If we can’t yet require companies to reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping pollutants, can we shame them into doing it?

If we can’t yet require companies to reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping pollutants, can we shame them into doing it?

The Obama administration and Democratic leaders in Congress have not so far succeeded in forcing big polluters to cut greenhouse-gas emissions. But the U.S. EPA is about to force them to report their greenhouse-gas emissions.

Big whoop, you say? Well, actually, it might be.

The new Greenhouse Gas Reporting Rule, which took effect last month, requires industrial facilities that release 25,000 metric tons of CO2-equivalent a year to measure and report their emissions. (For comparison, that’s roughly what 2,200 average U.S. households emit annually.) Initially the rule will affect about 1,200 sites — including factories that produce chemicals, cement, iron, and steel. A facility can stop reporting if it emits less than 25,000 tons for five years or less than 15,000 tons for three years.

The emissions data collected will be made public starting in March 2011. Affected companies will find themselves in a searchable database — and maybe in the headlines too. The data could well become fodder for “the biggest polluters in Area X” local and national stories.

Climate advocates hope the rule will inspire companies to cut their emissions voluntarily. “Some companies may have a light bulb turn on when they come face to face with their own emissions,” said David Doniger, climate policy director at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Even if companies aren’t interested in doing the right thing for its own sake, they might act to avoid bad PR. And the added attention on emissions could raise public support for regulations with teeth.

“When the data becomes public in 2011, it starts a critically important conversation in America about who the big emitters or greenhouse gases are, where they are located, and what commonsense steps they are taking to address their contribution to the climate crisis,” said Vickie Patton, an air and climate specialist at Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and a former EPA attorney.

There is historical precedent for this. In 1985, in the midst of President Reagan’s assault on federal regulation, merely preserving clean-air and clean-water laws seemed to be the best hope, never mind expanding them. In the wake of the Bhopal, India, chemical disaster in 1984, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) and others tried to close gaps in federal protection from airborne toxic pollution. Their legislation was pared down to a mere requirement that firms measure and report their emissions—the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI). Chemical industry groups fiercely opposed even this, but it became law.

Waxman recounts what happened next in his book The Waxman Report: How Congress Really Works:

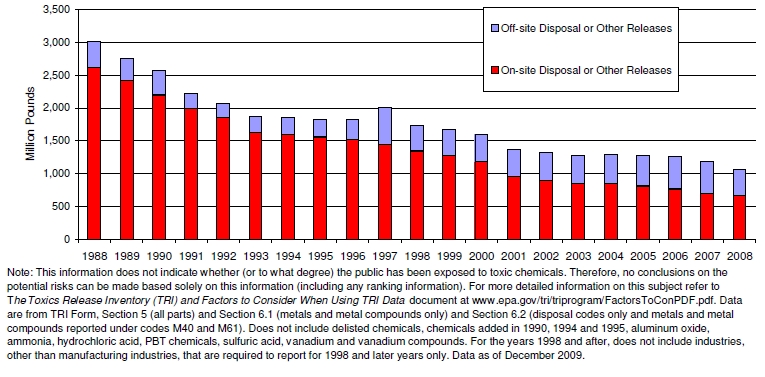

The National Toxics Release Inventory could not, of course, reduce air pollution. But the invaluable information it provided became the basis for legislation that could. The first report appeared in March 1989 and immediately become front-page news across the country. It showed that a staggering 2.7 billion pounds of toxic air pollution was released into the air in 1987.

The media coverage and public outrage spurred by the Toxics Release Inventory eventually pushed Congress to regulate 184 new toxics in the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. The inventory is still up and running, with a community explorer searchable by ZIP code. The law has also corresponded with a steady decline in toxic emissions:

Disposal of toxics measured measured by the Toxic Release Inventory, 1988-2008

Source: EPA TRI 2008 analysis [PDF]EPA

Source: EPA TRI 2008 analysis [PDF]EPA

Before you get your hopes up …

There is a key difference, though, between the new rule and the toxics rule. The TRI told citizens which companies were causing measurable harm to their communities. But greenhouse gases aren’t toxic and don’t have direct regional effects, so there’s less reason for locals to care about emissions from nearby factories. Gases released in Denver and Beijing have the same effect in Denver.

This distinction may not matter in the minds of citizens, who like their local companies to be good corporate citizens across the board. And climate change will carry toll on public health, even though the effects are less immediate: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expects it will promote the spread of infectious diseases like malaria, worsen the effects of asthma, make heat-related illnesses more common, cause extreme-weather disasters, and threaten food security.

The impact of the new rule could also be limited because not all of the data it collects will be new. Large electric utilities have been reporting their greenhouse-gas emissions under the EPA’s acid rain program since 1995, and this hasn’t led to significant reductions. “We have hour-by-hour emissions data for every big power plant,” NRDC’s Doniger said. “It’s very good data and it’s very important for understanding how to build a climate control program, but it hasn’t inspired a lot of them to cut their emissions back.”

The new rule also has some obvious gaps — like letting several key industry sectors off the hook. About 40 agriculture sites emit more than 25,000 tons of CO2 equivalent, but they are excluded from the rule by a directive from Congress. The EPA has not finished its reporting requirement for coal, oil, and natural gas extraction either, which has led to a lawsuit from EDF and Earthjustice. And the agency must resolve legal challenges from as many as eight business groups opposing the rule, though an EPA official familiar with the program said the potential lawsuits were unlikely to stop the rule.

The new rule’s greatest value is probably the information it will give to policymakers designing climate action plans. “Thoughtful, well-designed public policy requires rigorous data,” said Patton. “This greenhouse-gas emissions data is the foundation.”

The new rule took effect just before another big step in corporate transparency on climate issues—a Securities and Exchange Commission ruling that companies “must consider the effects of global warming and efforts to curb climate change when disclosing business risks to investors.” This too could lead to more public understanding of just how disruptive climate change could be to U.S. businesses, and to more pressure for businesses to do their part to avert it.

In the big picture, of course, the planet continues heading toward tipping points beyond which scientists fear it will be too late to stop climate change. Voluntary cuts from businesses are no longer enough, and even if the new information shines new attention on large polluters, there’s no reason to wait for that.

“Frankly, I hope we have [climate] legislation before those public reports come out,” Doniger said.