Want to learn about dinosaurs and elephants and mountain gorillas? Head to your local natural history museum. But if you’re looking to study up on genetically engineered corn, lab rats, or Sea-Monkeys, get thee to the north end of Pittsburgh. There, on a rough little commercial strip with a bike shop, a tattoo parlor, and art galleries, you’ll find the Center for PostNatural History, an outfit run by a local art professor for the express purpose of exploring all the stuff the natural history museums leave out.

Rich Pell, the scruffy proprietor who teaches electronic media classes in the art school at nearby Carnegie Mellon University, sat behind the counter on a recent afternoon wearing a T-shirt from the Smithsonian decorated with a diagram of the tree of life. He explained that his mini-museum focuses on “intentional human changes to the biological world.” Read: dog and chicken breeding, genetically modified fruit flies, and everything in between.

“In a post-natural family tree, the common ancestor always leads back to a person,” he explains — “a breeder, a hobbyist,” or a white-coated lab tech.

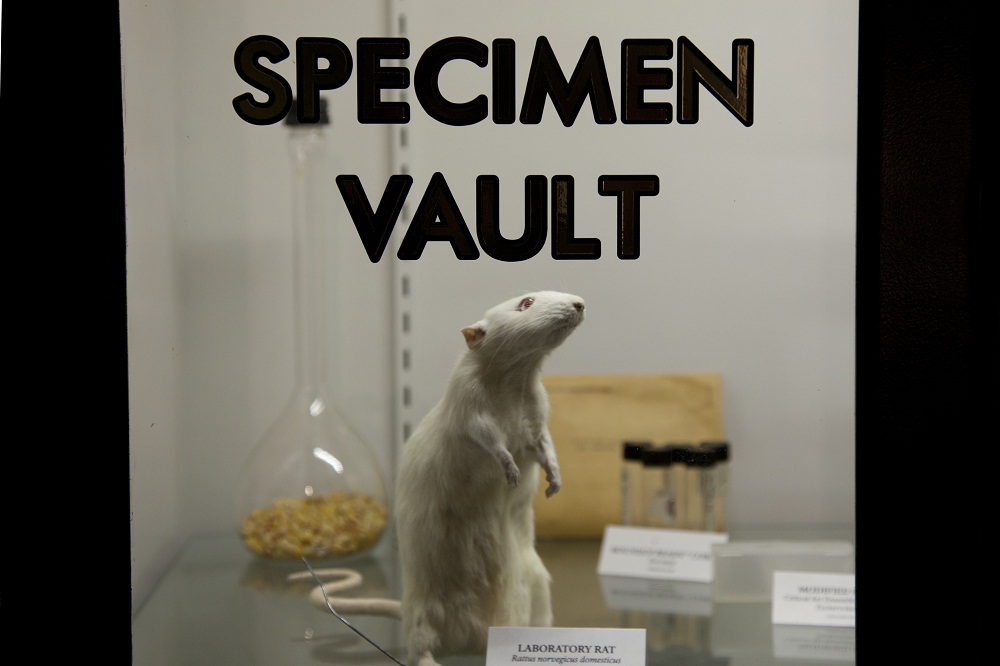

The center itself feels faintly like a dime museum or a freakshow. A specimen case in the front holds a taxidermied lab rat, while behind a black curtain, in the darkened back room, you’ll find specimen jars, petri dishes, and vials containing E. coli bacteria, leaves from a transgenic American chestnut tree, and Sea-Monkeys — those odd little shrimp-like creatures that look nothing like the images on the backs of comic books. One jar, labeled “Forced Castration, Strategies in Genetic Copy Prevention,” contains a pair of cat testicles preserved in ethanol.

But while the place might at first make you wonder if Pell has a peculiar relationship with the paranormal, everything here is quite real. After a little poking around, you realize how freakish ordinary natural history museums are. And how much they gloss over.

In the center’s front window is a collection of young corn plants, sprouting from clods of soil — Monsanto corn, genetically modified to be resistant to the company’s pesticides. Pell didn’t buy the seed from the company — to do that, you have to sign a lengthy legal agreement. (A copy of it is posted on the wall next to the corn. It stretches nearly from the ceiling to the floor.) Instead, he says he sprouted the corn from animal feed and birdseed, then doused it with Roundup. When the pesticide didn’t kill it, he says, “We had a pretty good idea what we had on our hands.”

The main exhibit at the moment, in the cave-like back room, is called “The Cold Coast Archive: Future Artifacts from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.” The centerpiece is a creepy video put together by an international team, including L.A.-based artist Steve Rowell, of a visit to the “doomsday vault” on a desolate Norwegian archipelago. There, scientists are ferreting away seeds deep in the permafrost to preserve food crops in the case of a global environmental catastrophe. The scenes from the vault are set against eerie video of the frozen Arctic landscape and a trip into the bowels of a nearby coal mine.

A small diorama of the vault’s entrance comes with a label explaining that the seeds are kept at 0 degrees F for preservation, but adds, “Seed banks are encouraged to refresh every 6 years to ensure viability. At the entrance to the vault a diesel generator supplies power to an air conditioning unit that maintains internal temperatures.” I feel safer already …

But while the museum is enough to creep you out, it doesn’t hit you over the head with overtly political or moral messages about whether our meddling is good, bad, or otherwise. “Generally, if you want to learn about this stuff, you’ll find that there are advocacy groups that campaign against it, and there are corporations with a vested interest,” Pell says. “We want to let people suffer with themselves, struggle with the issues, and come to their own conclusions.”

Pell says he has seen a steady stream of visitors since the center opened in March, including a goodly number of “activist kids” and high school science teachers, who, he says, “have no place else to get this stuff.” In August, he’ll travel to Amsterdam to open a touring exhibition titled “PostNatural Organisms of the European Union.” “From there, Slovenia in November, and possibly Berlin in the spring,” he says, “and we plan to keep it moving.”

Meantime, he’s happy to talk your ear off about the origin of the common lab rat, the genetic makeup of Sea-Monkeys (yes, they’re brine shrimp, he says, but the story doesn’t end there), and how a drawer full of mouse skeletons in the Smithsonian archives sparked his interest in biological weapons.

It’s not material you’ll find in your typical natural history collection, but by the time Pell is through with you, you’ll wonder why that’s true. In an age when humans have arguably become the dominant force shaping the earth’s natural systems, it pays to take a close look at how we’re deliberately monkeying with the biological world. The fact that much of this stuff comes off as weird science fiction suggests that maybe, just maybe, we’re in over our heads.