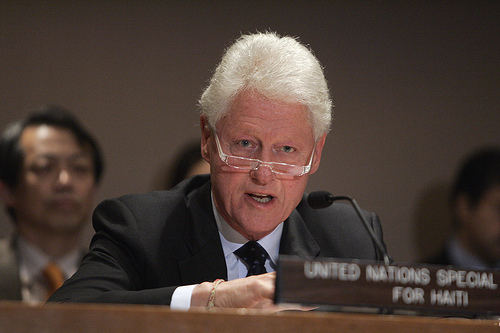

Bill Clinton speaks at the UN. What lessons has he learned about agriculture? Photo: United Nations Development ProgrammeWhat have Haiti’s recent calamities taught U.S. decision makers about foreign policy with regard to agriculture?

Bill Clinton speaks at the UN. What lessons has he learned about agriculture? Photo: United Nations Development ProgrammeWhat have Haiti’s recent calamities taught U.S. decision makers about foreign policy with regard to agriculture?

Haiti imports nearly half of the food consumed there–and 80 percent of its rice, the national staple. In the past two years, the country has undergone two major shocks: the global spike in food commodity prices in 2008, and this year’s devastating earthquake. In both cases, the dearth of domestic food production, combined with the complete absence of rice reserves, translated to widespread hunger and misery.

For a nation to rely on global commodity markets for its sustenance is to depend on forces completely out of its citizens’ control. Actions in other countries–say, the U.S. government’s decision to ramp up ethanol production in 2007–can price millions out of food markets. Natural disasters can quickly morph into monstrous human tragedies. In Haiti, a people with a long history of toughness and resourcefulness become frightfully vulnerable.

For 30 years now, U.S. policy makers and the so-called “Washington Consensus” institutions–the IMF and the World Bank–have goaded “developing nations” to forget about food security and instead focus on leveraging their “comparative advantages” to earn hard currency through foreign trade. Typically, those advantages end up being large pools of cheap labor and natural resources. As for feeding the domestic population, the global commodity market would take care of that.

The 2008 food crisis, which pushed hundreds of millions from mere poverty to flat-out hunger, exposed the absurdity of that policy. No country threw its farmers to the wolves more decisively than Haiti, which just a generation ago grew most of its own food and was a net rice exporter. And now their are signs that U.S, policy makers are rethinking the old advice, as Tom Laskawy recently reported here.

Bill Clinton is a paid-up member of the foreign policy establishment: former President, current UN envoy to Haiti, husband of the Secretary of State. Speaking of his decision in the 1990s to push Haiti to accept cheap, subsidized U.S. rice imports at the expense of its own farmers, Clinton told he Senate Foreign Relations Committee that… (transcription of the Clinton quotes pulled from the Democracy Now website.)

Since 1981, the United States has followed a policy, until the last year or so when we started rethinking it, that we rich countries that produce a lot of food should sell it to poor countries and relieve them of the burden of producing their own food, so, thank goodness, they can leap directly into the industrial era. It has not worked. It may have been good for some of my farmers in Arkansas, but it has not worked. It was a mistake. It was a mistake that I was a party to. I am not pointing the finger at anybody. I did that. I have to live every day with the consequences of the lost capacity to produce a rice crop in Haiti to feed those people, because of what I did. Nobody else.

That’s a remarkable statement. He later referred to the destruction of Haiti’s rice farmers as a “devil’s bargain. He added this:

And it’s [the old ag policy] failed everywhere it’s been tried. And you just can’t take the food chain out of production. And it also undermines a lot of the culture, the fabric of life, the sense of self-determination.

But then in later remarks, Clinton called into questions the lessons he had actually learned. Speaking of Haiti specifically, he said this:

And we–that’s a lot of what we’re doing now. We’re thinking about how can we get the coffee production up, how can we get other kinds of-the mango production up–we had an announcement on that yesterday–the avocados, lots of other things.

By mentioning coffee, mangoes, and avocados, Clinton seems to be indicating an emphasis on export crops. To understand why this is deeply problematic, you have to fully understand the old policies. The idea went like this. Well-capitalized farmers in the globe’s temperate zones — essentially, the U.S., Europe, Brazil, and Argentina — would produce high-volume staple crops like corn, soy, and wheat. In the tropical and sub-tropical zones, farmers would forget staple crops and focus on “high-value” (and labor-intensive) fruit, vegetables, and flowers for the northern countries, where consumers can pay high prices for them. Comparative advantage at work: capital-intensive crops in the temperate zones; labor-intensive crops in the hot zones.

But the idea was always perverse. Global trade in food makes sense in cases of genuine surplus and shortage; but it becomes problematic when it becomes the driving force behind ag policy. Why should Haiti’s farmers focus on growing mangoes, avocados, and coffee for Americans when people there lack access to sufficient food? Why should Chile’s prime farmland be occupied by flower production for the U.S.–instead of food for Chileans to eat?

Moreover, farms that have sufficient scale to profitably reach these markets tend to be huge plantations, as Paul Roberts shows in his 2008 book The End of Food. He cites the case of Kenya. In textbook terms, an emphasis on export crops looks like a raging success in Kenya–the country exports $200 million in horticultural products per year, the engine of Africa’s second-largest export economy.

And yet, smallholder farmers are increasingly iced out of that booming export market. “[T]he share of Kenya’s foreign-bound produce grown by smallholders has fallen from nearly half in 1980 to less than a sixth today,” Roberts reports. The main way most Kenyans interact with such agriculture is as plantation laborers–earning an average wage of three dollars per day.

Such arrangements don’t eliminate poverty; they enshrine it. Indeed, while laborers toil on plantations and Kenya sends literally tons of pristine fruit, vegetables, and flowers north to Europe, “about one-third of the [Kenyan] population is chronically undernourished,” the FAO reports.

So, it’s disturbing to hear Bill Clinton talking about reviving Haiti’s agriculture through export crops, and not through supporting smallholder farmers and linking them with consumers in Haiti’s cities. I love tropical crops like coffee as much as anyone; and if coffee and mango production for export can be structured in a way that boosts small-farmer incomes, then fine. But until Haiti can feed itself, the spectacle of U.S. policy titans obsessing about export markets seems absurd: farce piled on tragedy.