Next Monday will mark precisely 10 years since wolves re-appeared in Yellowstone National Park, from where they had been absent since the 1920s. The re-introduction program was a smashing success, far exceeding even optimistic predictions.

Next Monday will mark precisely 10 years since wolves re-appeared in Yellowstone National Park, from where they had been absent since the 1920s. The re-introduction program was a smashing success, far exceeding even optimistic predictions.

On March 21, 1995, federal biologists finally opened the acclimation pens holding 14 gray wolves, sometimes called timber wolves, brought from Alberta. Earlier that year an additional 14 wolves had been set free in central Idaho’s mammoth wilderness. And the following year, 17 more wolves were released into Yellowstone and 20 more into Idaho.

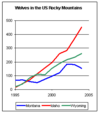

A decade later, Yellowstone’s wolf population has grown more than five-fold and expanded into adjacent areas of Wyoming and Montana. Idaho’s wolf population expanded even more spectacularly–by thirteen-fold–with an estimated 452 animals in the Gem State at last count in 2004. All told, over 850 wolves now roam the US Rocky Mountains. It’s only a matter of time until they begin returning in numbers to Washington and Oregon, where they are now only rare visitors. [Click on the chart at left for state-by-state trends.]

A decade later, Yellowstone’s wolf population has grown more than five-fold and expanded into adjacent areas of Wyoming and Montana. Idaho’s wolf population expanded even more spectacularly–by thirteen-fold–with an estimated 452 animals in the Gem State at last count in 2004. All told, over 850 wolves now roam the US Rocky Mountains. It’s only a matter of time until they begin returning in numbers to Washington and Oregon, where they are now only rare visitors. [Click on the chart at left for state-by-state trends.]

Even better, the return of the native wolf has meant a return to healthier ecosystems. (Perhaps the best study of the effects of wolves on Yellowstone’s ecosystems appeared in the Journal of BioScience in 2003.) Because wolves are a dominant predator, the effects of their presence or absence are felt on many levels–biologists call this effect a “trophic cascade.” For example, wolves preying on beavers can mean more streamside trees–because beavers are fewer in number and fear to linger in the open–which in turn means more shady habitat for trout.

Prior to European contact, wolves ranged across almost all of North America.  But by mid-century ill-advised and relentless programs of hunting, trapping, and poisoning extirpated wolves from their entire American range, with the exception of Alaska and a small remnant population in the wilderness of northern Minnesota and Isle Royale, Michigan. (The wolves in the upper Midwest are actually a different subspecies of Gray Wolf, the Great Plains Wolf, from the Canis lupus of the western US and Canada, which are Rocky Mountain Wolves.)

But by mid-century ill-advised and relentless programs of hunting, trapping, and poisoning extirpated wolves from their entire American range, with the exception of Alaska and a small remnant population in the wilderness of northern Minnesota and Isle Royale, Michigan. (The wolves in the upper Midwest are actually a different subspecies of Gray Wolf, the Great Plains Wolf, from the Canis lupus of the western US and Canada, which are Rocky Mountain Wolves.)

But wolves are tenacious creatures, and by the 1980s a few wolves had crept back over the Canadian border and had begun recolonizing parts of northwestern Montana. By the early 1990s, wolves were reported in remote areas of northern Washington, also Canadian immigrants. Then, in the mid-1990s the US Fish and Wildlife Service began a reintroduction program that catapulted wolf populations to viable sustaining numbers and also into the limelight.

The US National Park Service estimates that over 100,000 visitors to Yellowstone have observed wolves there; and visitors continue to throng the park in the hopes of glimpsing a wild wolf.

But wolves have also bred a fever pitch of controversy–a controversy I don’t fully understand. Certainly, a few ranchers and herders have, I suppose, justifiable concerns about predation of stock, though many of these concerns are addressed by compensation programs.

What’s bizarre, I think, is the amount of attention paid to wolves’ purported lethality to humans. Wolves are not actually dangerous to humans in any meaningful way. Healthy wild wolf attacks on humans are exceedingly rare and are usually the result of human stupidity. In a typical year, 50 Americans die from bee stings, 7 from snakebites, and 25 from dog bites. But in the entire 20th century there’s not been a single documented case of a wolf killing a human in North America, including Canada and Alaska where wolves are relatively numerous. [For more on this subject, and sources for my claims, click here.]

But whether wolves are dangerous seems to fundamentally miss the point. They are a cornerstone to their entire ecosystem–essential for maintaining balance. Their return to the Northwest signifies not only a return to wild-ness, but the beginning of a return to healthy and thriving natural systems. And on the 10th anniversary of their reintroduction, their story is a heartening one because it suggests that we can play a hand in restoring our native ecology.

Next Monday will mark precisely 10 years since wolves re-appeared in Yellowstone National Park, from where they had been absent since the 1920s. The re-introduction program was a smashing success, far exceeding even optimistic predictions.

Next Monday will mark precisely 10 years since wolves re-appeared in Yellowstone National Park, from where they had been absent since the 1920s. The re-introduction program was a smashing success, far exceeding even optimistic predictions.