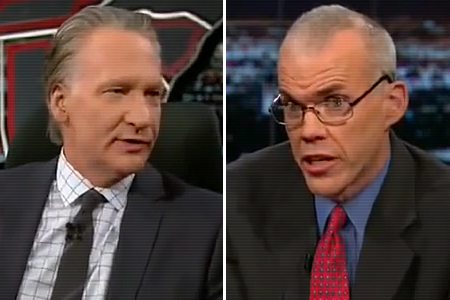

Bill McKibben was on Real Time with Bill Maher last Friday. Watch:

[protected-iframe id=”1f07db6615cec67fd9ccbd38f24651b1-5104299-30178935″ info=”http://www.liveleak.com/ll_embed?f=f668d0d81af9″ width=”470″ height=”240″ frameborder=”0″]

Wasn’t he great? I love this line: “We only have so many major physical features on the planet, four or five, and you don’t really want to just start breaking them. That’s why we can’t have nice things.”

From my limited experience on television, I’ve learned what should be obvious: It is extremely difficult to keep your head in a live, improvised setting. Remaining calm and articulate when your adrenaline is flowing — and it is flowing — takes real grace. So the best part about Bill’s performance is simply that he radiates authority, especially relative to the conserva-twerp he has so much fun swatting down.

On TV, success or failure ultimately depends on affect. The vast majority of viewers have no sense of the underlying facts and are simply responding to who appears more confident and who seems to have the moral high ground. On that score, Bill is unimpeachable — Gore without the baggage.

Now, all that said, I am a dirty blogger, so I can’t just leave it there. Gotta do a little Tuesday-afternoon quarterbacking. It’s a compulsion.

——

Conversations about climate change in the U.S. tend to devolve into uncertainty vs. certainty. The panel discussion that followed Bill’s initial remarks demonstrates how it happens.

Conserva-twerp Will Cain (do they make these guys in a factory?) faithfully delivered the conservative attack, which is twofold. First, they argue that solutions proposed by climate hawks will strangle the economy — Cain compares them to a tourniquet. Then they ask, “Shouldn’t you be really certain before you ask us to do something like that? Are you that certain? Because I heard scientists are still arguing over stuff.”

Climate hawks, in my experience, tend to respond with some variation of, “Yes! Scientific consensus! We’re certain!”

Look, though, at how this allows conservatives to frame the discussion: “Are you so certain that we have to do this awful thing?” “Yes, we’re certain you have to do this awful thing!”

It’s ineffective (and objectionable) in two ways. First, there’s the implication that, if the science is valid, it dictates a certain policy response. As Bill puts it, “This is not a matter of politics, it’s a matter of physics.”

That strikes a discordant note with me. It is a matter of politics. What else could it be? That’s how we make collective decisions! There’s something off-putting about anyone, no matter who, presenting a set of facts and saying, “This leaves us no choice but to do what I advocate.” There is no set of facts that allows — or should allow — anyone to skip past the process of democratic deliberation.

Second, when the response to “it’ll cost too much” is “but we have to do it,” climate hawks implicitly concede the cost argument. And I don’t think there’s enough scientific consensus in the world to force people to do something they think will strangle the economy.

The case for climate action needs to be made from within politics and economics, taking into account competing values, worldviews, and degrees of risk tolerance. I don’t want climate hawks to retreat from that scrum by trying to use science as a trump card.

The thing is, the argument for climate action can be made from within politics. At least I think it can.

——

Cain has one strong angle in the discussion. At one point he’s asked, effectively, what unanticipated technological advances could save us from climate change (or “replace Iowa,” as Bill says). Cain says, “I have humility. I don’t know. I would suggest that you don’t know what things will be like in 100 years either.”

This line has intellectual appeal because it’s true. We don’t know exactly what the world will look like in 100 years. We’d be crazy to say we do.

Here’s how I would address that line of attack, assuming that I had way more time to respond than Bill did, was way better at thinking on my feet than I actually am, and would ever get invited on Maher’s show in the first place … so, y’know, in my fantasies:

Will is right — we don’t know what the world will look like in 100 years. But that doesn’t mean what he thinks it means.

Right now, all our best science agrees on a few broad things: It’s going to get hotter, that heat is going to mess with natural systems, and the effects on us humans, especially the poorest and most vulnerable humans, will be awful. We have more than enough information to know that there’s a serious threat and that we need to do something about it.

But when it comes to predicting, say, specific levels of precipitation in Iowa, we’re still stuck with a wide range of possibilities. We’re pretty sure precipitation patterns will substantially change, what with all this new energy being trapped in the atmosphere. But can we say exactly how often it will rain in Iowa in 2100? No.

What Will doesn’t seem to understand is that this kind of uncertainty isn’t a reason to sit back on our laurels and wait for more information. It’s the opposite! After all, if there’s a 50 percent chance things could turn out better than our best estimates, there’s also a 50 percent chance they could turn out worse. And if you’ve seen our best estimates, you know that “worse” should give you nightmares.

If I told you your house had a 50 percent chance of burning down, would you say, “Get back to me when you’re sure”? No: you’d buy insurance! Scientists are telling us there’s a high-and-rising chance of serious, even catastrophic climate disruption. So we need to buy some insurance. That means diversifying our energy sources and ruggedizing our food, water, and transportation systems. We need to be, in a real sense, ready for anything. Oh, and we need to stop raising the chances of catastrophe by carbon-loading the atmosphere.

Being ready for anything in the face of uncertainty costs more money in the short term. But it costs a hell of a lot less than not being ready when the time comes. Just ask New Orleans.

Of course, this is just my two recent posts on deep uncertainty rehashed. And I freely admit it’s too long and wonky for a show like Maher’s. But still, I think climate hawks should start exploring how to communicate along these lines. Somehow, we’ve got to convey that uncertainty is not our friend, that this foggy, stormy future we’re sailing into is reason to batten down the hatches. We don’t know exactly what’s going to happen … and that is terrifying.

And we’ve got to convey that a robust, precautionary approach focused on resilience is the fiscally prudent path, that spending more now on diversification and ruggedization is smarter than risking everything by placing all our bets on our current, brittle system.

I’m not the best at figuring out folksy ways to say these things (obviously), but somebody needs to translate this kind of stuff into folksy aphorisms, quick.

Anyway, to loop back around, congrats to Bill for a virtuoso performance before a large and persuadable audience. How often do us climate hawks get to celebrate such things?

Editor’s note: Bill McKibben serves on Grist’s board of directors.