That we are close to a peak in global oil production should not be a surprise to anyone, but some leaked documents have made the situation even clearer, as the Guardian reports:

That we are close to a peak in global oil production should not be a surprise to anyone, but some leaked documents have made the situation even clearer, as the Guardian reports:

The U.S. fears that Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest crude oil exporter, may not have enough reserves to prevent oil prices escalating, confidential cables from its embassy in Riyadh show.

The cables, released by WikiLeaks, urge Washington to take seriously a warning from a senior Saudi government oil executive that the kingdom’s crude oil reserves may have been overstated by as much as 300 billion barrels — nearly 40 percent.

The bombshell is that the U.S. Embassy in Riyadh understands this and that it “now questions how much the Saudis can now substantively influence the crude markets over the long term.” Who persuaded them of this is equally remarkable — Sadad al-Husseini, “a geologist and former head of exploration at the Saudi oil monopoly Aramco,” who says he isn’t in the peak oil camp but sounds on awful lot like those of us who are.

Consider the first cable, from Dec. 2007:

On Nov. 20, 2007, CG and Econoff met with Dr. Sadad al-Husseini, former executive vice president for exploration and production at Saudi Aramco. Al-Husseini, who maintains close ties to Aramco executives, believes that the Saudi oil company has oversold its ability to increase production and will be unable to reach the stated goal of 12.5 million barrels per day of sustainable capacity by 2009. While stating that he does not subscribe to the theory of “peak oil,” the former Aramco board member does believe that a global output plateau will be reached in the next five to 10 years and will last some 15 years, until world oil production begins to decline. Additionally, al-Husseini expressed the view that the recent surge in oil prices reflects the underlying reality that global demand has met supply, and is not due to artificial market distortions.

Triple wow.

First off, the guy who was in charge of exploration at Sauid Aramco says they have oversold their sustainable peak capacity. Second, while he said he doesn’t believe in peak oil, he lays out a peak oil scenario. Third, he believes it wasn’t speculators but market realities that drove up prices.

Here are more details on his underlying rationale:

First, it is possible that Saudi reserves are not as bountiful as sometimes described and the timeline for their production not as unrestrained as Aramco executives and energy optimists would like to portray. In a Dec. 1 presentation at an Aramco Drilling Symposium, Abdallah al-Saif, current Aramco Senior Vice President for Exploration and Production, reported that Aramco has 716 billion barrels (bbls) of total reserves, of which 51 percent are recoverable. He then offered the promising forecast — based on historical trends — that in 20 years, Aramco will have over 900 billion barrels of total reserves, and future technology will allow for 70 percent recovery.

Al-Husseini disagrees with this analysis, as he believes that Aramco’s reserves are overstated by as much as 300 billion bbls of “speculative resources.” He instead focuses on original proven reserves, oil that has already been produced or which is available for exploitation based on current technology. All parties estimate this amount to be approximately 360 billion bbls. In al-Husseini’s view, once 50 percent depletion of original proven reserves has been reached and the 180 billion bbls threshold crossed, a slow but steady output decline will ensue and no amount of effort will be able to stop it. By al-Husseini’s calculations, approximately 116 billion barrels of oil have been produced by Saudi Arabia, meaning only 64 billion barrels remain before reaching this crucial point of inflection. At 12 million barrels per day production, this inflection point will arrive in 14 years. Thus, while Aramco will likely be able to surpass 12 million barrels per day in the next decade, soon after reaching that threshold the company will have to expend maximum effort to simply fend off impending output declines. Al-Husseini believes that what will result is a plateau in total output that will last approximately 15 years, followed by decreasing output. [Emphasis mine.]

Of course, many people believe that the peak will come somewhat sooner, but whether we are peaking now or later in the decade matters little to our urgent need to get off of oil if we are to avert severe economic dislocation.

The supply and demand trends are inexorable:

Global oil prices: Demand has met supply

Considering the rapidly growing global demand for energy — led by China, India, and internal growth in oil-exporting countries — and in light of the above mentioned constraints on expanding current capacity, al-Husseini believes that the recent oil price increases are not market distortions but instead reflect the underlying reality that demand has met supply (global energy supply having remained relatively stagnant over the past years at approximately 85 million barrels per day). He estimates that the current floor price of oil, removing all geopolitical instability and financial speculation, is approximately $70-75 per barrel. Due to the longer-term constraints on expanding global output, al-Husseini judges that demand will continue to outpace supply and that for every million barrel per day shortfall that exists between demand and supply, the floor price of oil will increase $12. Al-Husseini added that new oil discoveries are insufficient relative to the decline of the super-fields, such as Ghawar, that have long been the lynchpin of the global market …

He stated that the IEA’s expectation that Saudi Arabia and the Middle East will lead the market in reaching global output levels of over 100 million barrels per day is unrealistic, and it is incumbent upon political leaders to begin understanding and preparing for this “inconvenient truth.” [Emphasis mine.]

Ah, I would love to have been in the room when al-Husseini used that phrase.

I will add that I have talked to other leading experts on the international oil market and they are exceedingly dubious that we can get to 100 million barrels a day. Indeed, some think going much past 90 million barrels a day would be difficult:

Al-Husseini was clear to add that he does not view himself as part of the “peak oil camp,” and does not agree with analysts such as Matthew Simmons. He considers himself optimistic about the future of energy, but pragmatic with regards to what resources are available and what level of production is possible. While he fundamentally contradicts the Aramco company line, al-Husseini is no doomsday theorist. His pedigree, experience, and outlook demand that his predictions be thoughtfully considered. [Emphasis mine.]

Somehow I doubt the Bush administration thoughtfully considered any of this.

The Guardian notes that “seven months later, the U.S. embassy in Riyadh went further in two more cables“:

Our mission now questions how much the Saudis can now substantively influence the crude markets over the long term. Clearly they can drive prices up, but we question whether they any longer have the power to drive prices down for a prolonged period.

The consequences of the multi-decade effort by conservatives to block a sensible U.S. energy policy are nigh.

Note: The Guardian also writes:

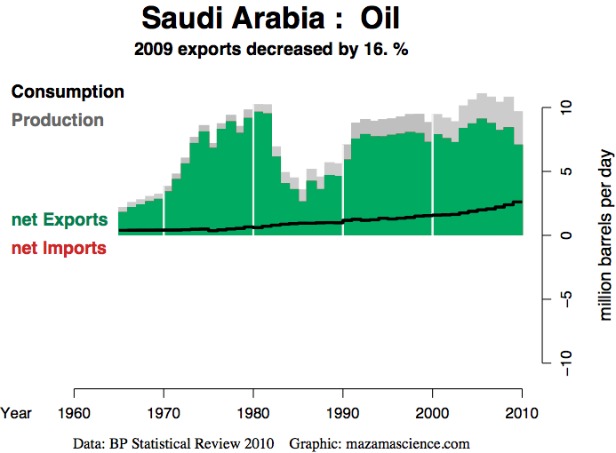

A fourth cable, in Oct. 2009, claimed that escalating electricity demand by Saudi Arabia may further constrain Saudi oil exports. “Demand [for electricity] is expected to grow 10 percent a year over the next decade as a result of population and economic growth. As a result it will need to double its generation capacity to 68,000 megawatts in 2018,” it said.

But I don’t see that quote in that cable.

Oil Drum has supporting analysis, with this great figure:

Exports, in green, are down because Saudi Arabia is consuming more and more of its own oil, so there is less available for others.