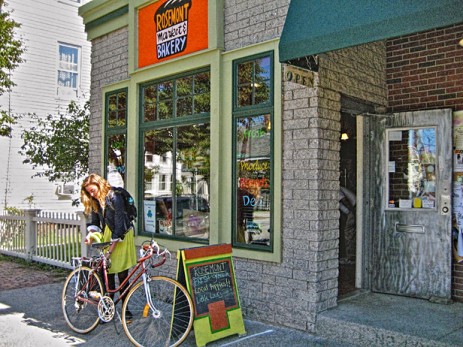

Our new neighborhood fresh food market.What I find most striking about my mother-in-law’s memories of the neighborhood where I live, and where she spent her childhood in the 1940s, is how many businesses our little residential section of town once boasted. Back then, there was a grocery store, hardware store, barber shop, two drugstores, a tailor, and several corner stores.

Our new neighborhood fresh food market.What I find most striking about my mother-in-law’s memories of the neighborhood where I live, and where she spent her childhood in the 1940s, is how many businesses our little residential section of town once boasted. Back then, there was a grocery store, hardware store, barber shop, two drugstores, a tailor, and several corner stores.

Those businesses all disappeared in the following decades, as the streetcar lines were dismantled, families acquired cars, and shopping migrated out to supermarkets and, later, malls and big-box stores. At the low point, my neighborhood hosted little more than a lone convenience store, great for snacks and beer, but not much else.

Recently that began to change: first a restaurant opened and then a tea shop. And then, in what many of my neighbors greeted as nothing short of a gift from heaven, a small fresh food market opened. Stop by at 6 in the evening and you’ll find a row of bicycles out front and the store’s narrow aisles packed with people pondering their dinner options.

This little store is one of hundreds of new neighborhood businesses that have opened in the last few years in what might be both the beginnings of a revival of small retail and one of the more important strategies we have for countering global warming.

So far, the public debate about cars and climate change has been dominated by fuel economy. But driving has been growing at such a rapid pace — total miles driven in the U.S. rose 60 percent between 1987 and 2007 — that even a big advance in fuel economy is likely to be wiped out by ever more miles on the road.

According to calculations by Steve Winkelman of the Center for Clean Air Policy, even if we achieve a major improvement in fuel economy (new vehicles averaging 55 mpg), cut the carbon content of fuel by 15 percent, and slow the growth rate for driving significantly, by 2030 greenhouse-gas emissions from transportation will be only slightly below 1990 levels.

That’s nowhere near the 60-80 percent reductions we need by mid-century to avoid the worst effects of global warming. Perhaps electric cars will come online fast enough to close the gap, but we would do well to hedge our bets by also finding ways to make daily life not require quite so much driving.

This is where local stores come in. Academics who study travel behavior say that the presence of neighborhood businesses is a major factor in how much we drive. Dozens of studies have found that people who live near small stores walk more for errands and, when they do drive, their trips are shorter. And that’s not all: a more surprising research finding is that small retailers influence how likely people are to take public transit to work.

One study, led by Susan Handy, an expert on travel behavior at the University of California-Davis, examined eight neighborhoods and found that how often people walked for errands closely tracked both the number and proximity of stores. In the neighborhood with the most businesses, where homes were on average only one-fifth of a mile from the nearest store, 87 percent of residents regularly ran errands on foot, averaging 6.3 shopping trips on foot per month. In the neighborhood where the nearest store was an average of three-fifths of a mile away, only one-third of residents reported walking to a store in the previous month and averaged only 1.4 errands on foot per month.

Another study by Handy found that residents of an Austin, Texas, neighborhood that has numerous small stores within a half-mile radius made 20 percent of their food shopping trips on foot and logged 42 percent fewer miles driving to supermarkets than residents of two Austin suburbs that lacked neighborhood stores.

The potential impact of these findings is quite significant. Shopping accounts for 1 in 5 trips we take and has been the fastest growing category of driving by far. In the late 1970s, the average household drove 1,200 miles a year for shopping. That figure has skyrocketed to about 3,600 miles today. What changed? Stores got a lot bigger. Between 1982 and 2002, more than 100,000 small retailers disappeared. The big-box stores that replaced them were many times larger, far fewer in number, and thus served larger geographic areas.

Reversing the super-sizing of retail and bringing back neighborhood stores would not only cut the miles we chalk up running errands. It could also prompt more public transit use. A study of 3,200 households in King County, Wash. (the Seattle area), found that the choice to commute by transit was strongly influenced by the number of retail stores near home and work (probably because people could opt for the bus and still run a few errands on the way home). Overall, the study found, residents of the most walkable neighborhoods logged 26 percent fewer miles than those in the most auto-oriented.

Critics have argued that these studies merely reveal people’s preferences: those who like to walk choose neighborhoods where they can walk. But recent research has controlled for this “self-selection” bias — by, for example, tracking people as they relocate — and found that preferences matter but so too does the built environment. Those who favor driving walk more and drive less if they move to areas where there are places to walk to.

But the self-selection debate may be moot anyway. Demand for mixed-use neighborhoods is growing rapidly and may have already outstripped supply. In a new report, CEOs for Cities analyzed sales data for 90,000 houses and found that, in 13 of 15 markets, those in neighborhoods with higher Walk Scores have held value better than those in areas lacking destinations within walking distance.

These shifting preferences have the potential to remake the American landscape, but only if our public-policy priorities change too. Right now, everything from federal transportation spending to state economic-development incentives and local land-use policies heavily favor driving over transit, big-box stores over neighborhood businesses, and sprawl over infill.

Reversing these policies will be no small task. But bringing small businesses into the debate could improve the odds in two key ways. For one, having more stores within walking distance is the tangible, enticing upside of planning concepts that otherwise seem abstract, if not downright unappealing, like “density” and “street connectivity.”

Engaging independent business owners could also provide a powerful counterweight to big business groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which is now waging an all-out offensive to ensure that, when Congress undertakes its once-every-six-years renewal of federal transportation spending, the new program heavily favors highway expansion.

On the other side of the debate is Transportation for America, a coalition of groups favoring more investment in transit and smarter land-use planning. The coalition recently gained a new member: the American Independent Business Alliance, an eight-year-old national network that represents about 15,000 independent businesses (and on whose board I serve).

“It’s no coincidence that you rarely find local retailers in the big shopping centers that develop along highways,” explained the group’s outreach director, Jeff Milchen. “What we hear from many independent business owners is they compete more successfully integrated into neighborhoods, where their personal service and small scale are assets.”