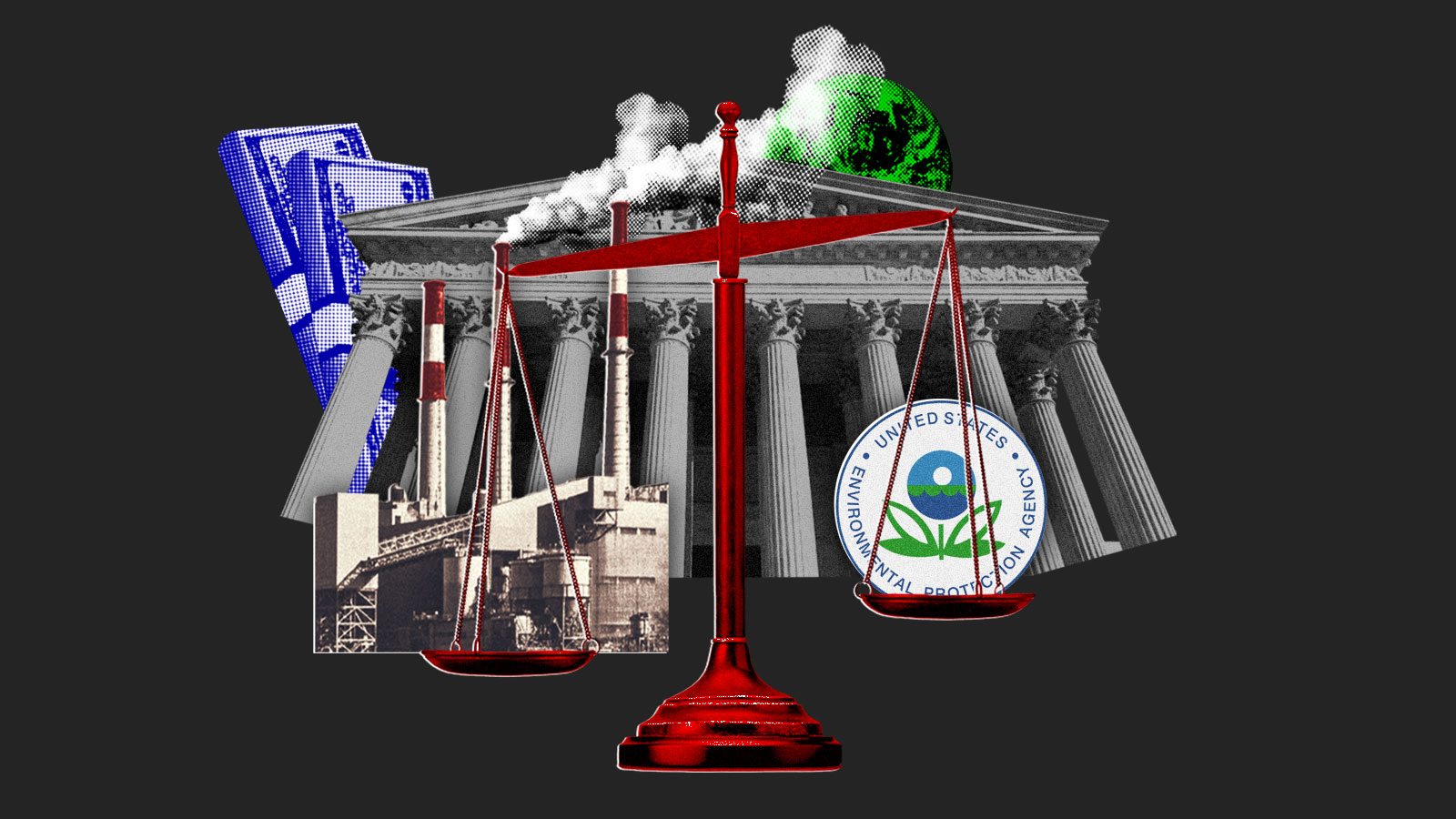

The Supreme Court issued a highly anticipated decision earlier today that constrains the federal government’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. In West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, the six justices who make up the court’s conservative supermajority set a disturbing precedent that could limit federal agencies’ ability to enact regulations. The decision is particularly concerning for the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, as it leads federal efforts to zero out the planet-warming emissions causing storms, drought, and sea-level rise around the world.

The Supreme Court did not arrive at this pivotal moment by chance. For decades, ultra-wealthy conservative donors, libertarian think tanks, and their allies within the Republican Party have orchestrated a campaign to thwart the federal government’s efforts to regulate corporations — including efforts to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, which threaten the profits of the fossil fuel industry. Over the years, they have paid considerable attention to the judiciary, methodically installing conservative judges in anticipation of a case that could kneecap agencies they view as overstepping their authority.

Enter West Virginia v. EPA. The specifics of the case were convoluted, but the arguments at its heart were “a direct shot at the EPA, at their ability to regulate,” said Kert Davies, founder and director of the Climate Investigations Center. “To say they’ve been preparing for this moment for 50 years is not an exaggeration.”

To understand this moment, it’s helpful to consider how we got here.

The 1970s marked the dawn of a new era of concern about the environment. Americans were growing increasingly alarmed by high pollution levels and environmental destruction. There had just been an enormous oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara, the Cuyahoga River had caught fire in Cleveland, and a thick layer of smog regularly smothered cities like Los Angeles. Congress responded by drafting the country’s bedrock environmental laws: the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act — all passed with bipartisan support.

The sudden expansion of federal powers galvanized a new, hard-line libertarian movement helmed by an oil executive named Charles Koch. Koch had inherited a handful of companies from his father in 1967, including a lucrative refinery in Minnesota and a network of pipelines, barges, and trucks that shipped oil across the country. Koch was an ardent believer in capitalism and opposed any government action that went beyond the protection of private property. As he built his business into the second largest privately-owned company in the country, he also began building a network of think tanks and nonprofits to infuse his fringe views into the mainstream.

According to investigative journalist Jane Mayer’s 2016 book Dark Money, which chronicles how conservative billionaires shaped the radical right, Charles Koch and his brother and business partner, David, have personally spent well over $100 million on advancing a libertarian agenda. But even more consequentially, they streamlined the efforts of a small group of like-minded elites towards building what one Koch operative called a “fully integrated network” that has influenced every aspect of the country’s political system.

The Federalist Society, a conservative group that has grown into the most powerful legal organization in the country, became a critical node in that network. In 1982, law students at the University of Chicago and Yale formed the group to promote a deeply conservative legal perspective. The organization received start-up funding from the conservative John M. Olin Foundation, began hosting annual symposia and opening chapters at prestigious law schools, and soon attracted large donations from the Kochs and their peers.

At first, the Federalist Society was an all-volunteer group geared mainly towards law students. In the early 1990s, it hired one of its first paid employees, Leonard Leo, who expanded the organization to include lawyers, judges, and others. From the early 2000s to 2020, Leo served as the group’s executive vice president, overseeing a network of approximately 60,000 members. (All six conservative justices on the Supreme Court are associated with the organization.)

The Kochs’ network of conservative billionaires hasn’t only focused on the judiciary. As they poured money into the Federalist Society, they were also pouring money into deregulation efforts, including many related to climate change. Through the years, Koch- and fossil fuel-backed groups like the Global Climate Coalition, American Energy Alliance, Competitive Enterprise Institute, and American Legislative Exchange Council have lobbied against climate legislation and funded research casting doubt on the science and highlighting the costs of taking action.

But it has long been clear to them that the judiciary would be crucial to eviscerating the government’s ability to regulate corporations and to dismantling the administrative state — the government agencies within the executive branch that create and enforce regulations.

The libertarian groups’ judicial efforts have been focused on usurping a 1984 Supreme Court precedent known as Chevron deference with a relatively new and controversial legal argument known as the major questions doctrine. Chevron deference says that if Congress has not clearly articulated its intention in a law, courts should defer to an agency’s interpretation, as long as that interpretation is reasonable. The idea is that agencies possess expertise that Congress and the courts do not, and that agencies are indirectly accountable to the people through presidential elections.

To the libertarian movement, “Chevron is anathema,” said Lisa Graves, a former senior official for the Department of Justice who is now the executive director of True North Research. “For decades now, they have been seeking ways to reverse this precedent, to minimize this precedent.”

In its stead, conservatives have put forth the major questions doctrine, which says that in “extraordinary” cases that could have “vast” economic and political consequences, the court can ignore an agency’s interpretation of a broad law and prevent it from enacting a regulation unless it receives clearer authority from Congress.

The Supreme Court decided West Virginia v. EPA based on this argument. In doing so, it has undermined agencies’ ability to enact regulations to respond to new threats to the environment or public health if they lack clear guidance from Congress — which has failed to pass any serious climate legislation or any significant new environmental laws since it last amended the Clean Air Act more than 30 years ago.

“That’s radical,” said Patrick Parenteau, an environmental lawyer and professor at Vermont Law School. “That’s going to have massive implications for environmental law across the board.”

While libertarians have long despised administrative agencies’ ability to regulate corporations, it took a while for them to build up enough influence on federal courts to begin whittling it away. In 1991, President George H. W. Bush nominated Justice Clarence Thomas, a Federalist Society member who has repeatedly objected to Chevron deference, to the Supreme Court. About a decade and half later, President George W. Bush nominated Justice John Roberts, a former Federalist Society member, and Harriet Miers, who was a family friend but not a member. The organization mobilized against Miers, and eventually Bush nominated Justice Samuel Alito, who had long been affiliated with the Federalist Society, instead. Roberts wrote the majority opinion in West Virginia v. EPA, and both Thomas and Alito concurred.

Another major conservative victory came in the mid-2010s, when then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell — a Republican from Kentucky and a Koch ally — led a stunningly successful effort to prevent President Barack Obama from appointing federal judges and blocked Merrick Garland’s nomination to the Supreme Court, which he called “one of my proudest moments.” This paved the way for President Donald Trump to install more than 200 federal judges, including three Supreme Court justices.

Guiding Trump was Leo, then the executive vice president of the Federalist Society. In March 2016, Leo met with Trump and Donald McGahn, a member of the Federalist Society who later served as President Trump’s White House counsel. Leo later gave Trump several lists of potential Supreme Court nominees that the Federalist Society would support, including Justice Neil Gorsuch. The Trump campaign released the lists in an effort to court the Republican base, and in a July 2016 campaign rally in Iowa, Trump said: “If you really like Donald Trump, that’s great, but if you don’t, you have to vote for me anyway. You know why? Supreme Court judges.” About a year later, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett appeared on another list of Federalist Society recommendations.

Once Trump was elected, Leo shepherded the nominations of Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett through the Senate. According to Internal Revenue Service filings compiled by True North Research, between 2014 and 2020, Leo and his allies raised more than $580 million for conservative nonprofits that do not have to disclose their donors. The network of nonprofits used much of that to hire conservative media relations firms to place opinion essays, schedule pundits on television shows, send speakers to rallies, and create online videos — all to drum up public support and pressure senators to confirm Trump’s picks.

Now, decades of coordinated efforts by ultra-wealthy conservative donors, libertarian think tanks, and the Republican Party are all coming to a head. While the Supreme Court’s ruling in West Virginia v. EPA could have been even more restrictive, it is still a consequential win for fossil fuel interests and a blow to American efforts to address climate change. To Graves, the Supreme Court’s new direction amounts to revival of the robber baron era, “when courts put their thumb on the scale to strike down laws sought by people in our democracy in favor of corporations,” she said. “You have a Supreme Court that has been captured by special interests.”

Things could soon get even more bleak. Republican state attorneys general are pushing several climate-related cases through the federal court system. The courts could use the major questions doctrine to hobble the government’s ability to restrict tailpipe emissions or to consider the social cost of carbon when reviewing new infrastructure or environmental rules. Parenteau points out that a proposed rule requiring companies to publicly disclose climate risks is now vulnerable, too.

Congress could act to stem the damage. Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat from Massachusetts, has called on her colleagues to expand the court. “I believe we need to get some confidence back in our court, and that means we need more justices on the United States Supreme Court,” she told ABC News. Congress could pass legislation to add more justices, but so far Democratic leadership has not been keen on the idea.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democrat from New York, has argued that the Senate should impeach Gorsuch and Kavanaugh for misleading Congress about their views on Roe v. Wade, another radical ruling handed down by the court last week. “They lied,” she told NBC News. “I believe lying under oath is an impeachable offense.” Removing justices from the court would require a two-thirds majority in the Senate.

In a scathing dissent in West Virginia v. EPA, Justice Elena Kagan wrote: “Whatever else this Court may know about, it does not have a clue about how to address climate change.” In its most recent decision, “the Court appoints itself — instead of Congress or the expert agency — the decision-maker on climate policy.” She concluded, “I cannot think of many things more frightening.”