A new citizens’ initiative [Move Seattle Smarter] is launching, saying the city can’t sign any agreements on the tunnel until there’s a full, transparent funding plan and someone steps up to the plate for potential cost overrun.

Seattle Mayor Mike McGinnWSDOTDR: That’s always been Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn’s ace in the hole against the tunnel, right? Cost overruns? [McGinn was elected in November 2009 on an anti-tunnel platform.]

Seattle Mayor Mike McGinnWSDOTDR: That’s always been Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn’s ace in the hole against the tunnel, right? Cost overruns? [McGinn was elected in November 2009 on an anti-tunnel platform.]

CM: Politically, that is what gets people the most irritated, that WSDOT picked this project and then said they’re only going to pay a certain amount and the citizens of Seattle will pick up the rest.

The state has agreed to pay $2.4 billion out of an estimated $3.1 billion. They’re hoping to get $300 million from the port, but that’s not secure yet. They’re going to toll the tunnel, so they’re going to float bonds for $400 million on future toll revenue. There’s $700 million of unsecured money.

Every single agency or government involved has said they are not paying a penny more for cost overruns. Kind of a problem. If the project goes over budget, there’s no money for that. Usually that would be fine, except in this case the cost estimate the state is using is their 60th-percentile number, meaning there’s a 40 percent chance it’s going to cost more.

DR: By the state’s reckoning. Is there reason to believe they might be under-counting?

CM: Given that nine out of 10 mega-projects exceed their budgets, tunnels are some of the worst, and this is the largest diameter [single-bore tunnel] ever attempted in the history of the world, yes.

–> PAGE TWO: WHAT THE SURFACE STREET OPTION WOULD LOOK LIKE

DR: Describe what the surface option would look like.

CM: The first thing is a regular four-lane street on the waterfront, which is what all the tunnel proponents say they’re really after.

A cross-section of what a waterfront surface street could look like. Exact design details are being worked out by James Corner Field Operations.People’s Waterfront Coalition

A cross-section of what a waterfront surface street could look like. Exact design details are being worked out by James Corner Field Operations.People’s Waterfront Coalition

Heavy transit investment in three main corridors: West Seattle to downtown, Ballard to downtown, and Aurora North to downtown. Probably bus rapid transit to start. We still need to figure out the exact details. McGinn is interested in light rail, but a lot of people think that takes too long and we need something fast and now. I would push for bus rapid transit now. As we create demand for transit, put in light rail on the routes that need it.

A (somewhat vague) rendering of the view of Seattle’s waterfront from Victor Steinbrueck park.People’s Waterfront Coalition

A (somewhat vague) rendering of the view of Seattle’s waterfront from Victor Steinbrueck park.People’s Waterfront Coalition

Improvements to I-5. Without increasing the footprint, you can rearrange the way the on- and off-ramps work and get a third northbound lane through downtown — just using the pavement we have more efficiently. All the through-trips trying to bypass the city can fit there. Similar tweaks to southbound can get 20 percent more throughput, which is plenty for the bypass trips.

Then a lot of small improvements throughout the street grid, to give transit better priority, to increase connectivity in neighborhoods, so that some of the streets that are parallel to the viaduct but aren’t very well-used could be better-used. In the South Lake Union neighborhood, for instance, all these wide streets are at about half capacity or less. If we could fix the intersections across Denny and Mercer, all those streets could be more useful.

Then, aggressive demand management, commute-trip reduction, carpooling. All those things are really cheap, and they add up. You can encourage about 25 percent of the trips not to happen through use of those programs.

DR: How much would the surface street option cost?

CM: It’s about a billion dollars less than the tunnel. That’s recently been affirmed by the director of SDOT. They’re all small projects.

DR: It also seems more resilient. If you have cost overruns, there are incremental ways of dialing back. There are no increments in a tunnel.

CM: Well said. Apples to apples, if you add up the city’s and state’s projects for the tunnel, it’s $4.2 billion. The surface/transit/I-5 solution would be $3.3 billion.

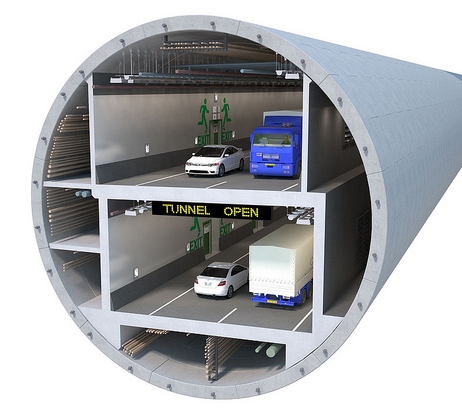

DR: Describe for us what the tunnel would look like, where it would be, and who would go through it.

The proposed tunnel.WSDOTCM: There would be two lanes each way {this info is in the next para}. The south portal, where it goes underground, is at Alaskan Way and King Street, right next to the Pioneer Square Historic District. Then it would stay along the waterfront

The proposed tunnel.WSDOTCM: There would be two lanes each way {this info is in the next para}. The south portal, where it goes underground, is at Alaskan Way and King Street, right next to the Pioneer Square Historic District. Then it would stay along the waterfront

for a bit, go under downtown diagonally, and come out at 6th Avenue and Roy, right by the Gates Foundation, and hook up with SR-99.

There would be no exits. No transit, because there aren’t any transit routes that bypass downtown. No bikes, obviously. The emergency egress is also quite interesting: If there is accident or fire and you need to get out, you have to walk to either end. There are no elevators or stairs. What if you’re on crutches, or in a wheelchair, or sick? You just have to wait until someone comes to rescue you. And the shoulders are tiny, just two feet and six feet, so it’s not like there is a lot of room for emergency vehicles if there’s congestion.

The tunnel boring machine used to dig Madrid’s M-30 tunnel.UrbanScraperDR: Are we talking about a single, gigantic drill that’s going to start drilling under Seattle?

The tunnel boring machine used to dig Madrid’s M-30 tunnel.UrbanScraperDR: Are we talking about a single, gigantic drill that’s going to start drilling under Seattle?

CM: Yes. It’s 55 or 56 feet across and something like 400 feet long. If it gets stuck, like if it bumps into a boulder, how would you ever get it out, repair it, or replace it? One of the tunnel experts hired by the city quoted a study that said one out of three boring machines like this gets stuck and has to be repaired, replaced, or removed. How would you do that under downtown Seattle?

DR: You’re tunneling under some pretty old and historic parts of Seattle, too, especially by Pioneer Square, right?

The propsed route for the tunnel.WSDOTCM: Yeah. They moved the alignment. They were going to do it right under 1st Avenue through Pioneer Square. They realized they couldn’t do that; there is just too much fragile stuff down there. So they moved it over to the waterfront, but it is still next to the Historic District, and then when it cuts diagonal, it goes underneath 14 historic buildings. Two of them are going to have to be removed, probably, because they can’t really repair them or protect them. Twelve are in harm’s way, but they feel like with jet grouting and monitoring and some money for repairs, they’ll be okay.

The propsed route for the tunnel.WSDOTCM: Yeah. They moved the alignment. They were going to do it right under 1st Avenue through Pioneer Square. They realized they couldn’t do that; there is just too much fragile stuff down there. So they moved it over to the waterfront, but it is still next to the Historic District, and then when it cuts diagonal, it goes underneath 14 historic buildings. Two of them are going to have to be removed, probably, because they can’t really repair them or protect them. Twelve are in harm’s way, but they feel like with jet grouting and monitoring and some money for repairs, they’ll be okay.

I haven’t told this to anybody in the media yet, because they don’t have it in writing, but I’ll just tell you: it goes under the historic Federal Building, and the federal government has never given rights to use land underneath their buildings. They just don’t do that. They’ve made that clear to WSDOT, but WSDOT is proceeding anyway. They’re moving forward as if that problem’s just going to go away.

DR: What’s going to happen now? If McGinn says Seattle isn’t going to sign onto an agreement until someone has committed to the cost overruns, what happens then?

CM: It’s not clear. Gregoire probably has enough authority to do this project without any cooperation from the city of Seattle.

DR: What? Seriously?

CM: If they decide that it is in the public good and local jurisdictions are not being helpful, they can take what they need and make it happen.

DR: Have they threatened to do that?

CM: I don’t know if they’ve said it in those words, but I think the city council recognizes that Seattle doesn’t have that much authority. That’s why they’re doing this play-nice, get-along routine rather than standing up for Seattle’s interests.

–> PAGE THREE: WHAT THE TUNNEL SAYS ABOUT CITY POLITICS

DR: Gregoire’s a Democratic politician. Isn’t Seattle part of her political base? Does she really want to flip it off?

CM: That’s an issue for her. But this debate’s now gotten polarized. The Downtown Seattle Association, the regional Chamber of Commerce, and the King County Labor Council are in heavy-duty cheerleading mode. The people who are opposing it are the good governance types, environmentalists, city types. I think Gregoire’s just made a political calculation that we’re not as important.

DR: Explain to me why downtown merchants want to build something that enables cars to bypass downtown.

CM: I have no idea.

DR: That seems against their interests, doesn’t it?

CM: I think their political calculation is that state highway department and certain legislators like those who run both transportation committees are hell-bent on some kind of highway. If they don’t do the bored tunnel, they’re going to force an elevated. And they don’t want the elevated because they want the benefit of a great civic waterfront, so they’re willing to put up with all the shortcomings of the tunnel, and all the risk, because it gets the waterfront they want.

DR: They don’t think the surface option is a serious option?

CM: Well, they signed the letter saying, let’s do the surface option and keep the door open for the bored tunnel. A pretty large group of downtown business leaders went on a field trip to San Francisco and learned about the Embarcadero and realized, OK, this can work. But they weren’t the majority and they probably felt a little bit too aggressive and progressive for their comrades, so they compromised on the bored tunnel. That’s the way I see it.

DR: I went to an event a few years ago and heard Gregoire talk about clean energy and climate change with great passion and eloquence. Yet there’s this disconnect when it comes to reducing vehicle miles traveled and building out transit. How does she square it?

CM: My guess is that she’s not an urban person. The argument that you can solve this problem with transit and demand management, and the city will be fine — she just doesn’t believe it. She’s been in Olympia her whole life. She doesn’t get why Amsterdam works, why Copenhagen works, and why New York City and San Francisco work. She just doesn’t think that way.

So when the Chamber of Commerce and Boeing say, you don’t understand, this is absolutely vital for us that we have more highways, she doesn’t have the tools to argue. In some ways that’s a failure of our side [to communicate that] good cities are about transit and walkability. It’s this mix of urbanism and environmentalism that we haven’t quite got right yet in Seattle.

DR: The Seattle City Council has proclaimed that Seattle is going to be carbon-neutral by 2030. Nickels started the Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement. We’re known all over the world as a green city, and we’re getting ready to build a highway mega-project.

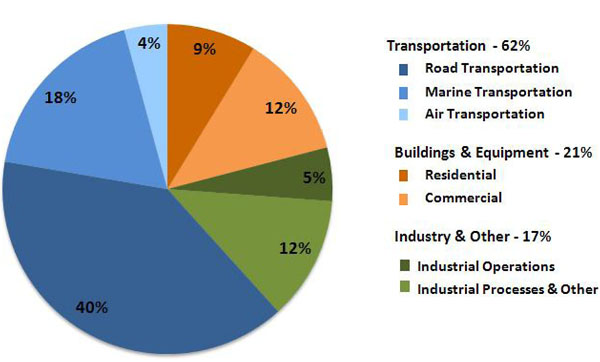

Sources of greenhouse gases in Seattle, 2008.Seattle Climate Protection Initiative: Progress Report 2009CM: We did an assessment a year or two ago of our progress on Kyoto goals and found we’re on track in all the areas but transportation. Until we confront that issue, we’re not going to make our goal. Everybody looked at that and just walked away from the commitment. We don’t even talk about the Kyoto Protocol anymore in the Mayors’ Climate Initiative. It faded from reality.

Sources of greenhouse gases in Seattle, 2008.Seattle Climate Protection Initiative: Progress Report 2009CM: We did an assessment a year or two ago of our progress on Kyoto goals and found we’re on track in all the areas but transportation. Until we confront that issue, we’re not going to make our goal. Everybody looked at that and just walked away from the commitment. We don’t even talk about the Kyoto Protocol anymore in the Mayors’ Climate Initiative. It faded from reality.

DR: In welcome political circumstances like these, why can’t smart urbanists and environmentalists win these fights? What’s going wrong?

CM: That’s such a hard question.

The debate too easily gets polarized into what’s good for business vs. what those wacko environmentalists want. Having a platform on job growth and economic growth and a green future together would help bring people together. We haven’t done that successfully yet, that’s one criticism I’ll take for our side.

Second, the status quo protection machine is incredibly powerful. With a city like ours that’s strong and wealthy, there are a lot of people who are happy with things the way they are. It’s hard to get them to aim for a different future, because change is scary and they’re not sure they’re going to make as much money in that future.

DR: I don’t get Boeing. They just want people to be able to get from Seattle to their factories in the suburbs north and south of the city?

CM: They freely admit they don’t even use the Viaduct.

DR: WTF?

CM: They just have this worldview that two highways is the magic number, not one highway and 10 good streets. Even though the data showed this is not true, they predicted that I-5 will turn to gridlock if the Viaduct is not replaced with another highway. The data proved that that wouldn’t happen, but that’s what they believe.[Climate activist] K.C. Golden and I met with the Boeing people. We had all the facts in front of us, and they just looked at us and said, no, we don’t believe that.

DR: How long will the tunnel take?

CM: Gov. Gregoire first said she’s going to tear down the viaduct in 2012, no matter what. Then she moved it to 2015. She recently moved it again to 2016. That’s when the tunnel would open.

With surface/transit/I-5, in 2008 they said it could be done by 2012. I guess that puts us at 2014 now.

One rendering of Seattle’s never-built monorail.DR: Seattleites voted for the Monorail twice, against the stadium, against the tunnel. We’re getting the opposite. Why is that?

One rendering of Seattle’s never-built monorail.DR: Seattleites voted for the Monorail twice, against the stadium, against the tunnel. We’re getting the opposite. Why is that?

CM: We’re a big enough city to have one power cabal downtown that basically does what they want. We’re not big enough to have two. If we were big enough to have two business groups fighting against each other, everything would be in the open, and maybe the public would get listened to.

DR: So what’s the next big event?

CM: On Dec. 16, [Seattle City Councilmember Tom] Rasmussen and [State Sen.] Ed Murray are going to be defending the tunnel plan. That should be interesting. Then the EIS comment [period]. A lot of organizations are looking at how bad this thing is for the city.

I think SDOT’s going to distance themselves more and more from the project [SDOT did just that yesterday], let WSDOT move forward on their own. That’s going to affect the politics of City Council.

Then, the governor thinks she’s going to sign a contract [with Tutor-Perini, which is currently facing fraud and racketeering charges] in January or February. That’s before the final EIS is even released. That’s kind of illegal, so there might be an EIS challenge.

DR: What’s the point of no return?

CM: I don’t know. There are some [state] legislators who are fed up with how expensive and risky it is. There is always a chance legislators could say, we’re done with this. That’s a long shot.

It’s funding silos. The state highway department only funds highways. They have one tool to solve every problem: build a highway. That’s not the right tool in cities most of the time.

DR: It’s tough to see how it’s the right tool in this case.

CM: If you were on the receiving end of that $2 billion, you might see otherwise.