Hello and welcome back to Record High. I’m Jake Bittle, and this week we’re going to explore the bureaucratic reason that the federal government doesn’t do more to help during heat disasters.

If you take a look at the primary law that dictates how the United States responds to disasters, the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1988, you’ll see a long list of perils that qualify for federal emergency aid. The act defines a “major disaster” as “any natural catastrophe (including any hurricane, tornado, storm, high water, winddriven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, or drought), or, regardless of cause, any fire, flood, or explosion.”

The word “heat,” however, does not appear on that list — or in any other part of the act, for that matter. That simple omission has had big implications for how we respond to heat waves.

In order to unlock the full resources of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, the president must declare a “major disaster” in a given area. But the Stafford Act doesn’t name heat as a qualifying catastrophe, and no president has ever made a disaster declaration over a heat wave. President Joe Biden has made more than 40 such declarations so far this year, but he hasn’t made one for the ongoing heat wave in the U.S. South. That’s despite the fact that the heat in Phoenix has become so severe that dozens of people have gotten burns from falling down on the sidewalk and local authorities have brought in freezer trucks to hold the bodies of heatstroke victims.

“Disaster funding is geared towards fixing expensive things that are broken, not people,” said Juanita Constible, a senior climate and health advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “So because heat is mostly a health consideration, it got left out.”

In theory, FEMA can reimburse state and local governments for any disaster response effort that exceeds local resources, but in practice it has never done so for a heat wave. Because the agency historically hasn’t devoted significant resources to fighting heat, Constible said, most state and local emergency management departments haven’t done much work to plan for heat either.

Part of the issue is that the damage caused by a heat wave is less physical than the devastation caused by a hurricane, tornado, flood, or similar event, so recovery isn’t just a matter of buying bricks to rebuild a school or sending trucks to carry away debris. Even so, heat waves place a massive financial strain on hospitals and power grids, and most local governments can’t afford to ramp up health services on short notice. Local economies also suffer as retail foot traffic plummets and outdoor industries like construction shut down.

During the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat wave, for instance, hospitals in Portland were dunking heatstroke victims in ice baths to keep them alive. But as temperatures climbed, eventually reaching 120 degrees Fahrenheit, they ran out of ice and had to scour the city for more. The Pacific Northwest heat wave ended up killing at least 229 people in Oregon and Washington over the course of the week, and perhaps as many as 600. Constible says the immense resources of the federal government might have been able to prevent some of those deaths if they had been available.

“When there are mass casualty events, there’s no big pulse of money that can come into the state or counties to help deal with the aftermath,” she told Grist. “One of the things that hospitals realized after the 2021 event, in Oregon in particular, was that they were wildly unprepared for the impact of that heat wave, and they had to do all this work after the fact to get up to some minimum level. Funds just aren’t really available for that kind of work without a disaster declaration.”

“Disaster funding is geared towards fixing expensive things that are broken, not people.”

Juanita Constible, Natural Resources Defense Council

The main FEMA initiative that could theoretically help with heat right now is the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities grant program, or BRIC, which distributes money to cities and states to help them prepare before disasters happen. FEMA released guidance this year signaling to state and local governments that they could use BRIC money to adapt to heat risks, and an agency spokesperson told Grist that more money will soon be available. But even this program hasn’t been much help so far: When the New York City Housing Authority submitted a BRIC application for a cooling center in 2020, FEMA declined to select the project for funding, saying it wasn’t cost-effective.

Representative Ruben Gallego, an Arizona Democrat, introduced a bill earlier this summer that would add “extreme heat” to the list of disasters in the Stafford Act. The bill has some bipartisan support, but Constible says it still faces long odds of advancing given the gridlock in the present divided Congress. In the meantime, Biden has asked federal agencies like the Department of Labor and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to get better at protecting workers from heat and measuring heat waves. But in reality, these measures can’t compare to the immense resources of FEMA’s standard disaster response.

At a press conference on Thursday where Biden announced the new measures, Phoenix mayor Kate Gallego said that local governments are doing everything they can to address heat risk, including by tapping pandemic stimulus money and using Inflation Reduction Act grants to plant new trees. But she also warned that the adaptation effort wouldn’t succeed without more help from the feds.

“We would love it if Congress would give you the ability to declare heat a disaster,” she said to Biden. “We need a whole-of-government approach.”

Reporting on extreme heat doesn’t just involve covering brutal temperatures. We need to focus on the solutions that can help us adapt and chart a new path forward. That’s why we’re continuing our extreme heat coverage through the end of September. But we need your help by MIDNIGHT TONIGHT to unlock critical funding. We are just $195 away from unlocking a $20,000 match to support our work. Please take a moment to donate what you can as every dollar counts.

By the numbers

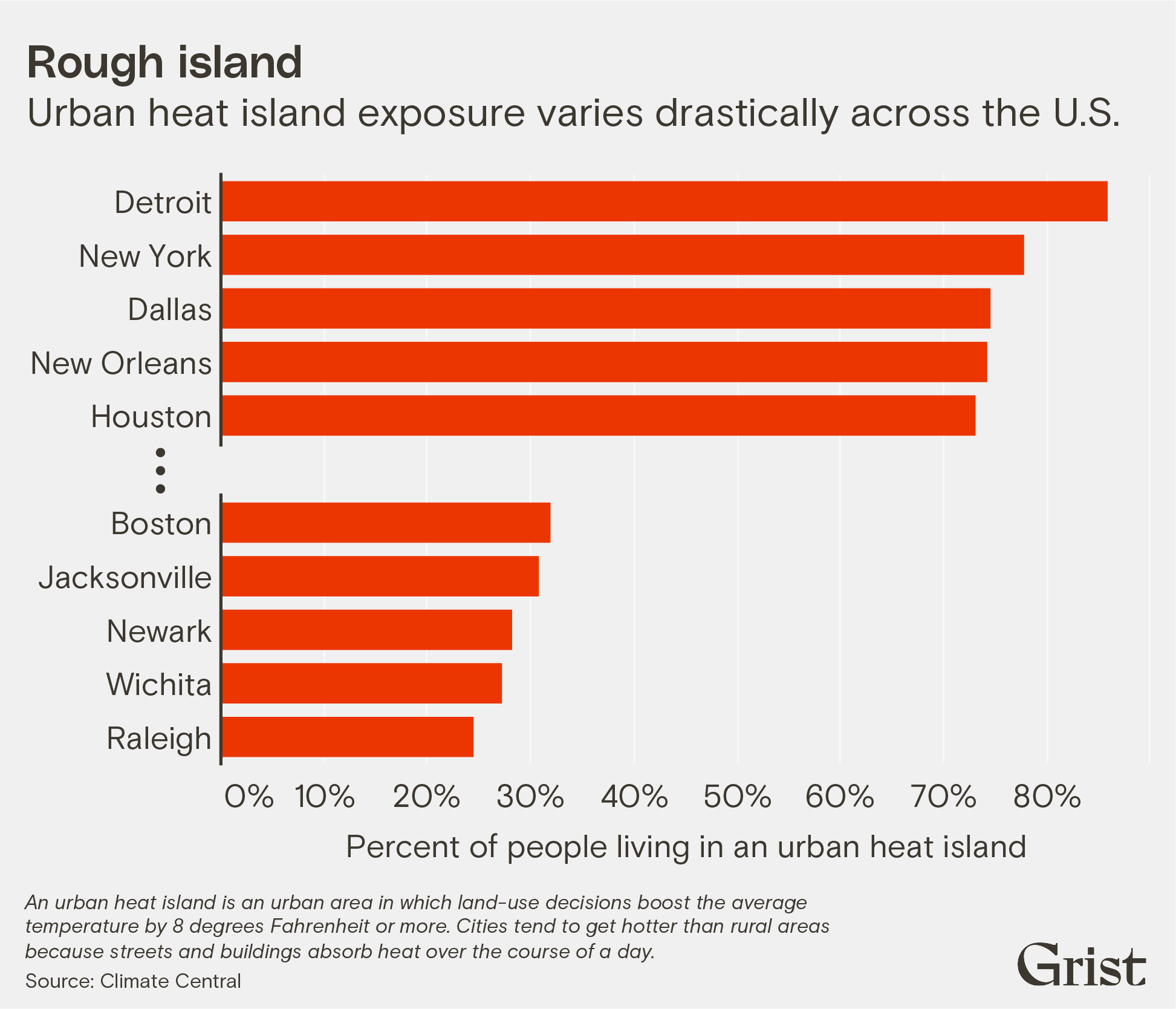

A new report from Climate Central revealed which U.S. cities suffer most from the “urban heat island” effect. Urban environments tend to get hotter than surrounding rural areas because streets and buildings absorb heat over the course of a day and release it at night.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern / Grist

What we’re reading

The hottest month ever: July was the hottest month in more than 120,000 years of recorded history. The last time the world was this hot, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were still vying for species dominance. My colleague Lyric Aquino reports on a month of devastating temperatures.

The Last of Us was a documentary: In the latest installment of a Grist-Associated Press collaboration on climate change and disease, the AP’s Camille Fassett explores how warmer temperatures are enabling a fungus known as Candida auris to spread through the U.S. like never before. The fungus can cause sepsis and fever when it infects human beings.

Grid stress in New York City: Amid a sweltering heat wave last week, New York utility ConEd asked customers to reduce their energy consumption during peak hours. The City’s Samantha Maldonado explains why this happened and why a popular call on social media to “turn off Times Square” wouldn’t have helped prevent blackouts.

What “record-breaking” really means: Every heat wave brings with it the news that dozens of temperature records around the world have been shattered, but Umair Irfan over at Vox explains that not all temperature records are created equal. The significance of a broken record in a given location depends on how long we’ve been measuring data there, and those nuances often get lost in flashy headlines.

More heat means more fossil fuels: One big winner from the past month of heat waves? Natural gas. Grid operators around the country have responded to skyrocketing energy demand from air conditioners and fans by burning more gas than ever. Despite rapid growth in renewable energy, gas is still the baseload fuel of choice in almost every region of the U.S. Timothy Puko of the Washington Post reports on the vicious cycle.