In Portland, food carts fill a parking lot with lines stretching onto the sidewalk. (Photo by camknows.)

Whatever you’re craving, you can probably find it on sale in a parking lot in Portland. From barbecued jackfruit pie, to foie gras over potato chips and kimchi quesadillas, it’s no coincidence Portland has been heralded as a world-class purveyor of street food.

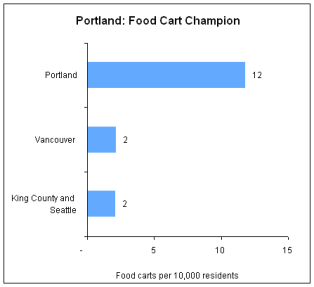

Street food is smart for sustainability: It makes urban living more desirable to many, improves neighborhood walkability, provides affordable dining options, and opens doors for diverse entrepreneurs (many of whom also see sustainably produced ingredients as key). And recent attention to the Rose City’s food cart scene has made other nearby cities green with envy. Take Seattle and Vancouver, B.C., for example. Both had laws limiting food cart cuisine until recently, and now both have tossed those rules in the dumpster, hoping to unleash legions of new small businesses.

Let’s compare and contrast these three West Coast cities’ approaches to street food:

Portland: ground zero

Street food in the Rose City traces its roots back to the 1970s, but it really started heating up a few years ago when the economic downturn dovetailed with the city’s reputation as a foodie mecca. Today, Portland boasts nearly 700 food carts, thanks to the city’s laissez-faire approach.

Street food in the Rose City traces its roots back to the 1970s, but it really started heating up a few years ago when the economic downturn dovetailed with the city’s reputation as a foodie mecca. Today, Portland boasts nearly 700 food carts, thanks to the city’s laissez-faire approach.

Operating in semi-permanent “pods” on private parking lots, food carts have become go-to destinations for workers looking for cheap lunches, tourists wanting to sample street-side dining, and after-bar crowds. A profusion of carts, loads of hungry supporters, and the city’s long track record of encouraging these local businesses all help explain why Portland’s policies have become so welcoming to merchants of dishes like Potato Champion’s poutine — a popular mound of cheese curds and gravy over French fries.

Because pods operate on private property, vendors avoid regulations regarding street usage. And the city often turns a blind eye when lines spill onto the sidewalk; they’ll respond to complaints but don’t tend to police violators otherwise. And Portland city officials don’t bother vendors who leave their carts in the same spots for months at a time, either.

Still, Portland vendors continue to push the limits. As more carts settle in for long stays, many are building adjoining structures, like decks, which raise safety concerns for the city. Nonetheless, Portland has been accommodating in its rules. The state of Oregon has, too; it’s on the brink of granting its first liquor license to a food cart. When problems arise in Portland’s cart pods, the city’s policy has been to resolve the problems without unnecessarily constraining the booming industry. Vendors are even starting to gain political clout: They recently teamed up to form a new advocacy group.

Vancouver: early growth

Vancouver has a hungry street food crowd, but the city has capped the number of vendors. (Photo by InvokeMedia.)

Vancouver, B.C., has had street food since the early 1970s, but it wasn’t much. City rules limited vendors to packaged consumables and hot dogs. In 2009, however, the city cut the red tape, allowing mobile vendors to sell what they wanted, as long as they were in compliance with the provincial health authority.

Afraid of opening the floodgates wide, the city has moved slowly. In 2010, a city-appointed panel picked 17 vendors to permit in the Vancouver’s downtown area as part of a pilot program. The carts now vend at designated sidewalk sites, picked by the city, or choose their own street parking location as long as they meet guidelines such as sidewalk accessibility. In both cases, vendors have to list their locations on permits and cannot venture elsewhere.

Outside of downtown, carts must be on the move daily, and vendors face even stricter regulations beyond city boundaries. Similarly, Vancouver vendors cannot sell food from private property, as Portland’s do, and they are required to use a licensed commissary, or shared kitchen, for food storage and prep. The Oregon Department of Health, in stark contrast, treats mobile kitchens as sufficient, dispensing with the commissary requirement.

The preliminary results have been positive; food trucks downtown are popular with the lunchtime crowd. The city ended the pilot in 2011, adding 19 carts that year and 12 more in early 2012. (Interestingly, the city awarded new permits partly based on carts’ use of organic, local, and nutritious ingredients.) They plan to add 60 more by 2014, bringing the total to 130. But the program has been limited to downtown, preventing carts from entering surrounding neighborhoods where the lucrative nightlife market awaits.

Officials credit early success to the minimization of red tape. And it’s true that Vancouver’s regulations are less restrictive than before: The city’s efforts to both designate sidewalk stalls and allow vendors to find their own locations make it easy for carts to launch quickly, while not overly limiting locations. Crucially, city officials have expressed interest in lifting restrictions outside downtown — and perhaps even lifting the ban on vending from private property.

But unless Vancouver changes its official plans, in five years, the city will have introduced only 100 carts, fewer than Portland added in 2010 alone.

Seattle: still lukewarm

Aloha tacos from Seattle's Marination Mobile. (Photo by ddaarryynn.)

Like Vancouver, the city of Seattle spent years limiting carts to hot dogs, popcorn, and coffee at sports stadiums. Several years ago, however, vendors started to sidestep the laws by setting up shop on private property and street food started to grow.

Then, in July 2011, the city council made a bold move: It passed regulations to encourage street food. Councilors lifted restrictions on what carts can sell and created new guidelines for where they can park. Unlike Vancouver, Seattle placed the onus on vendors to find locations that meet the guidelines (such as leaving adequate throughways for pedestrians).

The city also gave restaurants and bars a veto over mobile vendors operating within 50 feet of their front doors. At the same time, they tripled fees for permits to nearly $1,000 dollars (about the same as in Portland).

Have the rule changes panned out? Not yet. Since July, the city issued only seven new permits for food trucks — defined in Seattle as self-powered vehicles with kitchens onboard — to vend from public streets, and six permits for food carts. In fact, the number of food cart permits actually have dropped since the new regulations took effect.

Seattle has pockets of success, such as South Lake Union, a quickly developing neighborhood just north of downtown, but cart vendors rarely venture into downtown Seattle, except for farmers markets and special events.

The city also requires that carts return to a commissary kitchen every day, prohibit them from remaining overnight, and prevent them from being near other food businesses.

Of course, it takes about two months to get permitting for a cart and its site, and most of the last eight months have been cold and wet: street foods’ off season. Perhaps the summer of 2012 will bring a flowering of carts in the Emerald City?

Hungry yet?

It doesn’t look like either Seattle or Vancouver will rival Portland for the title of “Food Cart Champion” any time soon. But both cities clearly recognize the benefit of street food and are taking moderate steps. Despite the remaining hurdles, Seattle and Vancouver could have tasty futures ahead of them.

What about your city? Let us know in the comments below.

A version of this post originally appeared on Sightline Daily as part of a series on simple sustainability solutions that are outlawed in many places.