This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In California’s San Joaquin Valley, the farming town of Corcoran has a multimillion-dollar problem. It is almost impossible to see, yet so vast it takes NASA scientists using satellite technology to fully grasp.

Corcoran is sinking.

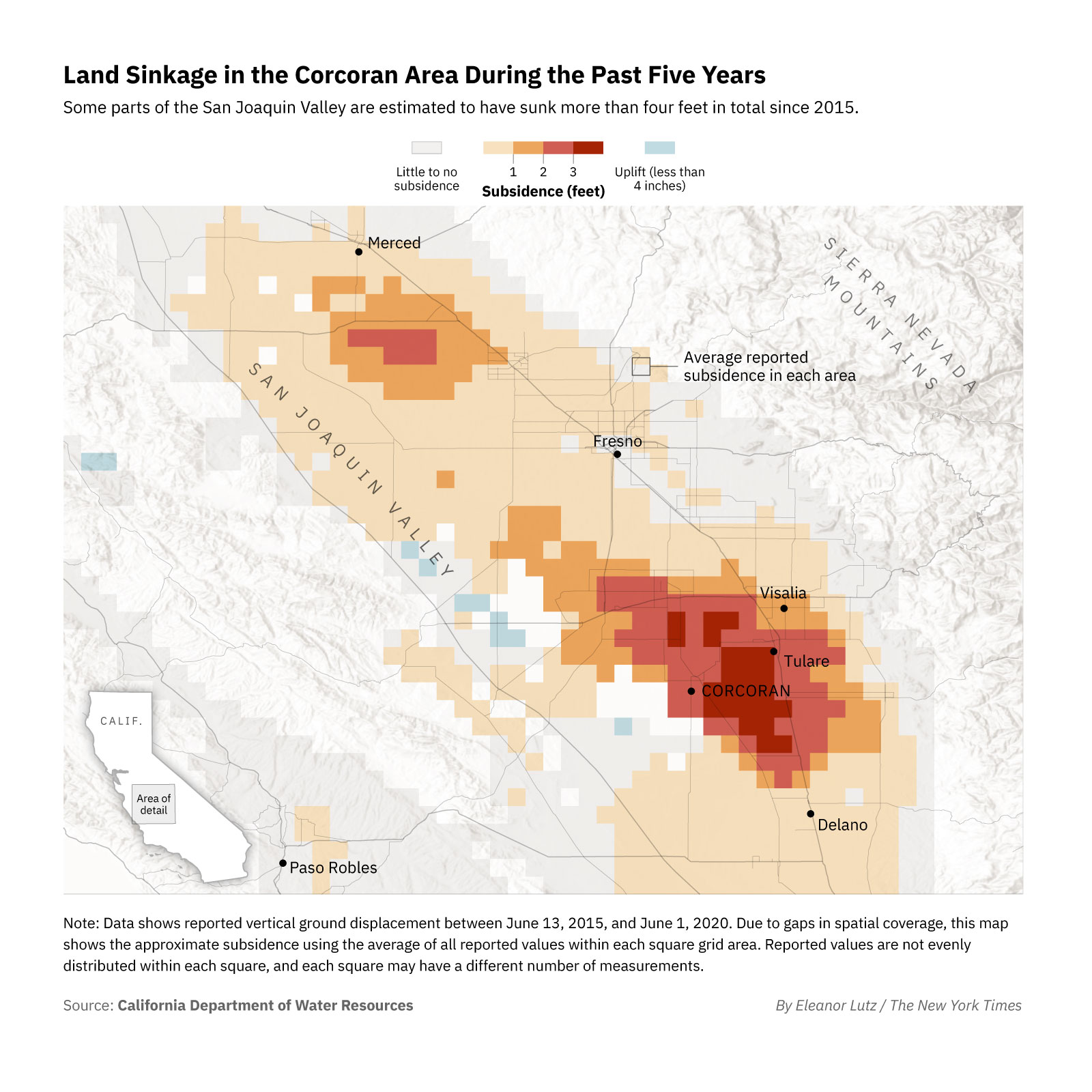

Over the past 14 years, the town has sunk as much as 11.5 feet in some places — enough to swallow the entire first floor of a two-story house and at times making Corcoran one of the fastest-sinking areas in the country, according to experts with the United States Geological Survey.

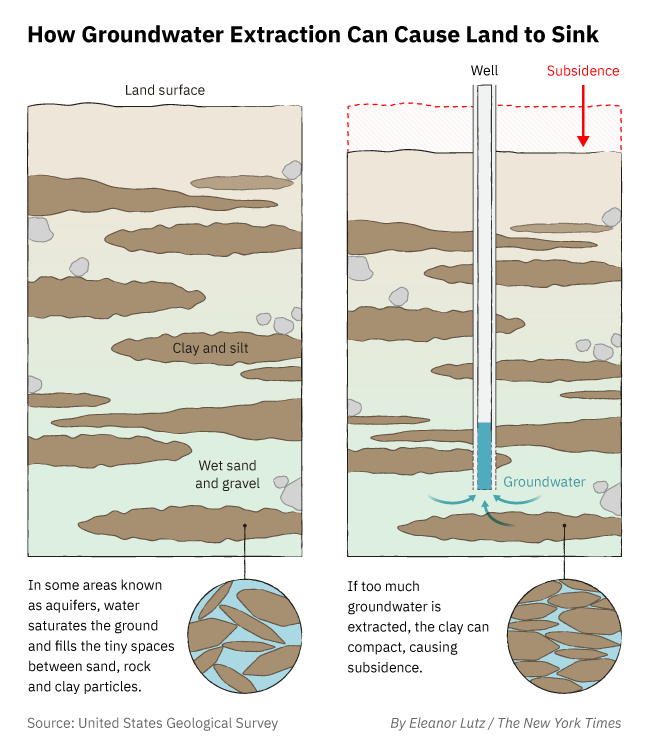

Subsidence is the technical term for the phenomenon — the slow-motion deflation of land that occurs when large amounts of water are withdrawn from deep underground, causing underlying sediments to fall in on themselves.

Each year, Corcoran’s entire 7.47 square miles and its 21,960 residents sink just a little bit, as the soil dips anywhere from a few inches to nearly two feet. No homes, buildings or roads crumble. Subsidence is not so dramatic, but its impact on the town’s topography and residents’ pocketbooks has been significant. And while the most recent satellite data showed that Corcoran has sunk only about four feet in some areas since 2015, a water management agency estimates the city will sink another six to 11 feet over the next 19 years.

Already, the casings of drinking-water wells have been crushed. Flood zones have shifted. The town levee had to be rebuilt at a cost of $10 million — residents’ property tax bills increased roughly $200 a year for three years, a steep price in a place where the median income is $40,000.

The main reason Corcoran has been subsiding is not nature. It’s agriculture.

In Corcoran and other parts of the San Joaquin Valley, the land has gradually but steadily dropped primarily because agricultural companies have for decades pumped underground water to irrigate their crops, according to the USGS California Water Science Center.

When farmers fail to get enough surface water from local rivers or from canals that bring Northern California river water into the San Joaquin Valley, they turn to what is known as groundwater — the water beneath the Earth’s surface that must be pumped out. They have done so for generations.

Corcoran’s situation is not unique. In Texas, the Houston-Galveston area has been sinking since the 1800s. Parts of Arizona, Louisiana and New Jersey have dealt with subsidence problems. The foundations of Mexico City churches have famously tilted, and one 2012 study found that Venice was subsiding at a rate of .07 inches per year.

But how Corcoran came to dip nearly 12 feet in more than a decade is a tale not of land but of water, and the ways in which, in ag-dominated Central California, water is power — so much so that many residents and local leaders downplay the town’s sinkage or ignore it entirely. Few in Corcoran are eager to criticize agricultural companies that provide jobs in a struggling region for helping to cause a little-known geological problem no one can see.

“It’s a risk for us,” said Mary Gonzales-Gomez, a lifelong Corcoran resident and chairwoman of the Kings County Board of Education. “We all know that, but what are we going to do? There’s really nothing that we can do. And I don’t want to move.”

An altered landscape

It is known as the Corcoran Bowl — an area amid the agricultural fields in and near Kings County that stretches at times up to 60 miles. The bowl is the region of deep sinkage in the land, with Corcoran at the center — a sinkhole at a snail’s pace.

Jay Famiglietti helped identify the Corcoran Bowl, although for much of his career he worked for an agency focused more on what is in outer space than what is beneath the ground. He is a former senior scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the research center in Southern California known for aiding planetary exploration missions.

Scientists at the NASA lab have formed an unusual bond with Corcoran, spending years tracking subsidence there and elsewhere in the San Joaquin Valley by using radar and satellite technology.

Famiglietti, now the director of the Global Institute for Water Security at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, began warning of severe sinking in the valley based on satellite imagery as early as 2009. Years later, one of his colleagues at the Jet Propulsion Lab, Cathleen Jones, documented more than 30 inches of sinking west of Corcoran.

“There’s no way around it,” Famiglietti said. “The scale of the bowl that’s been created from the pumping is large and that may be why people don’t perceive it. But a careful analysis would find there is lots of infrastructure potentially at risk.”

Some of that infrastructure has already been damaged.

The Corcoran Irrigation District had to install three lift stations to pump water through ditches. The water used to run on gravity alone, but the sinking created sags in the ditches and caused the water to pool instead of flow through. The district spent $1.2 million over 10 years on lift stations to help push the water along, costs paid for by farmers.

The sinking land crushed the casings of four drinking-water wells used by the city. Insurance paid for two new wells, but city taxes were used to redrill the other two at a cost of $600,000.

And there was the levee that was rebuilt for $10 million in 2017. The levee had sunk from 195 feet when it was built in 1983 to 188 feet in 2017.

“Our residents got hit hard,” said Dustin Fuller, who is the director of the Cross Creek Flood Control District and who led the levee repairs. In addition to the higher property tax bills, some residents bought flood insurance for the first time.

Amec Foster Wheeler Environment and Infrastructure Inc., an engineering company, examined how sinking near Corcoran could affect construction of California’s high-speed rail line, a section of which is being built along the town’s eastern edge. Sinking had altered the topography so much that three flood zones appeared to be merging. The consolidated flood zones could engulf Corcoran and nearby towns in 16 feet of water in a major flood, according to the engineers’ report.

The engineers brought their concerns to state agencies. But no one agency was tracking infrastructure damage from sinking, and no actions were taken in response to their report.

Along Highway 43

The land around Corcoran is tied to agriculture, and so is its economy.

The town is known as the home of a tough state prison that once housed Charles Manson. Corcoran rests alongside Highway 43, roughly 200 miles from both Los Angeles to the south and San Francisco to the north. Nearly 30% of the town’s working-age residents work in the farming industry, and more than 30% of residents live in poverty.

Several large agricultural operations surround Corcoran, including Sandridge Partners, the J.G. Boswell Company, Hansen Ranches, the Vander Eyk Dairies and many others. Collectively, they have hundreds of wells pulling water from beneath the flat, fertile fields around Corcoran.

How much underground water is being pumped by farming companies is nearly impossible to determine. California does not require that information to be disclosed.

Boswell is by far the most prominent agricultural operation in the area. The company started in Corcoran in 1921 and has grown into a $2 billion international enterprise. It has supplied steady work for generations of Kings County families and has been an integral part of the town’s identity, even helping to build the high school football stadium.

Boswell operates more wells in the area than most other ag companies, and far deeper ones. It owns 82 active wells around Corcoran, a majority of which plunge either 1,000 to 1,200 feet deep or 2,000 to 2,500 feet deep. The next largest nearby well owner, Vander Eyk Dairies, has 47 wells, only 10 of which are 1,000 feet deep or deeper.

Boswell’s status as one of the largest and deepest pumpers of groundwater in the Corcoran area — and its decision to sell off portions of its surface water — has raised questions about its role in Corcoran’s subsidence problems.

Some residents and local leaders said they believe that Boswell was leaning more heavily on groundwater for its crops because it had been selling surface water out of the area for substantial profits. In just two sales in 2015 and 2016, one Fresno County water district bought 43,000 acre-feet of Boswell water for $43.6 million.

“If you’re selling off your water, you’ve got no business farming with groundwater,” said Doug Verboon, a Kings County supervisor and farmer.

Others in the area say it is impossible to blame any one water user for Corcoran’s complicated and long-running history of sinkage.

“We’re all pumping,” said Gene Kilgore, the general manager of the Corcoran Irrigation District, which installed the lift stations and serves Boswell and other companies. “Every grower is pumping, every city is pumping, and we all play whatever part there is to subsidence.”

Local Boswell representatives said there was not enough data to know which water user had been pumping what amounts. All of the company’s surface water transfers and exchanges have been approved by state water regulators.

Boswell executives at the company’s headquarters in Pasadena did not respond to emails and calls seeking comment.

The owners of Sandridge Partners and Vander Eyk Dairies declined to comment. An executive with Hansen Ranches did not respond to requests for comment.

The drought’s effects

California has been gripped, yet again, by severe drought. The situation will very likely make Corcoran sink even more.

In the 1960s, California built the State Water Project, a water storage and delivery system, to move water from the north to parched lands in the Central Valley and farther south.

Much of the water comes from the ecologically sensitive Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where concerns over endangered fish have limited how much water can be exported. Amid the current drought, farmers have been told to expect only 5% of their contracted water allotments.

That means farmers may be forced to pump more groundwater to make up for the lack of surface water. That happened during California’s last prolonged drought, from 2012 to 2016, when Central Valley land sank at high rates.

State lawmakers responded by passing a law aimed at stopping water-related land sinkage. The law, known as the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, requires that water basins be brought into balance by 2040 — meaning more water cannot be pumped out than goes into the ground.

Karla Nemeth, the director of the state’s Department of Water Resources, said excessive groundwater pumping and its effect on Corcoran were issues that warranted a closer look.

“The plight of Corcoran is the absolute poster child for legacy unmanaged groundwater pumping that is unacceptable in California and that finally gave rise to (the groundwater law),” Nemeth said.

Ana Facio-Krajcer contributed reporting.

This article was produced by SJV Water, the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ) and The New York Times. The collaboration between SJV Water and CCIJ was led by the Institute for Nonprofit News as part of a project called “Tapped Out: Power, justice and water in the West.”