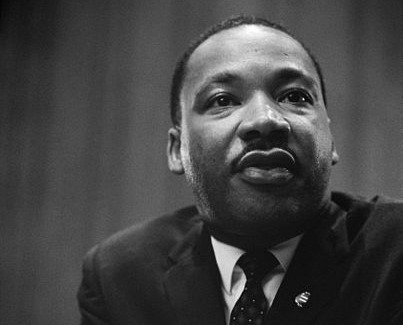

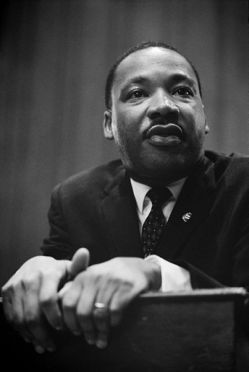

Marion S. Trikosko

In July 2008, I was in Atlanta trying to learn how to be an anthropologist of bicycling. Looking for clues, I went to the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site, and I found myself overwhelmed by the power of Dr. King’s words. He summarized our American situation, argued for hope, and it all sang with truth. I stumbled around the exhibit, blinded by tears, knowing the horrible conclusion awaiting me at the end.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.

I had of course heard Dr. King’s speeches before this, but I thought of him as a figure in history. I knew that Dr. King fought tirelessly to secure African American equality, but I didn’t understand that through this he sought to show us the connections between racial injustice and all injustice. A spiritual leader as well as a cosmopolitan intellectual, he drew on the ideas of Hegel and Gandhi and urged understanding between groups divided by hate and ignorance. His words hit me so hard on that day; they came alive and filled my heart.

Now, in order to answer the question, “Where do we go from here?” which is our theme, we must first honestly recognize where we are now.

In 2008, I was just beginning to see the fight that lay before me as a bicycle advocate and researcher. I had a growing awareness of the cultural barriers to sustainable transportation in Southern California, the anger bicycling bodies stirred with our audacity to use public streets. But it was a stranger’s death that opened my eyes to a deeper level of disempowerment in bicycling. Near my hometown, San Juan Capistrano, on a night in October 2007, a young woman who was driving drunk hopped the curb in her car and struck José Umberto Barranco, who was riding home on the sidewalk late one night from his job in the kitchen at a Denny’s. This stretch of road had very infrequent bus service, once an hour and none late at night, and perhaps Barranco could not afford a car, so he commuted by bike. The Los Angeles Times reported that, “Barranco had planned to spend Christmas with his wife, 13-year-old son, and 8-year-old daughter in the central Mexican state of Morelos, family members said. He hadn’t seen them in nearly two years, they said.”

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations.

For me, bicycling is a choice. For others, who may never escape economic exploitation no matter how hard they work or how hard they hope, bicycling is a necessary evil. Bicycling has a double negative image: Either you bike because you’re an entitled jerk, or you bike because you’re the scum of the Earth. In January 2008, I heard fear in the voices of homeowners in Long Beach who opposed a bike lane on their street. They said they didn’t want to invite people to “camp out” in their historic neighborhood. I felt hate in the squealing of brakes and revving of engines as people swerved their cars around me as I biked to school.

Let us therefore continue our triumphant march to the realization of the American dream. Let us march on segregated housing until every ghetto of social and economic oppression dissolves, and Negros and whites live side by side in decent, safe, and sanitary housing.

I grew up in a town where the Latino families on my side of the railroad tracks were seen as a menace by white residents on the other side, who pulled nearly all the white children out of the local school. When I joined students from the other local elementary school in junior high, a girl informed me that I had attended “the Mexican school.” It wasn’t until years later that it occurred to me that her parents may have been using a term left over from the era of segregated schools in Orange County. When I was a child, I used to watch white recreational cyclists ride past my family’s apartment, using our neighborhood as a connector between regional bike paths. When I got involved in the bike movement in Los Angeles in September 2008, I started hearing advocates talk about being “second-class citizens” on car-dominated streets. I was struck by the irony of hearing white men and women use that term. I wondered how many of them were the products of our society’s informal segregation, where Americans arrange themselves in suburban enclaves according to race and income. I heard many people share stories about how they had loved the freedom of biking when they were children.

It’s nonsense to urge people, oppressed people, to love their oppressors in an affectionate sense. I’m talking about something much deeper. I’m talking about a sort of understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill for all men.

It is true that the vulnerability of our bodies makes even privileged individuals into potential victims, but I can see why bicyclists might sound like entitled jerks, acting like their right to the road means taking it over. But knowing what I do about how useful bicycles are, both for people with tight budgets and for our future in the face of the very big climate problem we share, I think it’s unfair to dismiss bicycling because of the behavior of a few clueless individuals. What we need are more voices to drown out the ignorance of the few.

And I’m simply saying that more and more, we’ve got to begin to ask questions about the whole society. We are called upon to help the discouraged beggars in life’s marketplace … But one day we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.

If our streets are structured in such a way that those bodies traveling outside of cars cannot pass safely, what have we done but created an edifice which produces beggars? Bicyclists are portrayed as selfish, choosing to use bikes and wanting to impose changes on the streets. But we see ourselves as working to change our society’s destructive transportation habits. Many of us in the bike movement are concerned about the big changes coming to our planet. As temperatures rise and we face the downsides of oil dependency, we see the bicycle as way to lessen our impact on the environment. I also see bicycling as a way to connect people, which is something our society needs desperately.

Let us be dissatisfied until the tragic walls that separate the outer city of wealth and comfort from the inner city of poverty and despair shall be crushed by the battering rams of the forces of justice.

Because I know suburban segregation firsthand, I prefer to live in cities. More and more Americans are like me, biracial, bicultural, uninterested in moving to an isolated citadel accessible only by SUV. I want to be surrounded by diversity. Sadly, more and more it seems like urban diversity cannot be taken for granted. What would Dr. King think of the trend toward expensive inner cities as America’s poor move to the suburbs? Surely he would argue that this is not the right way, that as long as we stay divided, we have done nothing but set up the same house of cards in a different configuration. This us vs. them mentality that we create through segregating our communities bleeds into transportation.

Darkness cannot put out darkness; only light can do that.

The burden is on the bike movement to show how our goals are not different from the goals of social justice movements. We want all people to benefit from bicycling. Good for the body, good for the city, good for the planet. But it’s hard to show this when we get dismissed as a selfish group of gentrifiers. We need to work together to confront the inequality that our cities are reproducing by using bike infrastructure as a means to raise property values and push out the poor. Too many American children grow up in isolation from other ways of life, and it is not hard to see how this might affect our ability to understand each other as adults.

Yes, we need a chart; we need a compass; indeed, we need some North Star to guide us into a future shrouded with impenetrable uncertainties.

The bicycle is not something that belongs to one group or subculture; it’s a useful object that takes many different forms in social and cultural life. And it crosses boundaries. When you’re on a bike, you see openings in the city, places where you can slip between streets and neighborhoods. Can the bicycle unite movements as well? Bicycling should be something that people of all ages, races, classes, genders can use to stay connected with their neighborhoods and improve their health. If we don’t get a diverse coalition involved in the move to redesign American cities to be more sustainable, we are neglecting something important for all of us: the shape of our streets.

We must walk on in the days ahead with an audacious faith in the future.

We need a human infrastructure to connect our divided communities. We need bike advocates to go to neighborhood groups and come to a consensus about livability, not as outsiders imposing on longstanding communities from outside, but as engaged leaders in the shift we must make to a cleaner future. Inspired by the work of Dr. King and all the people who have heeded his call, we can bring just conditions of social equality to our country, our streets, and our planet. But we have to work together.

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

Thank you, Dr. King, for sharing your vision with us all.

Quotes from A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Edited by Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard. You should listen to his speeches, though, because as Dr. King remarked in the introduction to a collection of his sermons, there’s a difference between words meant to be heard and words meant to be read.