During the widely-watched Supreme Court re-argument Wednesday morning of Citizens United v. Federal Election Coalition – a case that challenges the constitutionality of over a century of campaign finance laws restricting corporate spending during elections – the Justices’ varying opinions on corporations were on full display. While some, notably Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, expressed concern at the enormous influence of “mega-corporations” in politics, others seemed far more sympathetic to corporations’ motives.

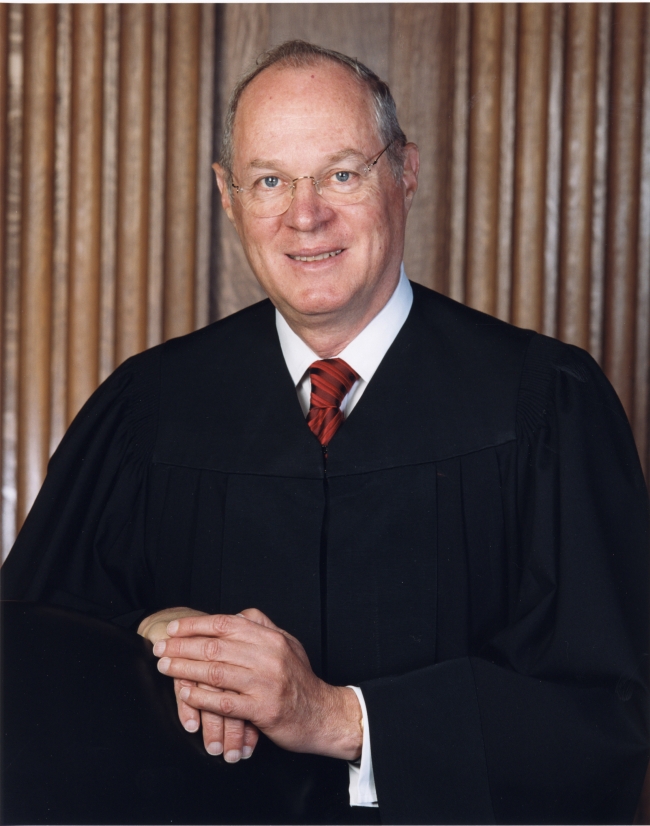

During an exchange with Solicitor General Elena Kagan (arguing on behalf of the FEC) over whether corporations should be permitted to influence policymaking, Justice Anthony Kennedy said:

Corporations have lots of knowledge about environment, transportation issues, and you are silencing them during the election. (52:7)

Later in the argument, Kennedy questioned whether it is appropriate to restrict …

… the phenomenon of television ads, where we get information about scientific discovery and environment and transportation issues from corporations, who after all have patents because they know something. (73:5)

(Transcript here.)

Justice Kennedy’s comments warrant some analysis, especially given their implications for the climate debate. (Most experts came away from Wednesday’s argument expecting Justice Kennedy to join his conservative colleagues in striking down campaign finance restrictions.) Kennedy suggests that corporations have a right (a constitutional right, no less) to share their abundant knowledge about scientific discovery and the environment during elections. This assertion, however, is based on two horribly flawed premises:

-

Corporations’ “goal” in spending money during elections is to share their knowledge.

-

Corporations have no way of sharing this knowledge other than spending money to influence elections.

The first is naïve. As General Kagan herself noted during argument (countering an assertion by Chief Justice Roberts that corporations have “diverse interests” in elections), corporations have “a fiduciary obligation to their shareholders to increase value. That’s their single purpose, their goal.” In other words, the reason a corporation tries to influence elections is to increase its profit, not to educate the masses.

The second is even more suspect. Does anyone believe that energy companies like Exxon Mobil face any difficulty sharing their “knowledge” and opinions regarding environmental policy? Here are a few of the many, many ways corporations like Exxon communicate with us:

-

Prolific, expensive, carefully-targeted advertising. This, of course, happens on a scale much greater than individuals, small non-profits, or campaigns can hope to match. ExxonMobil, for instance, for years ran a quarter-page “Op-Ad” on the editorial pages of the The New York Times and has recently been putting an ad on the front page of the Times about auto emissions.

-

Influencing judges. ExxonMobil, has funded fancy junkets to “educate” federal judges about climate change. Interestingly, Justice Kennedy himself agreed in an opinion (Caperton v. Massey Coal) handed down last Term that expenditures by CEO Don Blankenship of Massey Energy to influence a West Virginia state judicial election resulted in a serious conflict of interest when Massey came before the judge as a litigant. Implicit is the acknowledgement that corporate campaign expenditures can create, or appear to create, undue influence on elected officials.

-

Influencing “science.” Corporations, especially energy companies like Exxon, fund and influence climate “research” and “experts” to cast doubt on climate change. Turning again to the Supreme Court’s own record on this: in Exxon v. Baker – the 2008 case dramatically reducing the punitive damages awarded to the victims of the Exxon Valdez oil spill – Justice Souter (finding in Exxon’s favor!) noted in a footnote that while the Court was aware of a “body of literature” supporting Exxon’s claims regarding the efficacy of punitive damages, “because this research is funded by in part by Exxon, we decline to rely on it.” (pp.27-28)

The list goes on.

In short, corporations have a huge, some would say detrimental, impact on environmental policy. Spending on elections may be the sole area where Congress and the courts have repeatedly determined it necessary to keep corporate influence out — and this restriction ought to be kept in place.

Let’s hope in his deliberation of Citizens United, Justice Kennedy realizes that while corporations may “know something” about the environment, that hardly justifies allowing them to spend unlimited money to influence the outcome of elections. If he doesn’t, we could find ourselves with elected officials even more beholden to ExxonMobil.