This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In December 2021, President Joe Biden signed an executive order requiring the 600,000-vehicle federal fleet to shift to zero-emissions by 2035 as part of an effort to leverage government buying power to “catalyze America’s clean energy economy.” The massive federal purchase is meant to help manufacturers move away from internal combustion engines and toward electric vehicle production.

If Biden has his way, half of the 17 million cars and trucks sold in the United States in 2030 will be electric. And even if his order is overturned by a later administration, the International Energy Agency predicts that market-driven demand will lead to similar numbers of new electric vehicles on the road, substantially decreasing tailpipe emissions, urban pollution and overall greenhouse gas emissions — as long as fossil fuels don’t dominate the grids charging the cars.

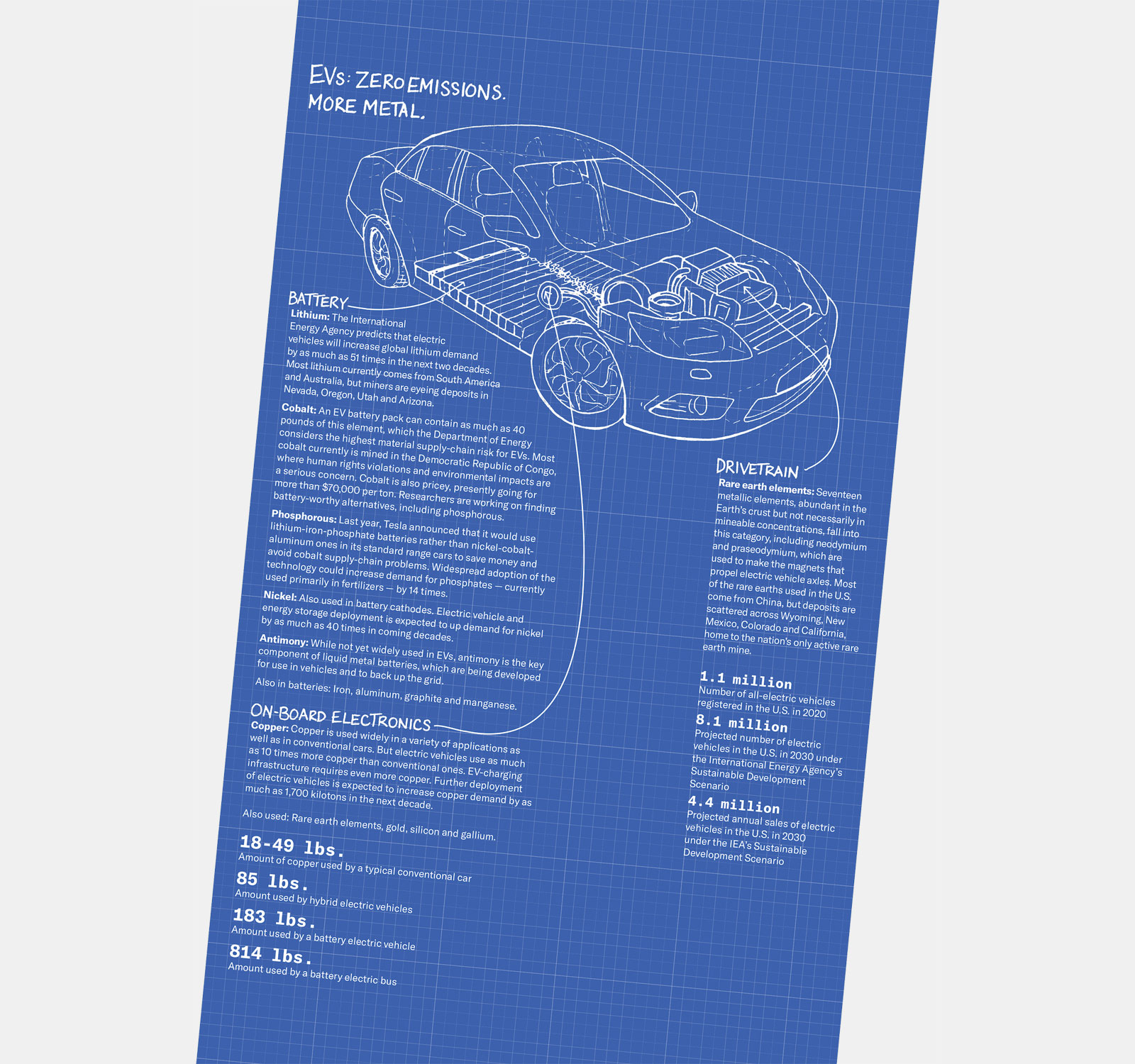

But it will also substantially increase the demand for the so-called energy transition minerals that go into electric vehicles, their batteries and the charging infrastructure — lithium, cobalt, copper, nickel and rare earth elements. Currently, these minerals are largely mined outside of the U.S., in China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia and so on. But with the expected electric vehicle-manufacturing surge on its way, officials from both the auto and mining industries are calling on the federal government to streamline mine permitting in order to bring the supply chain closer to home. The projected demand and the rise in metal prices are breathing new life into Western copper mines and spurring dozens of proposals for new mines from Wyoming to Oregon and Nevada to Arizona.

These minerals, which are also used in wind turbines and solar panels, are sometimes called “green rocks.” But more often than not, their extraction is anything but green. Copper ore is gouged from vast open pits, visible from space as intricate scars on the landscape. All metal mining tends to facilitate a chemical reaction that causes acid mine drainage, which can sully rivers and harm fish and other aquatic life. Cobalt mining can release radioactive and carcinogenic particles, while lithium extraction sucks billions of gallons of water from the ground and the wastewater disposal can contaminate drinking water aquifers.

Efforts are underway to minimize the environmental impacts. At California’s Salton Sea, companies are hoping to tap wastewater from geothermal power production for lithium. Global mining giant Rio Tinto is extracting lithium from waste at its gaping boron mine in California’s Mojave Desert; if the pilot project proves feasible, it could produce lithium without the need for new mining. Innovators are working on non-lithium batteries, and in Nevada one of Tesla’s founders has devoted millions of dollars to develop ways to recycle electric vehicle batteries.

Antimony

Idaho: Perpetua Resources plans to construct an open-pit gold and antimony mine in the defunct Stibnite mining district east of McCall. Historic mining in the area ravaged the landscape and degraded water quality, harming the salmon on which the Nez Perce people depend. Tribal members fear the new mine will bring its own problems. Perpetua says it plans to restore the river and improve water quality.

Cobalt

Salmon-Challis National Forest, Idaho: Australia-based Jervois Global has begun work on the nation’s only active underground cobalt mine just outside the Frank Church Wilderness. The Idaho Conservation League dropped its opposition years ago, after the developers agreed to treat the water in perpetuity and store waste securely in order to protect down-stream water quality.

Lithium

Thacker Pass, Nevada: Proposed by Canada-based Lithium Americas, this open-pit mine would target one of the nation’s largest lithium deposits. The Reno-Sparks Indian Colony and Northern Paiute group Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu (People of Red Mountain) oppose the project, which is on tribal homelands and was the site of two massacres of Indigenous people in the 1800s. The project would use about 1.7 billion gallons of water per year.

Salton Sea, California: Australia-based Controlled Thermal Resources — with backing from General Motors — is drilling deep under the Salton Sea to produce geothermal energy from superheated water. The company plans to tap the wastewater for lithium.

Boron, California: Mining giant Rio Tinto is extracting lithium from waste rock at its huge boron mine in the California desert. It hopes to achieve commercial production levels this year.

Nickel

Oregon: Although there are no active proposals to mine nickel in the West, deposits are scattered across the region. In the 1980s, southern Oregon’s Nickel Mountain Mine was the nation’s only combined nickel mine and smelter, but it shut down due to falling prices.

Copper

Santa Rita Mountains, Arizona: Canada-based Hudbay hopes to capitalize on the projected rise in copper demand with its proposed Rosemont open-pit mine south of Tucson. Hudbay’s website says that “the copper mined at Rosemont will support a cleaner and more interconnected economy.” The proposal has hit regulatory and legal obstacles in recent months, and its fate remains uncertain.

Rare Earth Elements

Mountain Pass, California: The nation’s only operating rare earths mine is in the Clark Mountains near the Nevada border. During the 1980s and ’90s, the mine was plagued by pipeline ruptures, hazardous waste spills and other environmental problems.

Bokan Mountain, Alaska: UCore Rare Metals Alaska is slowly working toward developing a rare earth mine in southeast Alaska on Prince of Wales Island.

Bear Lodge Mountain, Wyoming: After commencing exploratory drilling for rare earth metals at this northeast Wyoming site near Sundance, Rare Element Resources suspended its permit application with the U.S. Forest Service in 2016, citing low metal prices and lack of funding.

White Mesa Mill, Utah: The only operating uranium mill in the U.S., located in southeast Utah, has been retooled to also process rare earth elements.

Recycling

Carson City, Nevada: A study last year found that recycled retired batteries could supply more than half of the global demand for cobalt, lithium, manganese and nickel by 2040, thereby reducing the need for new mines. Nevada-based Redwood Materials, led by Tesla co-founder JB Straubel, says it can recover more than 95% of the critical minerals from recycled batteries. The company recently announced that it will produce recycled copper foils for Panasonic, for use in battery anodes manufactured at the Tesla Gigafactory in Sparks, Nevada.

Sources: U.S. Geological Survey, Ucore Rare Metals Inc., Idaho Mountain Express, Jervois Global, Perpetua Resources, Los Angeles Times, Energy Fuels, S&P Global, Bureau of Land Management, Earthworks, International Energy Agency, Atlantic Council Global Energy Center, Hudbay, Environmental Science & Technology, Pew Research Center.