It seems so long ago that we had those brief, crazy flings with “junk shots,” “kill shots,” and “top kills.” Those were engineers doing improv. But there was always a net: Engineers know relief wells, we’re told, and once the two wells currently being drilled are finished in August, the problem will be solved. Now, as we tumble toward the net, a jarring question crops up: What if they don’t work?

Fred Tasker of The Miami Herald lays out how the relief wells should work — and how they could fail:

In a worst-case scenario, if drillers’ mistakes create another blow-out, the oil could spew even faster, until even more relief wells stop it or the reservoir of oil beneath it is exhausted, experts say.

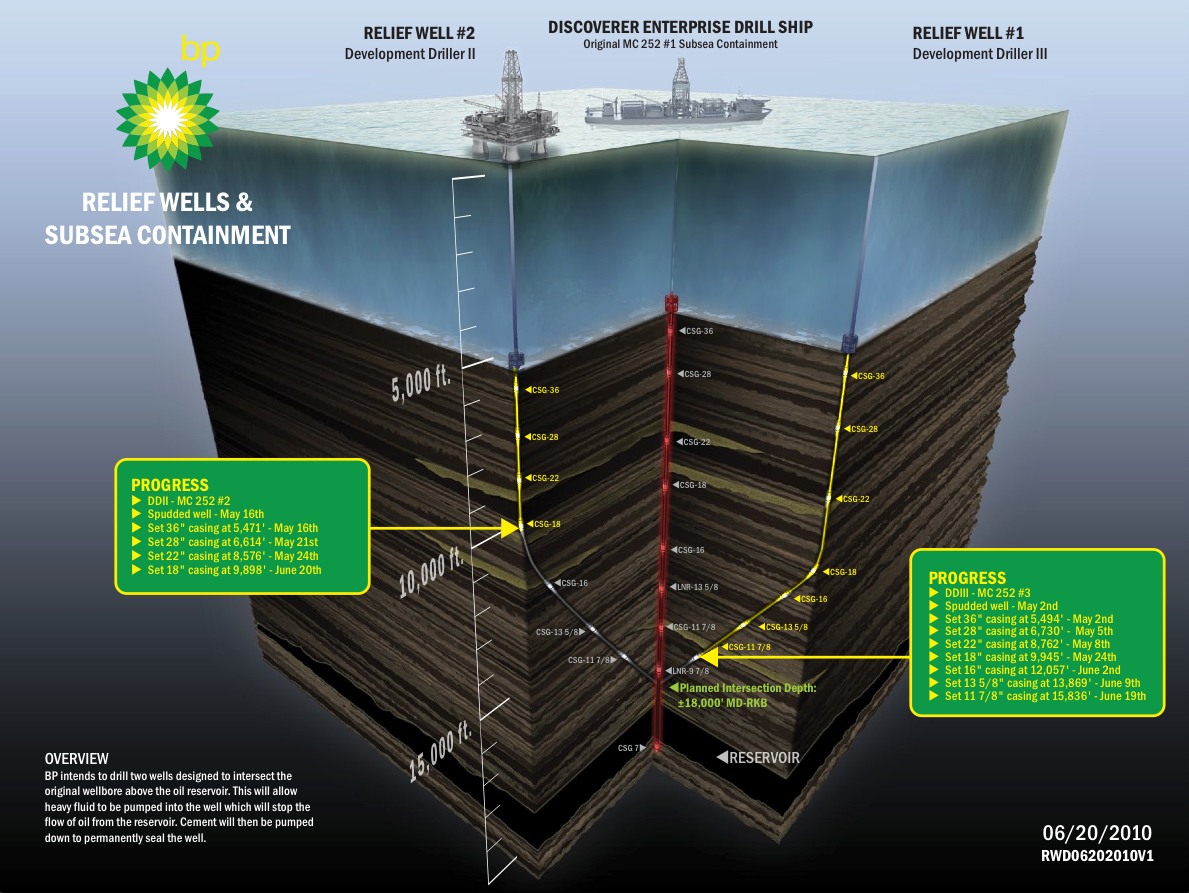

Here’s an illustration showing how the relief wells are coming along so far (or see a bigger version):

Think happy thoughts: Two spills are often cited to make the point that relief wells are tricky: the Ixtoc 1 spill near Mexico in 1979, which took almost a year to stop, and a leak off the coast of Australia last fall, which required five tries before the relief well worked.

The good news is that BP has much better of odds of succeeding. Technology has greatly improved since the former leak, and engineers have more critical data than they did for the latter. As Henry Fountain explained in The New York Times:

An oil industry expert familiar with the relief well effort said the data on the existing well was much better than the information that was available for the Australian blowout last fall. That well was an older one that was surveyed less often, making it harder for the relief well to intersect.

Backup against the wall: Yesterday, Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen mentioned for the first time that other backup plans are being hashed out in case the relief wells fail, as Jaquetta White reports in the New Orleans Times-Picayune:

Allen … shared one such plan that officials are in the early stages of studying. That involves the possibility of sucking oil from the well through a pipeline that would feed to an inactive platform nearby. From that platform, the oil could either be produced or pumped back down into the ground.

The leak that keeps on giving: Also yesterday, Allen reported a record 24-hour “capture” of oil from the leak — 25,836 barrels. But that good news was drowned out today by word that BP had to remove a cap that was containing some of the oil because of a collision involving an underwater robot, so for now the gusher is back at full force.

The way we were: In the two months since the Deepwater Horizon explosion, we’ve dramatically lowered our expectations about BP’s ability to stop the spill. Or maybe we’ve just learned to live with bad news from the Gulf. As Joel Achenbach points out in The Washington Post (writing before today’s robot incident), what was considered worst-case scenario in early May is now harsh reality:

The base-line measures of the crisis have steadily worsened. The estimated flow rate keeps rising. The well is like something deranged, stronger than anyone anticipated. BP executives last month said they had a 60 to 70 percent chance of killing it with mud, but the well spit the mud out and kept blowing.

The net effect is that nothing about this well seems crazy anymore. Week by week, the truth of this disaster has drifted toward the stamping ground of the alarmists.

The dark side: If you look at the worst-case scenario — which so far has been a pretty good call with this disaster — a combination of hurricanes, operational glitches, and problems hitting the target could mean it’s Christmas by the time the Gulf stops gushing.

Then there’s the darkest scenario of all — that the damage from the explosion is so extensive that even the relief wells won’t work. Sharon Astyk at the Casaubon’s Book blog relays that disturbing conclusion from a commenter at The Oil Drum, a blog run and frequented by oil experts:

[T]he system below the sea floor has serious failures of varying magnitude in the complicated chain, and it is breaking down and it will continue to. What does this mean? It means they will never cap the gusher after the wellhead. They cannot … the more they try and restrict the oil gushing out … the more it will transfer to the leaks below. Just like a leaky garden hose with a nozzle on it. When you open up the nozzle? … it doesn’t leak so bad, you close the nozzle? … it leaks real bad, same dynamics. It is why they sawed the riser off … or tried to anyway … but they clipped it off, to relieve pressure on the leaks “down hole”. [Ellipses in original.]

How do you spell relief?