A version of this article originally appeared on Grip on Climate.

David Roberts here at Grist and Stephen Lacey at Climate Progress kicked off a good discussion last week about the roles of “yes” and “no” in climate work. This would-be schism dominates Climate Solutions’ strategy sessions, so I must weigh in.

David Roberts here at Grist and Stephen Lacey at Climate Progress kicked off a good discussion last week about the roles of “yes” and “no” in climate work. This would-be schism dominates Climate Solutions’ strategy sessions, so I must weigh in.

Climate Solutions is a “yes” outfit. Roberts nailed our MO: We’re all about “forging of opportunistic coalitions.” We accept “compromise, tedium, and endless setbacks.” Roberts says “it’s just more fun to rage against The Man,” but we’re actually to the point where we revel in “the boring of hard boards.” Our mission statement even makes it sound romantic, adventurous: “ … galvanizing leadership, growing investment, and bridging divides”!

Here’s the thing, though: With no meaningful climate policy commitment — no binding emission limits, no carbon pricing, not even a clean energy standard — the awesome work of building a clean energy economy is proceeding in parallel to the unfolding disaster of climate disruption, rather preventing it. We can say “yes” ’til we’re blue in the face, but we can’t call it “climate solutions” unless we stop the beast.

A local example: Here in Seattle, we made a commitment in 2000 to power our community with zero net carbon emissions. We sold our share of a big coal plant (which is now on its way to retirement). We let our gas combustion turbine contract expire. We doubled down on efficiency. We made the anchor investment in the region’s first big wind project. For the little remnant of emissions we couldn’t eliminate (utility maintenance vehicles, spot market purchases, etc.), we bought high-quality offsets. Saying “no” to carbon in our power supply was a launching pad for saying “yes” to a clean energy economy.

By selling our share in that coal plant, we scrubbed about 400,000 tons of coal a year out of our energy footprint. Sweet. But if the current coal export proposals in the Northwest are fully developed, we would ship over 400,000 tons of coal a day through our communities to be burned in Asia (a third of it right through the middle of our iconic Olympic Sculpture Park on Seattle’s waterfront). Our clean energy economy, as my colleague Ross Macfarlane colorfully says, would be but “a hood ornament on the Hummer of fossil fuel addiction.” Our brave local “yes” would be a joke.

The point here is not just that the bad stuff will overwhelm us if we fail to stop it (though that point alone is plenty to justify “no”). It’s that unchecked expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure undermines the credibility of solutions. “Yes” to climate solutions without “no” to these “game-ending” investments comes off as silly, sentimental, tokenistic.

We work with a lot of state and local elected officials who take on climate commitments. Almost invariably, skeptical reporters ask them something to the effect of, “C’mon, what difference will it make? Our emissions are a miniscule fraction of the problem. We could reduce our carbon footprint to zero and we’ll still have the same climate impacts. Isn’t this local action just symbolic?”

A good answer goes something like, “We’re not fighting climate change alone. Our city is joining with umpty-ump other communities, nations, and businesses around the world to deliver solutions. We’re doing our part and pressing our national leaders for stronger action. We’re proving up solutions that can work everywhere. And we’re making this a better place to live and work by [fill in co-benefits here].”

This is a beautiful story, and we’ve done much to make it true. But nobody is going to hear it over the din of coal trains rumbling through town all day. If we take all the coal we don’t burn, and a couple of orders of magnitude more, and ship it through our communities to promote global fossil fuel dependence, how can we say with a straight face that we’re serious about solutions? Yes is bunk without no.

Yes also feeds no. It’s like an immune-system booster — building resilience and increasing our capacity to resist fossil fuel development. In Bellingham, Wash., for example, the largest and most powerful business association is not the chamber of commerce but Sustainable Connections. This community has such a strong investment in “yes” that the idea of becoming a coal export hub seems like an alien invasion. In a terrific NPR story, Julie Trimingham of Coal Train Facts says movingly: “It’s almost inconceivable that there would be a plan afoot to change this part of the world to a coal export facility. It seems ironic or cruel, or misguided at best.”

Even in Longview, Wash., an industrial port community targeted for coal export, “yes” holds a powerful allure. The vision statement in “Turning Point” [PDF], its local economic development strategic plan, says the community “will transition from a natural resource dependent economy, embrace higher value projects, and raise its profile within a broader regional market.” The coal export battle there will test the resolve and hope in that community for the “yes” they’ve imagined. If they believe in it, they’ll say no to coal export, which is roughly the exact opposite of their vision statement.

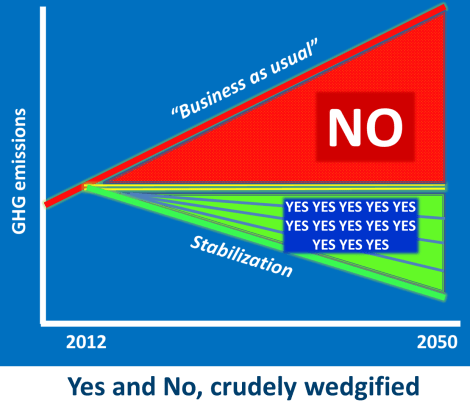

Yes and no are interdependent, but they are not symmetrical with respect to the pace and scale of the climate challenge. The climate “game” must be won over the long haul. The winning strategy is a zillion yeses, driving an inherently slow transition. But the game can be lost very quickly — Jim Hansen’s point in “Game Over for the Climate,” and the bright bottom line in the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook. Yes is a patient, incremental thing. But the no we need to muster on tar sands and coal export is immediate and uncompromising.

Yet, while their roles and applications differ, yes and no aren’t competing philosophies or alternative psychographics. Our political culture drives us toward niches, pressuring us to identify as yes or no types. But if you want to be an effective climate advocate (or parent), you have to wield both. Yes and no are the interdependent and mutually reinforcing faces of responsible action.

The more successfully we say no to fossil fuels, the more we open space for the growth of the clean energy economy we envision. And as we open it, we need to fill it. We have a better idea than Peabody and ExxonMobil about what a good future is, and we have to keep delivering on it.

When we affirm and invest in our vision, we fortify our defense against the fossil fuel onslaught. The more “yes” we say and do, the more credibly we can fight fossil fuel development with the claim: “We can do better” — a core message in the coal export campaign.

Yes without no is lame. No one will believe in the power of our clean energy vision if we let the fossil fuel juggernaut mow us down and wreck the climate.

And no without yes is adolescence. The only way to prove we can do better is to … do better.