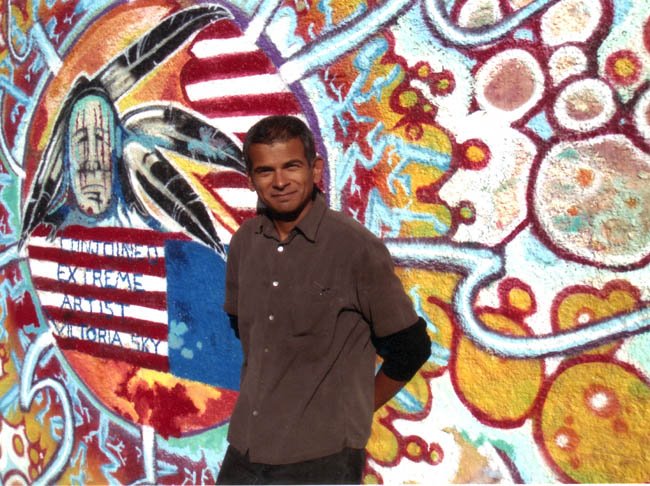

Rod Coronado.“Rod Coronado is not a terrorist,” says Dean Kuipers, author of Operation Bite Back: Rod Coronado’s War to Save American Wilderness and a longtime writer about the world of eco-activism.

Rod Coronado.“Rod Coronado is not a terrorist,” says Dean Kuipers, author of Operation Bite Back: Rod Coronado’s War to Save American Wilderness and a longtime writer about the world of eco-activism.

Back in the 1980s and ’90s, during Rodney Coronado’s radical sabotage campaigns on behalf of animals and the environment, terrorism was generally considered to mean violence against people. Feeling strongly that the loss of any life was wrong and that casualties would harm the movement, Coronado took care to not hurt anyone as he liberated animals and burned down research facilities across the American West. Charged with arson in 1995, Coronado served four years in a medium-security prison and, in August of 2006, was sentenced to eight more months for dismantling a government-owned mountain lion trap.

But over the years, the official definition of terrorism expanded. Through the 1992 Animal Enterprise Protection Act, the 2001 USA PATRIOT Act, and the 2006 Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, the federal government proclaimed that the tactics the radical animal-rights crowd had been using for years were now a form of “terrorism” and could be prosecuted much more harshly.

In 2007, Coronado found himself standing before a judge once more–though not for property destruction, as his days of burning down buildings were long behind him, but for making a speech. While giving a lecture about his past radical actions, Coronado answered an audience question about how to build an incendiary device out of a plastic jug, and for that, Coronado was charged with a felony and ultimately sent to federal prison for a year and a day. Compared to other collared eco-activists who have been threatened with sentences of up to 20 years under the stricter federal laws, perhaps he got off easy.

Kuipers has been following Coronado’s flame-broiled tale of radical action for 17 years and tells the whole story in Operation Bite Back. Kuipers makes it clear that he does not advocate arson or property destruction, but challenges us to consider whether it’s reasonable to apply the label of terrorist to someone who releases animals from a lab.

——

Q. How has the shifting definition of “terrorism” changed the environmental movement since the 1980s?

A. I think a lot of the old-timers, the “rednecks for wilderness”–it’s sort of where Earth First! began, and Sea Shepherd too in a way–might pin a little bit of that expansion of the term “terrorism” on the late ’80s-’90s anarchists who came into the scene. Guys like Rod Coronado. They changed things a lot because the original eco-radical[s], like Greenpeace, were sort of mainstream conservation guys — they called themselves conservationists. Mostly they were white men who had parties out in the woods and ate steaks and drank whiskey. They were kind of red-blooded Americans, like the heroes of The Monkey Wrench Gang.

And then this whole new contingent, right around 1990, started coming in that was much more about anarchism and identity politics. “What do I believe, and how does that separate me from the rest of the world?” People got into listing their issues. “I not only don’t eat animals, but also I am transgendered and I have these piercings that are very important to me.” Those kind of issues just drove the old-timers insane, because all of those things started being in the radical journals: “What are we going to do about the homophobia in our movement?” Those are all important discussions, but they didn’t have anything to do with saving whales or species problems. That was very disconcerting to the old school of the movement. A lot of them kind of left the movement, because they didn’t think that was as important as saving a chunk of wilderness or preserving a specific species.

And then this whole new contingent, right around 1990, started coming in that was much more about anarchism and identity politics. “What do I believe, and how does that separate me from the rest of the world?” People got into listing their issues. “I not only don’t eat animals, but also I am transgendered and I have these piercings that are very important to me.” Those kind of issues just drove the old-timers insane, because all of those things started being in the radical journals: “What are we going to do about the homophobia in our movement?” Those are all important discussions, but they didn’t have anything to do with saving whales or species problems. That was very disconcerting to the old school of the movement. A lot of them kind of left the movement, because they didn’t think that was as important as saving a chunk of wilderness or preserving a specific species.

The use of the word terrorism was always around, even in the ’60s, early ’70s — but it was always rhetorical. I think it was Ron Arnold who actually coined the term in 1982: “eco-terrorist.” But it was rhetorical at that time because eco-terrorism didn’t exist. Unless you killed somebody, you weren’t a terrorist. And they hadn’t killed anybody, so there wasn’t any eco-terrorism.

Changing [terrorism] laws [to encompass environmental activism] really came about because guys like Rod Coronado went further, started using arson. The threat of more violence was sort of there in that movement and I don’t think that went over very well with a lot of the conservation movement, and they kind of split off in a lot of ways. So I think that the Animal Liberation Front and Earth Liberation Front and people who modeled themselves after them have found themselves very isolated from the rest of the movement.

Q. Where do you see the eco-movement going from here?

A. I think that the mainstream approach is totally taking over right now, and they’re being successful. Kind of all they had to do is wait out George Bush. I think they have a very sympathetic ear right now. All of the big groups — NRDC, the Sierra Club — are very effective right now. They have sympathetic ears in Congress; people like Henry Waxman [chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and cosponsor of the House climate bill] kind of took the key positions that they needed them to take. The deck is loaded now for a lot of stuff to happen.

However, I think that the radical parts of the movement arise because of threat. The global warming question will continue to get bigger, and species extinction and various types of animal abuse, for lack of a better word, are not going to get better. So I think that that kind of action will rise. I don’t see that the terrorism laws have ever really stopped it because people — young people in particular — just assume they won’t get caught. And they’re right. They’ve hardly caught any of those people through the years, [even though there have] been over 1,200 actions and like a billion dollars worth of damage.

I think that the radicalism will rise if the mainstream movement fails to get anything done. I think that’s why there’s always a radical element to any movement. They’re there to step it up and push everybody to a more aggressive position. If they pass some real bullshit legislation about global warming that’s basically full of loopholes and everybody can drive a Hummer, the radicalism will step up.

Q. How do people respond when you talk about your work?

A. It depends on who it is. There’s such a huge community of people who believe in more radical action — called direct action — in solving environmental and animal rights problems that there’s a lot of sympathy. But there [are] a lot of people for whom Rodney Coronado is not radical at all and would like to see it go far beyond that.

But that’s not the mainstream, and for the most part, mainstream America doesn’t really want to get involved in this. They still eat meat and they don’t really want to think about factory farms or where their mink coat comes from. Consciousness has definitely gone way, way up, but still it’s a huge jump from being conscious about where your food comes from or where your coat comes from to being somebody who knows people who actually go out and do stuff about it, [whether] it’s just legislation [or] actually trying to close a place down physically. That’s kind of shocking.

I’m sure my family in Michigan would be a little bit appalled: “Another book from Dean that we can’t read!”

Q. Have you faced conflicts within the mainstream media because there are stereotypes about environmental activists?

A. I haven’t encountered that many serious challenges. You have to dial things back. You have to position them in such a way that the publication feels comfortable that you haven’t just completely denied one half of the story from getting its say. Even when we know things are just absolutely for sure — something like a cancer cluster of people from asbestos — you’ve still got to call for a comment from the asbestos department where they say, “No, it’s not us.” But I do that, so there haven’t been too many stories I’ve brought to people where they’ve just said, “No, that’s too radical for us.”

Even in my book, I don’t write about Rod Coronado saying that arson is awesome. Arson is not awesome. Arson sucks. It’s a thing that people should not do, but it’s a tool that he used and I present it pretty matter of fact. I’m sure I will be accused of being an apologist for arson, but that’s not my purpose. But if I did write a book about that, I don’t think it would be as good, because suddenly there’s no reason for any of the farmers to talk to me, the FBI, the police. All those guys have amazing and cool facts that I don’t know, and I want all that stuff. As long as we do that, I think the story gets better and people are more open to reading it. I lose less of the audience. You can make more of a difference.

Q. What originally drew you to writing about eco-radicalism?

A. [The actions] happen in great locations. I grew up in the woods in Michigan with a big hunting and fishing family. I was living in New York City when I first started doing this stuff and really sweating it, and having a hard time getting myself out to the Catskills on the weekends to see some trees.

But there are whole protests that last for months happening in redwood groves in Northern California, and people trying to stop roads from being built into central Idaho, which is like God’s Country. It’s just amazing there — huge contiguous pieces of roadless wilderness with wolves and moose. Those are the kind of places I like to be in. And on a boat with the Sea Shepherds out in the eastern tropical Pacific to Cocos Island or something — it’s fantastic. I’m not only working on a story, but I’m in the places I would like to see preserved.

Q. Does it water down our legitimate concerns about terrorism to have environmental and animal-rights activists looped into it?

A. Sure. I think it’s an insult to the intelligence of the average American, that we can’t tell the difference. But of course we can tell the difference! Osama bin Laden goes on the TV on one of his Al Jazeera tapes and says, “We will make the infidels pay,” and that’s about killing people. The Militant Vegan League — which is something I’m just making up — sends out their communiqué saying you have to stop hurting bunnies and you have to stop factory farming where you keep chickens in little cages. It’s just a completely unrelated issue in every way — strategically, philosophically, tactically, in every way. Terrorism is such a strong word that it just allows the same kind of law enforcement tactics to be used to suppress it.

Q. What is the No. 1 message you want to stick with people after reading your book?

A. What we were just talking about. I picked out a particular person–Rod Coronado–to help me tell the story because I want it to be obvious by the time you get to the end that Rod Coronado is not a terrorist. He’s done lamentable things, he’s burned things and attacked businesses and been very aggressive. But he’s never attacked any people. He’s an intelligent and respectful person who did things on principle and believed that he was executing the height of nonviolent direct action.

There’s a difference between bursting into the Holocaust museum with a gun with the intention of “I’m going to kill a bunch of people to make a statement,” and going into someplace late at night and burning their fence and making sure that no people are hurt because you want to make a statement.

We need to take some action to preserve the difference, for all kinds of reasons. So that people don’t rot in jail who don’t need to for long periods of time. So that we, as a country, are not spiritually affected by this — I think that there’s a price to pay when your country endorses things like torture, and calling people terrorists who are not terrorists plays into that. You’re falsely accusing certain sectors of the public of doing something they’re not doing.

I also think that it’s not that good for us environmentally, that we shouldn’t be able to demonize people who are trying to get a message across that many people would recognize as positive.

Catch Dean Kuipers on his book tour or follow him on his blog. You can also see him on BookTV Sunday, July 25.