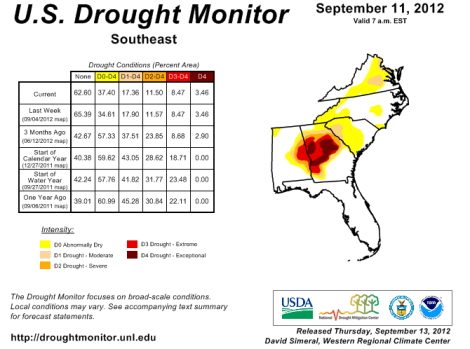

Georgia, like many other states, is suffering from the drought. Here’s Drought Monitor’s assessment of the current state of drought in the southeast; Georgia is affected far more than any other state in the region.

Image courtesy of Drought Monitor.

More than half of the state is experiencing at least moderate drought; 17 percent is seeing “exceptional” conditions.

Atlanta, in two weeks.

If you ask state officials, however, you get the real story: Drought? Whatsa drought?

Environmentalists, scientists and farmers point to places like the Flint [River], as well as reservoir levels and stream and rainfall data as proof of drought. Republican Gov. Nathan Deal and much of the business community contend that there is no drought. Unlike his predecessor, Deal has yet to declare one.

The state’s resistance to more drastic measures stems from its desire to protect its business-friendly image, critics say. “Atlanta is the brightest symbol of the ‘New South,’ and the Southern miracle depends on the use of natural resources,” said Gordon Rogers, executive director of Flint Riverkeeper, an environmental group. “And the key resource is water.”

So the logic goes: For Georgia to attract investment, people have to believe that it has abundant resources. And if the state declares drought, people might think that there’s no water and no one will ever move there, or something. Seems smart. North Carolina smart.

The state is also trying to avoid hammering the water-intensive landscaping industry.

The last drought, in 2007-08, hit metro Atlanta harder than this one. So, the state took dire steps to ensure adequate water supplies.

Then-Gov. Sonny Perdue, a Republican, rallied folks to pray for rain. But Georgians say what mattered most was that Perdue talked up the drought. People tweaked their daily lives to conserve water, like taking shorter showers or turning off the tap when brushing their teeth.

More controversially, Perdue made an official drought declaration and imposed strict restrictions on how much and when people could water their lawns. Along with the recession, the watering ban pummeled one of the state’s largest industries, so-called urban agriculture, which includes turf grass and landscaping, leading to layoffs and bankruptcies.

This time, the $8-billion-a-year industry was spared what Georgia Agribusiness Council President Bryan Tolar calls the “knee-jerk reaction” of the watering ban.

Tolar’s got it right. When a state is more than half in drought, suggesting that maybe everyone cut back on water use is a knee-jerk response. Similarly, when you are on fire, people are far too quick to stop, drop, and roll.

It is much easier to stick your head in the sand when your state has been dried into dust.