El Paso homeowners conserve water by using crushed rocks and native, low-water plants (such as cacti) for landscaping, a practice known as xeriscaping. El Paso also has a city ordinance to limit turf use to no more than 50 percent of a house’s landscaping space.Photo: Marie GilotEl Paso is the Wild West. Dust storms, scorching temperatures, and 9 meager inches of rain a year (New York gets 43).

El Paso homeowners conserve water by using crushed rocks and native, low-water plants (such as cacti) for landscaping, a practice known as xeriscaping. El Paso also has a city ordinance to limit turf use to no more than 50 percent of a house’s landscaping space.Photo: Marie GilotEl Paso is the Wild West. Dust storms, scorching temperatures, and 9 meager inches of rain a year (New York gets 43).

A border town at the very end of Texas and in the middle of the Chihuahuan desert, El Paso is a great setting for a cowboy movie, but the harsh landscape makes the future uncertain for this growing city of 600,000 people.

In 1979, a study warned El Pasoans that if they continued to dip freely into their underground aquifer, it could run out of fresh water by 2030. The town turned that bleak prognostication around when it made water conservation a priority 20 years ago, and became a national model in the process. (Read a Q&A with the head of El Paso Water Utilities.)

The beginning

Today, El Paso is a city that’s hyper conscious of water. The use of low-water plants and crushed rocks in landscaping — a practice known as xeriscaping — is the norm. Neighbors rat out neighbors if they see water runoff in the streets. And water news gets front-page treatment in the local press. But that wasn’t always the case.

Twenty years ago, El Pasoans were blissfully wasting water. Lavish lawns were everywhere and the Hueco Bolson, the aquifer that provided 90 percent of El Paso’s water, was being depleted by a foot and a half per year. Then, in 1991, the El Paso Water Utilities board put together a long-term plan. The highest priority was a conservation program which included a mix of strategies — some compulsory, some incentive-based, and some voluntary — including:

- A tiered water rate structure that punishes heavy users.

- A landscaping ordinance limiting lawns to no more than 50 percent of landscaping space.

- A watering ordinance that bans residential watering on Monday, and between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. during the summer. The ordinance allows even-numbered addresses to water on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, odd-numbered addresses on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Sundays. No water is ever allowed to flow into the street.

- A series of rebates which include $1 back for every square foot of turf replaced; $100 to switch to a front-loading washing machine; free low-flow shower heads; and rebates for low-flow toilets and to change from swamp coolers to refrigerated air units.

- Education programs including school visits by “Willie the water drop,” and recent construction of the Tech2O education center.

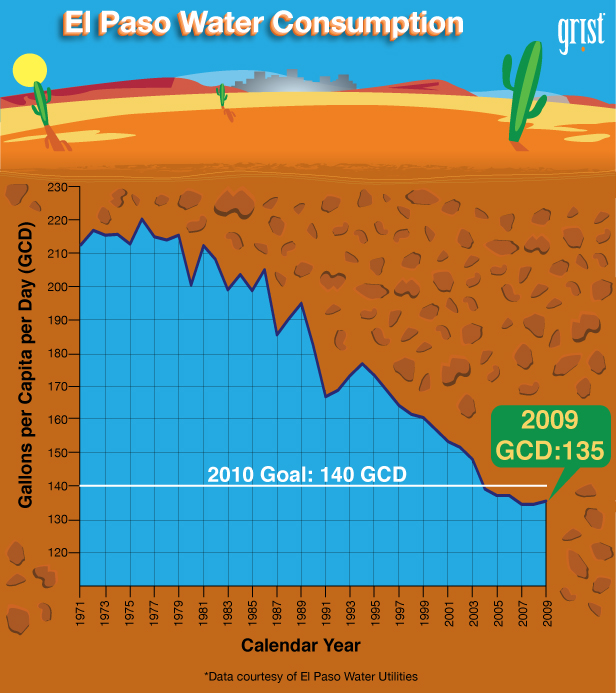

With the help of the conservation program, El Paso’s utility exceeded its goal of reducing per-capita water consumption 20 percent by 2000. The city reached a new goal of 140 per-capita gallons per day (another 12.5 percent reduction) four years ahead of schedule in 2006.

The dreamers

Ed Archuleta, 68, has been the president and CEO of the El Paso Water Utilities since 1989, overseeing water, wastewater, reclaimed water, and storm water service. Archuleta launched El Paso’s first water conservation program, which is still in effect today. Asking people to change their behavior today to preserve water resources in the future was a hard sell. Archuleta remembers facing irate customers brandishing their water bills at heated City Council meetings. To overcome resistance, Archuleta reached out to the community through the media, launched an education campaign, included community members in steering committees, and joined El Paso social clubs. “The failure of public utilities a lot of time is that they work on the concrete and steel, but they forget the people,” he says.

Ed Archuleta, 68, has been the president and CEO of the El Paso Water Utilities since 1989, overseeing water, wastewater, reclaimed water, and storm water service. Archuleta launched El Paso’s first water conservation program, which is still in effect today. Asking people to change their behavior today to preserve water resources in the future was a hard sell. Archuleta remembers facing irate customers brandishing their water bills at heated City Council meetings. To overcome resistance, Archuleta reached out to the community through the media, launched an education campaign, included community members in steering committees, and joined El Paso social clubs. “The failure of public utilities a lot of time is that they work on the concrete and steel, but they forget the people,” he says.

Charlie Edgren, 63, is the editorial page editor for the El Paso Times and the former editorial page editor at the now-defunct El Paso Herald-Post. Edgren and his colleagues in the local media enthusiastically jumped on board to help Archuleta’s water conservation campaign, publishing editorials and daily water consumption statistics, reminding people of the odd-even watering days schedule, and exposing water abusers. “People are so used to turning on a faucet and getting water that it frightened people a little to hear that it was really a finite resource,” Edgren says.

Bill Addington is the long-time water chair for the Sierra Club in El Paso and a familiar face at council meetings where he regularly holds elected officials’ feet to the fire. “I don’t believe they really believe in conservation,” he says.

Bill Addington is the long-time water chair for the Sierra Club in El Paso and a familiar face at council meetings where he regularly holds elected officials’ feet to the fire. “I don’t believe they really believe in conservation,” he says.

The money

The budget for El Paso’s conservation program is $1 million a year in staffing and marketing expenses. In addition, El Paso Water Utilities spent $2 million to $3 million a year on consumer rebates. Officials estimated that the program saved $400 million in construction cost by postponing treatment plant expansions that would have been necessary to supply a growing population with enough clean water.

The outcome

(Larger version.)Per capita consumption of water has gone down from 200 gallons per day in 1990 to the current 134 gallons per day. The reduction has allowed El Paso to produce the same amount of water now as it did 20 years ago despite a population growth of about 250,000. More importantly, the Hueco Bolson aquifer is no longer shrinking. Experts believe that if El Paso stays the course, 75 percent of its aquifer will still be there 100 years from now.

(Larger version.)Per capita consumption of water has gone down from 200 gallons per day in 1990 to the current 134 gallons per day. The reduction has allowed El Paso to produce the same amount of water now as it did 20 years ago despite a population growth of about 250,000. More importantly, the Hueco Bolson aquifer is no longer shrinking. Experts believe that if El Paso stays the course, 75 percent of its aquifer will still be there 100 years from now.

The copycats

El Paso’s downtown viewed from the Franklin Mountains, with Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, in the background.Photo: Marie GilotBy now, many cities have realized that conservation is the most cost-effective way to stretch water supplies, and they have turned to El Paso for guidance. What has made El Paso a model for water conservation is that despite its arid location and modest means (over a quarter of the population live below the poverty level), the city has managed to sustain its comprehensive approach to water conservation. Now, with a Texas law mandating that all cities draft a water conservation plan, public officials are looking

El Paso’s downtown viewed from the Franklin Mountains, with Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, in the background.Photo: Marie GilotBy now, many cities have realized that conservation is the most cost-effective way to stretch water supplies, and they have turned to El Paso for guidance. What has made El Paso a model for water conservation is that despite its arid location and modest means (over a quarter of the population live below the poverty level), the city has managed to sustain its comprehensive approach to water conservation. Now, with a Texas law mandating that all cities draft a water conservation plan, public officials are looking

at El Paso’s proven methods. San Antonio, Texas, Albuquerque, N.M., and several smaller towns studied El Paso’s approach, says Ed Archuleta, who studied water conservation programs in Tucson and Phoenix when he was designing El Paso’s initiative. “You don’t always have to redesign the wheel,” he says.