When it comes to children in California and lead exposure, James R. Williams doesn’t back down. As the Santa Clara County Counsel, he held steady for nearly 20 years in a legal battle that held former lead paint manufacturers accountable for promoting lead paint for use in homes despite its known toxicity. These days, he’s gearing up for another fight — and this time it’s with the federal government.

Santa Clara County is a diverse, majority-minority county of nearly 2 million people in the heart of California’s wealthy Silicon Valley. As of January 1, it’s also possibly the first county in the nation to ban the sale of toxic leaded aviation fuel at its two general aviation airports. The Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors passed the ban last August as an immediate stop-gap to reduce the airborne lead emissions that pollute the neighborhoods surrounding the Reid-Hillview Airport. That airport is among the airfields listed by the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, as most likely to exceed federal air quality standards for lead because of leaded aviation gasoline emissions.

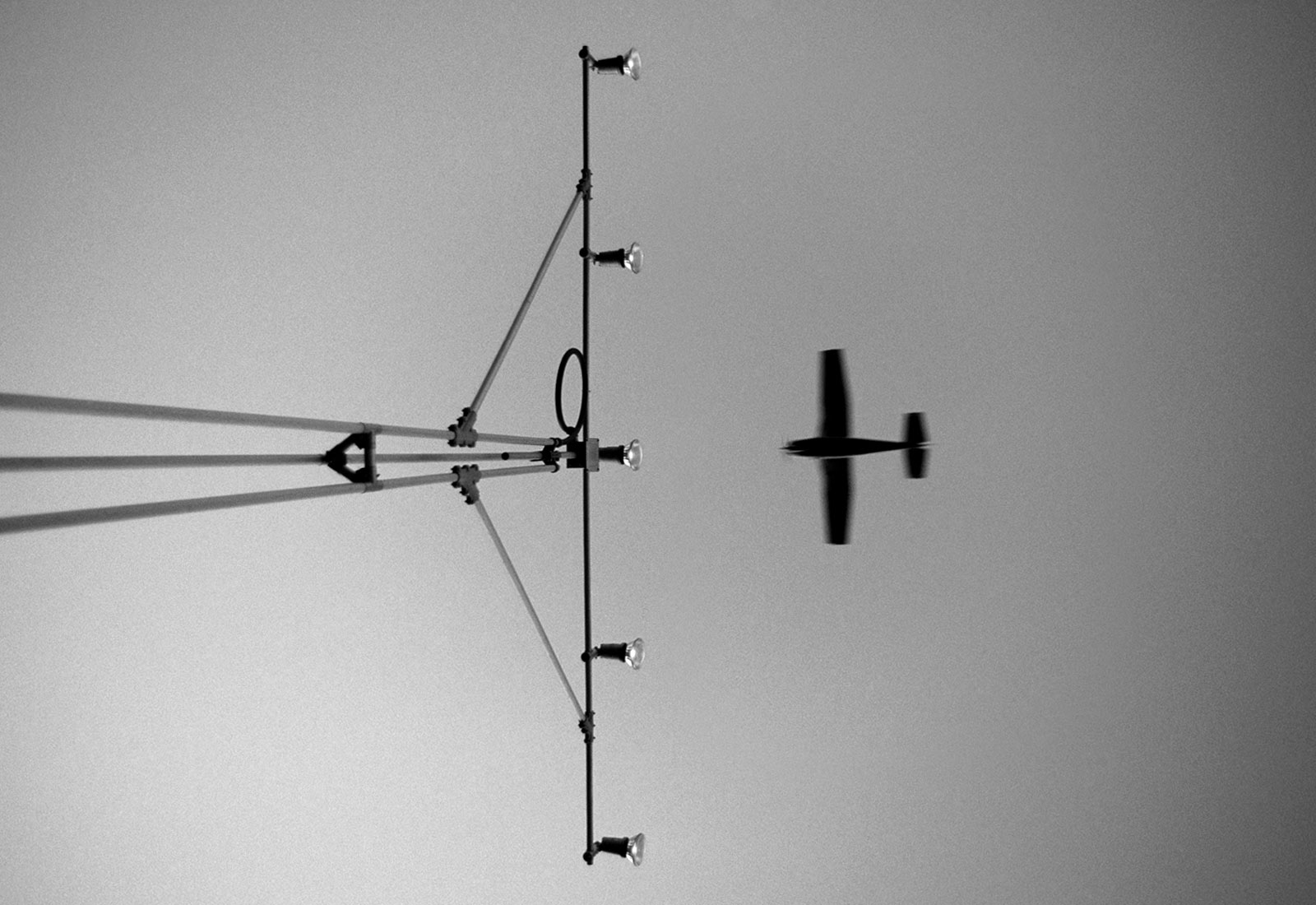

A study commissioned by the county found that children in the predominantly Latino neighborhoods around Reid-Hillview Airport in East San Jose are being poisoned by lead. Children within half a mile of the airport experience substantially higher increases in blood lead levels during high traffic periods of piston-engine airplanes, which are small gasoline-powered aircraft — levels that surpass the increases experienced by children of Flint, Michigan, during the height of that city’s lead water crisis, the researchers found.

“The ensemble of evidence compiled in this study supports the ‘compelling’ need to limit aviation lead emissions to safeguard the welfare and life chances of at-risk children around Reid-Hillview,” the study found. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has concluded that lead is not safe at any level in children’s bodies.

Williams’ office was part of a national coalition last year that pressed the EPA to classify leaded aviation gasoline air pollution as a danger to public health and the environment — what’s known in government-speak as an “endangerment finding.” Environmental and community activists across the country want the U.S. to address the dangers of leaded aviation fuel used by piston-engine aircraft, which are the largest remaining source of lead air emissions in the country, and say that government inaction continues to put people in harm’s way.

In January, the EPA announced that by year’s end it plans to issue a proposed endangerment finding, which determines whether lead emissions from piston-engine aircraft cause or contribute to air pollution that endangers public health. The process will include a public review and comment period, and a final decision on the endangerment finding by 2023. An EPA-issued finding on this matter would then allow the federal government to propose regulatory standards to address the harm caused by the toxic additive in aviation fuel. But this could take years, a delay that Williams says the communities who live around East San Jose’s Reid-Hillview Airport can’t afford.

“We have a crisis today, right here, right now in this neighborhood,” Williams told Grist. The county-owned Reid-Hillview poses one of the highest lead exposure risks of any general aviation airport in the nation due to its high traffic and setting in a densely populated urban center, he noted.

“We have been pushing for the EPA action,” Williams said. “We welcome it. We’re excited about it. We need nationwide action — that doesn’t address the harms that are happening to 13,000 children adjacent to Reid-Hillview airport right now.”

In December, the Federal Aviation Administration, or FAA, issued a notice informing Santa Clara County that it had launched an informal investigation into the ban, and called on the county to suspend the date the ban would go into effect. The county has remained firm on its decision to keep the ban in place, said Williams. In a response to the FAA, the county states that it has not banned the use of leaded fuel at the county airports, and that its actions — authorizing the use of county-owned fuel tanks exclusively for unleaded fuel and prohibiting the storage, sale, and distribution of leaded fuel — is consistent with the law.

After airport tenants, pilots, and aircraft owners filed complaints with the FAA claiming the prohibition is unreasonable, and would force higher performance planes to refuel elsewhere, the federal agency opened its investigation. Some pilots described the ban as “unjustly discriminatory” because some aircraft can only use 100LL fuel, which contains tetraethyl lead that is added so that high performance aircraft can safely operate. “We are deeply concerned about rushed timing and an increased risk of misfuelling in an airport network with fragmenting fuel supply,” stated one letter submitted to the FAA by a coalition of groups including the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association.

The FAA notice claims that the county moved forward with its plans without input, advance notice, or prior approval of the FAA, and that until the federal government certifies the use of unleaded fuel in all aircraft, the county is not allowed to ban or phase out leaded fuel or take any actions on fuel that conflict or undermine federal law and airport access. An FAA spokesperson declined to comment on the matter because of the investigation. In its December notice to the county, the FAA noted that the federal agency is “committed to building a sustainable aviation system and a lead-free future.”

Aviation gasoline, or avgas, is used in the roughly 170,000 piston-engine aircraft estimated to be in use nationwide, including airplanes and helicopters, which operate out of more than 13,000 airports. Nearly all of these aircraft burn a grade of avgas that contains lead. These small, gasoline-powered general aviation aircraft generated 468 tons of lead emissions in 2017, according to EPA data. More than 5 million people, including 363,000 children under age 5, live within 500 meters of these airport runways, and more than 160,000 children attend school in these areas, a 2020 EPA analysis found.

“There are thousands of these airports across the country, but the biggest, most emitting airports are disproportionately in low-income communities and environmental justice communities,” said Jonathan Smith, a senior attorney with the nonprofit Earthjustice, which in the petition to the EPA represented Friends of the Earth and a coalition of environmental advocacy groups across the country who have pressed the agency to remove lead from aviation fuel for nearly two decades.

The scientific consensus is that no lead level is safe for children. Experts have found that the neurotoxin has irreversible effects on a child’s developing brain, leading to a cascade of harms — such as cognitive deficits, behavioral issues, and educational delays — and making immediate action imperative. Given decades of scientific evidence demonstrating the harms of lead exposure, particularly for children, environmental advocates cheered the EPA’s decision, but said it was long overdue and doesn’t resolve the immediate threat faced by children who live next to general aviation airports.

Moving forward, the fight for lead-free aviation fuel will have to take place on both the local and national front, said Marcie Keever, program director for Friends of the Earth, which petitioned the EPA in 2006 to make an endangerment finding and subsequently filed a lawsuit in 2012 over the agency’s “unreasonable delay” in responding to the petition. “When you’re talking about cities and counties and they’re saying: We want to go unleaded in our communities and we support that at the national level — that’s even more powerful,” Keever of Santa Clara County’s ban.

Friends of the Earth hopes that the FAA makes a more aggressive push to implement more immediate solutions, including those suggested by the the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, which concluded in a 2021 report that while there’s no single solution to eliminate leaded aviation fuel, multi-pronged concerted efforts are needed to reduce its use.

One example the report offered was to invest in additional fuel storage at airports that would offer a very low-lead aviation fuel, which currently is not in production — but this option could reduce lead emissions by 20 percent. Another possible solution would be to offer an unleaded lower-octane gas that could be used by half to two-thirds of the nation’s existing piston engine fleet. That option could reduce aviation lead emissions by 30 percent.

Instead of fighting the ban, Williams said a smarter approach for the FAA would be to embrace Santa Clara County’s efforts, encourage other airports around the country to do the same, and work with the EPA to swiftly remove lead from aviation fuel. “I think the bigger threat is the failure to address these harms to the communities around the airports,” said Williams, noting that the FAA’s stance on the ban will harm the very environmental justice communities the Biden administration has pledged to help.

Late last month, the White House touted the first anniversary since President Biden laid out the administration’s environmental justice agenda. Several actions related to lead exposure were mentioned, including the need to address the continued use of leaded aviation fuel. EPA Administrator Michael Regan also emphasized the importance of protecting children from lead when he announced the EPA’s proposed endangerment finding. “Protecting children’s health and reducing lead exposure are interlocking priorities at the core of EPA’s agenda,” he stated.

The FAA exerts extraordinary control over airports, said Williams, and should apply a lens that includes public health and welfare as part of its approach. “That would be aligned with the Biden administration’s goals,” said Williams, “and in my view, that would be aligned with the FAA’s charge to run a safe and healthy municipal airport system.”

Editor’s note: EarthJustice is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.