Hello everyone, and welcome back to State of Emergency. I’m Jake Bittle, and today we’re going to be talking about the lasting political impact of one of the worst natural disasters in American history.

When we talk about the impacts of climate change in the United States, and in particular the racial dimension of those impacts, there is no escaping Hurricane Katrina. The 2005 storm that burst the levees in New Orleans remains the costliest hurricane ever to hit the U.S., as well as perhaps the worst humanitarian crisis of the past century to take place on American soil.

In the almost 20 years since Katrina, academics and demographers have conducted reams upon reams of research about the political and social impacts of the storm, both on New Orleans itself and on the tens of thousands of New Orleanians who never moved back. Studies have explored how the storm impacted trust in the government, how it affected turnout rates in later mayoral elections, and whom storm victims were most likely to blame for the botched emergency response, to name just a few.

But Katrina also had a profound impact on the cities where evacuees fled. In Houston, 300 miles to the west, more than 200,000 victims arrived after the storm, many coming in on evacuation buses and camping out on the floor of the Astrodome. Knowing that it would take months or years for New Orleans to rebuild, the government of Houston undertook a massive resettlement effort to find those evacuees long-term housing in Texas rather than put them up in trailers or hotel rooms. Many of them later chose to settle down in Houston for good.

This resettlement effort earned Houston mayor Bill White national praise, but it also caused significant local backlash. Longtime residents of Houston soon started to complain that evacuees had imported old gang conflicts from New Orleans, causing the city’s murder rate to spike in 2005 and 2006. There was little data to support this fear, but a moral panic exploded in the city regardless, with dozens of newspaper articles stoking concerns about evacuee crime. The White administration, facing a looming reelection campaign, responded by beefing up enforcement of low-level traffic and drug offenses, arresting some evacuees, and pushing others back to New Orleans. This fear of a crime wave had an obvious racial dimension — New Orleans had a much larger Black population than Houston at the time — and it created a prejudice against New Orleanians who were seeking jobs or trying to acclimate to local schools.

The anti-evacuee sentiment mellowed out in later years, but the political backlash to the Katrina resettlement holds lessons for the future of climate displacement. As climate disasters worsen, forcing thousands of people from their homes every year, they create huge political upheavals for the communities that receive those displaced people. Even in a city as large as Houston, which had the room and resources to accommodate an influx of evacuees, the Katrina diaspora created a social panic. For other communities — like Duluth, Minnesota, which some have speculated could be a “climate haven,” or Boise, Idaho, which has absorbed many victims of the 2018 Camp Fire that destroyed Paradise, California — the backlash could be even more significant.

In order to navigate future climate disruptions, politicians will have to be prepared to deal with concerns about housing, jobs, and crime — concerns that may cross over into outright racism or xenophobia. It’s one more way in which climate disasters have scrambled political attitudes and altered the beliefs that bring people to the ballot box.

You can read more about how Katrina changed Houston’s politics in our full story here.

P.S. Have you just joined us in this newsletter? Back issues of State of Emergency are available here, and you can also read all the reporting in this series.

A barrage of disasters

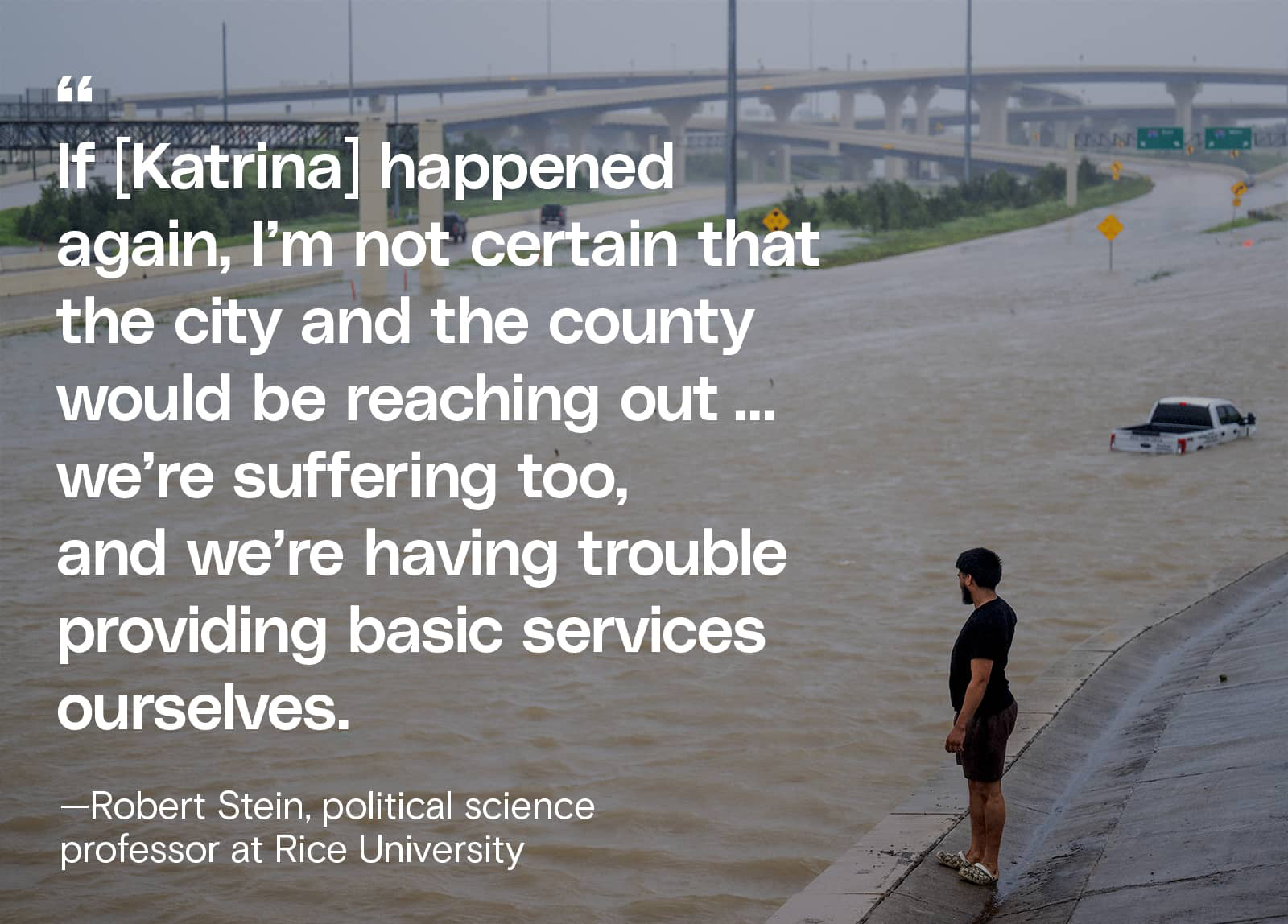

The city of Houston and surrounding Harris County helped resettle thousands of evacuees from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, but since then Houston has seen a string of costly disasters, from Hurricane Harvey’s epic rainfall to a deadly ice storm in 2021.

Above: A person looks out towards the flooded interstate after Hurricane Beryl swept through the area on July 8, 2024 in Houston, Texas. Brandon Bell / Getty Images

What we’re reading

Climate change supercharged wildfires: New research has found that many of last year’s worst wildfires — including blazes in Canada, Greece, and the Amazon rainforest — were made more dangerous by climate change. My Grist colleague Sachi Mulkey has a story breaking down the disturbing new data. Read more

Read more

Will Hawaiʻi tighten building codes?: After the Lahaina fires, Hawaiʻi has an opportunity to prevent future blazes by imposing stricter building codes — but these efforts can become “political dynamite” if they make rebuilding more expensive or force other homeowners to make costly upgrades, reports Civil Beat. Read more

Read more

Storm damage on Long Island: Governor Kathy Hochul of New York declared a disaster emergency in Suffolk County on Long Island after a recent storm, and she also offered $50,000 rebuilding grants for homeowners who suffered damage from the event. The Long Island suburbs are home to one of the nation’s swingiest congressional seats. Read more

Read more

Frost turns up the heat: Maxwell Frost, a Florida congressman and the youngest member of the House of Representatives, spoke about climate impacts in his state at the Democratic National Convention, citing hurricane-induced flooding and heat waves that endanger agricultural workers. Read more

Read more

Ernesto knocks out Puerto Rico’s power: Tropical Storm Ernesto sliced past Puerto Rico more than a week ago, but thousands of residents still haven’t seen their electricity come back on, in another demonstration of how fragile the island’s power grid has become. Read more

Read more