Too many climate headlines sound alike: “Polar ice cap melting faster than expected,” “Scientific consensus stronger than ever,” “Pacific island soon to be underwater,” etc. But this recent one stood out: “Just 90 companies caused two-thirds of man-made global warming emissions.” That’s from a Guardian story about new research in the journal Climatic Change, in which Richard Heede calculated the greenhouse gas contributions of major companies since the Industrial Revolution.

The news excited at least one legal scholar. In a blog post for the Center for Progressive Reform, American University law professor David Hunter calls the study “a potential game-changer” because it could make it easier for climate change’s victims to sue its perpetrators. Hunter writes:

Courts need no longer fear that it would be impossible to untangle the private sector’s historical contributions to climate change or unfair to make oil companies, for example, pay for all climate-related damages. A clear formula now exists for allocating at least a significant percentage of the costs of climate change to those companies that benefited most from the public nuisance created by their emissions. Take, for example, the costs of moving the Inuit village of Kivalina, which attempted to sue several of the top polluters for the anticipated costs of relocating their village as a result of climate change. Those costs could now be allocated to the major fossil fuel companies based on their historical contributions to the problem.

From this you might think that if you and your neighbors are harmed by extreme flooding or forest fires, you could band together and sue the companies responsible for climate change. That is unrealistic.

Looking at the list of top greenhouse gas polluters, 31 are state-owned companies and nine are government-run industries. Even if you could sue Saudi Aramco (#3) or Russia’s Gazprom (#5) for climate change in an American court, good luck getting them to pay your judgment if you win.

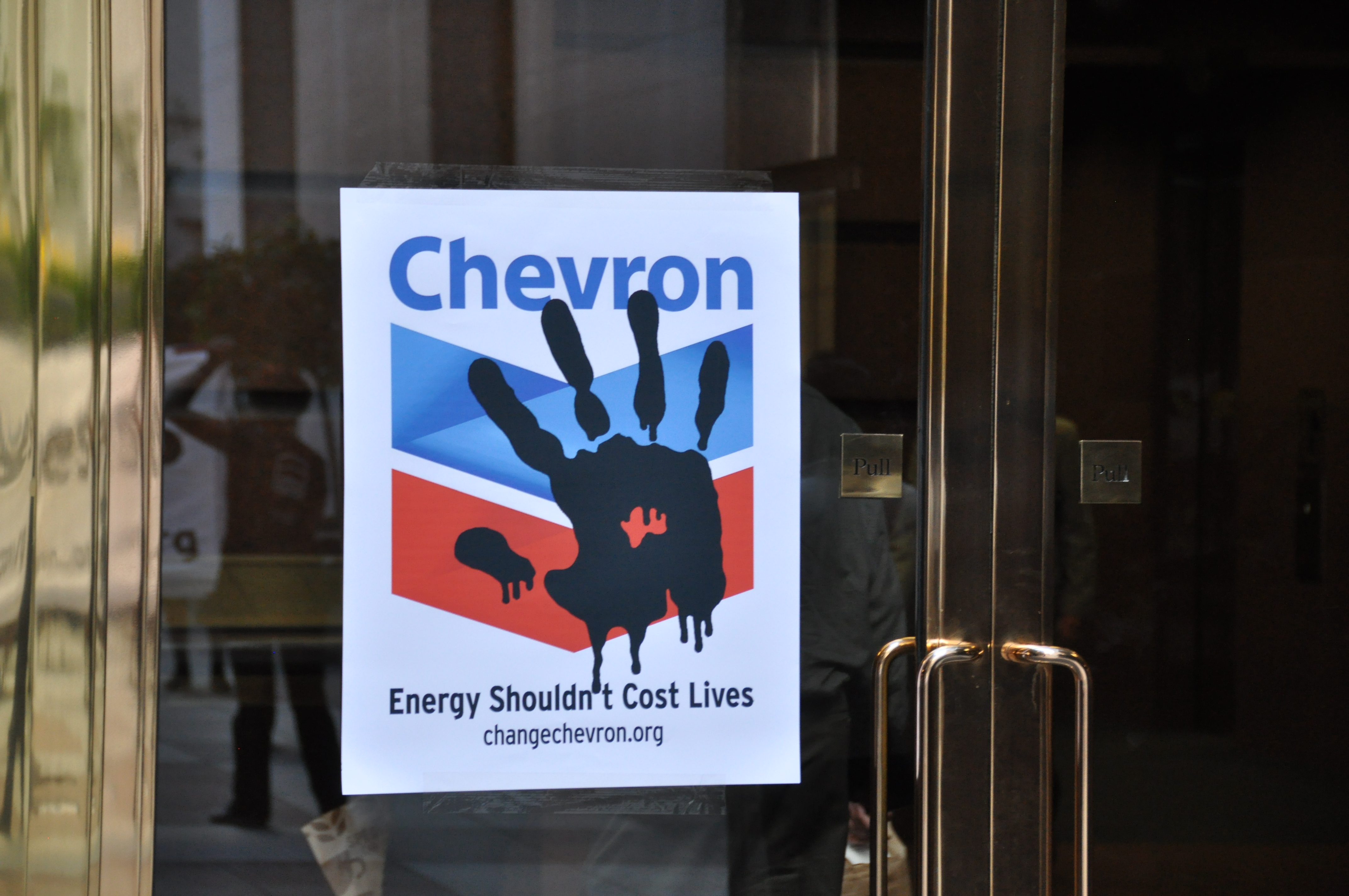

What about publicly held companies based in the U.S.? Could you sue Chevron (#1) and ExxonMobil (#2) for their proportional responsibility for your damages, which would be 3.52 percent and 3.22 percent, respectively?

No, you can’t, at least not in federal court. According to environmental law experts, including those at leading environmental organizations, previous court rulings have made it clear that there is no avenue to do so.

Ironically, this is a downside of the Supreme Court’s landmark 2007 ruling Massachusetts v. EPA, which held that greenhouse gases are pollutants under the Clean Air Act, and therefore subject to EPA regulation. That was good news, paving the way for EPA rules limiting CO2 emissions. But it also led to American Electric Power v. Connecticut, a 2011 Supreme Court decision that found states cannot sue companies for emitting greenhouse gases. In that case, a consortium of Northeastern states and land trusts sued Midwestern power plants seeking a federal court order requiring them to curtail their CO2 emissions. The Supreme Court ruled that because CO2 is a pollutant under the Clean Air Act, it is the EPA’s job, and not the courts’, to regulate interstate CO2 pollution.

When a victim of pollution sues a polluter from another state in federal court, it is governed by what is known as federal common law. This is the body of jurisprudence governing torts that are not written in federal law. If Ohio dumps its garbage in Pennsylvania’s state parks, Pennsylvania can sue Ohio in federal court, despite the absence of a law specifically forbidding Ohio’s behavior. But if Congress does pass such a law, then the courts will say federal common law has been “displaced” by the congressional regulation, and Pennsylvania must seek its remedy from the duly empowered federal agency.

Precisely because the Supreme Court had already held that gases causing climate change fall under the Clean Air Act, the justices unanimously ruled in AEP v. Connecticut that the Clean Air Act displaces federal common law and states, citizens, or other entities cannot sue the companies causing climate change.

“American Electric Power v. EPA is an important and sometimes overlooked decision,” says Richard Frank, director of the California Environmental Law & Policy Center at the University of California, Davis. “In the area of climate change, at least, private parties suing under common law theories like the public nuisance doctrine is displaced by the Clean Air Act. If the Supreme Court hadn’t reached the conclusion it did in Massachusetts v. EPA, it would have been much harder for the Supreme Court to reach the displacement decision.”

The Inuit villagers of Kivalina, Alaska, meanwhile, have tried suing not to stop pollution but to collect monetary damages from polluters. Their town is disappearing due to rising sea levels, and it will cost around $400 million to relocate it to higher ground, so in 2008 they filed suit in federal court against 24 of the world’s largest oil, coal, and power companies for causing climate change. Their suit was dismissed in district court and they lost their appeal to the 9th Circuit Court in 2012. Even though the Clean Air Act doesn’t provide monetary damages to victims of pollution, the 9th Circuit held that the displacement ruling in AEP v. Connecticut means that climate change can only be addressed by the legislative and executive branches.

Hunter acknowledges, when asked, that you cannot sue climate polluters in federal court. But he notes, as do others, that the federal court precedents do not apply to state courts. So you could bring a suit against a greenhouse gas emitter at the state level. “This study does nothing to change the 9th Circuit preemption decision,” Hunter concedes. “The case did not address state common law claims, however, and Kivalina or similarly situated plaintiffs still have the option to file state law claims.”

However, each state has its own laws and its own tradition of common law governing torts. So in at least some state courts, you would get the same answer that Connecticut did from the Supreme Court. “The Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act both have a clause saying nothing in this law pushes aside state common law,” says David Doniger, policy director of NRDC’s climate and clean air program. “But many states say, ‘We have state laws that regulate pollution, if you’re in compliance with your permits and applicable rules, you can’t be sued.’ Other states say it doesn’t matter if you’re causing harm, you can be sued.”

A state court would also have to buy the idea that climate change is the fault of these companies in particular, not society as a whole. Some experts are skeptical. “Those companies were selling their products to all of us, so it strikes me as a bit disingenuous to say they alone are to blame,” says Holly Doremus, director of the environmental law program at U.C. Berkeley.

And let’s say your house was damaged by a hurricane. You would have to convince a judge and jury that the specific hurricane was caused by climate change. Just because climate change makes storms stronger and more frequent doesn’t mean you can blame oil companies for any given storm in a court of law.

“I don’t think this study will make much difference,” says Doremus. “Getting a judgment against emitters on the merits turns out to be harder than estimating the extent of the damages.”

Heede’s research has other applications, of course. Ideally, American policymakers would take its findings into account when devising a cap-and-trade bill or carbon tax, and international negotiators would consider it when crafting a climate treaty.

Also, since neither the perpetrators nor the victims of climate change are limited to the U.S., the study has potential to help with lawsuits in other countries with totally different laws and legal standards. “The liability for climate change may not emerge in U.S. litigation at all,” says Hunter. “It may arise in legal actions brought in other countries where the preemption argument would not be available. In those jurisdictions, arguments for corporate liability are clearly strengthened by this study.”

So when it comes to climate lawsuits, the most litigious country on earth might actually miss out on most of the fun.