Nemonte Nenquimo was just 6 years old when she heard the hum of a plane overhead bringing white people to her village in the Amazon. Nenquimo is Indigenous Waorani, and she has spent the last decade of her life fighting the efforts of oil companies to drill her land.

She’s had enormous success: She led a lawsuit against planned oil drilling and won, protecting half a million acres of Amazon rainforest. She helped push for a national referendum to ban oil drilling in Yasuni National Park in Ecuador, which won resoundingly. Her work also set a legal precedent defending Indigenous rights.

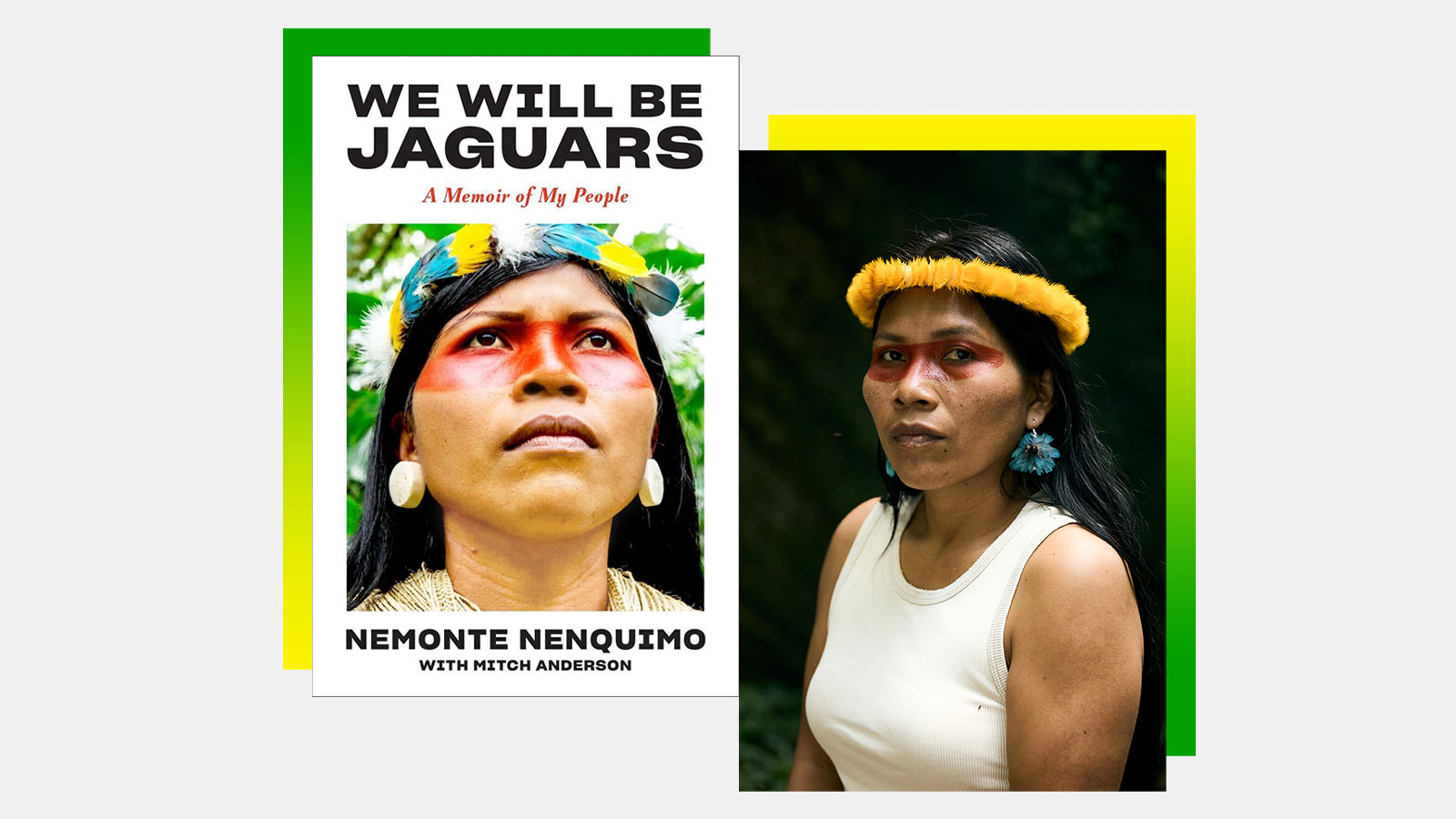

This fall, she released a memoir called “We Will Be Jaguars,” chronicling her life story. The book has just been named this month’s pick for actress Reese Witherspoon’s book club. Nenquimo is also continuing to fight Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa’s efforts to continue oil extraction.

Grist spoke with Nenquimo to learn more about her work. Her answers were translated from Spanish and have been condensed for clarity.

Q. How is climate change affecting your people?

A. The trees that normally fruit that feed and nourish the monkeys are not fruiting, and the monkeys are now raiding the gardens of the village. The river turtles, because of changes in the seasons, aren’t finding the right time to lay eggs on the beaches. My people notice very small and important changes in their ecosystem that the rest of the world doesn’t understand. The rest of the world needs huge hurricanes or big floods to think, ‘This is the climate crisis.’ But my father always told me that the climate crisis is the language of Mother Earth. It’s Mother’s way of communicating to the people about what she’s experiencing, how she’s changing, what she’s suffering.

Everyone is speaking about the urgency of the climate crisis, but it’s really just the world leaders and the business leaders that are in the rooms making decisions. There isn’t really a true understanding that Indigenous peoples and local communities on the front lines are stewarding and protecting their lands. They need to be not only involved with seats at the table but need to be guiding and steering those conversations.

Q. Can you tell us more about your impression of those international climate conversations and their connection to what’s happening in your home country?

A. I was at COP and saw there were Indigenous leaders that were there, but they were there without spaces to speak. They traveled very far but they weren’t really able to get into the conference. And at the same time, it was a space where nearly 200 countries made an agreement to transition away from fossil fuels. And when I returned to the Amazon, the first thing that I saw in the Amazon was my government, who had agreed to transition away from fossil fuels, doubling down on oil and making plans to launch another oil auction across the entire south-central Amazon.

That just confirmed that in the climate conferences, it’s still a colonial structure where world leaders and governments and businesses are the ones steering the conversation and making decisions. A lot of the promises are false promises. I’m very convinced that world leaders and the economic system are hell-bent on continuing to extract oil for as long as they can extract oil.

Q. What lessons do you think other Indigenous activists can take away from your advocacy?

A. First, it’s important to dream with your people, and to really build a vision for many generations of your people, because ultimately to win and to confront the forces that are threatening our lands and our livelihoods, we need to be unified and we need to be a powerful collective, and that starts with really listening and building a strong vision and a strong dream for your community and the people.

The second piece of advice I would give to young Indigenous activists is to focus on your own spirituality and your own connection to the Earth and to your culture and to your territory, because we carry a lot of traumas. The world is very confusing and the world is very powerful and it’s easy to get wrapped up and sucked up, churned up, spit out by the world outside your territories. And so to really have a strong spiritual foundation and spiritual fortitude is a really powerful and important component of being a powerful and successful Indigenous warrior.

And then finally, to really look to build honest, authentic and powerful collaborations with non-Indigenous people, not to allow and permit outsiders to design and lead and propose top-down solutions, but to really seek out harnessing and building really truthful collaborations with folks from outside your territory or Western organizations and activists. Really make sure that they’re committed to listening and learning and respecting your vision, your dreams, and your rhythms.

Q. What tools would you say have been critical to your success thus far?

A. Firstly, leveraging our rights — our international rights to require informed consent, our right to decide what happens in our territories — was a really powerful strategy to protect our lands because we were able to challenge the government’s designs over our territories and their efforts to auction off our lands without our permission.

At the same time, we needed to leverage communication strategies and social media and networks of allies, including celebrities, Indigenous rights experts, and people from around the world to support us, stand in solidarity with us, and shine a spotlight on the judicial system to ensure that we could protect outcomes and protect the integrity of the process.

Also, building out the capacity of Indigenous organizations to manage resources is another important tool, for the protection of our homelands and to really build out and design strategies that work for us.

And then ultimately it was the leveraging of new technologies and combining that with our own people’s knowledge and wisdom of our own forests and our territories. The governments and the companies tend to see our homelands as just a place to extract resources, our homelands as commodities, as almost sort of empty places waiting to be turned into productive zones, when in reality our territories are an intricate web of life that sustains our cultures and that sustains our planet’s climate and biodiversity. And so we created intricate territorial maps using new technologies, walking with the elders and the youth in the forests to tell the story of our land and ultimately show that our land is ours and to provide depth to the rights that we already have to decide what happens in our land.

Q. What prompted you to write your book?

A. My people come from a long tradition of oral storytelling stories that have been passed down for centuries across the generations. But the reason I decided to write a book was because for many years, we have been working to build a movement to protect Indigenous territories and cultures from extractive violence and from conquest and colonialism, and have won a lot of important victories, but the threats continue to come. My father said the elders always say that the outsiders always destroy what they don’t understand and that the story dies when no one tells it.

It’s an important time for me to write my story and for it not to be people from the outside telling the story but my own voice and as a way to create an opportunity for the outside world to learn about my people and the connection they have with the land. Because the people that come from the outside, they either destroy what they don’t understand or they try to help what they don’t understand. And either way, they cause harm.

And it was also an effort to create a story that the Waorani children could listen to, and feel proud of.

Q. As you continue to fight oil drilling in your territories, how would you characterize what is at stake?

A. Life is at stake. Our culture, our knowledge, our connection with the land and water, the forest, the wildlife. Ultimately, if the governments and the companies achieve what they want to achieve, which is the destruction of our cultures and of our lands, they’ll also create a worsening climate crisis and trigger these tipping points around the world. And what I’m trying to do is share my story and my people’s story with the world, to wake up the world so they can understand that what’s at stake is life itself and that if we continue to build economies based on infinite growth and endless consumption then we’re going to destroy the very Mother who is giving us life.

I really do believe in the power of the people and civil society and citizens around the world to wake up and realize the stakes of the climate crisis and to realize that action needs to happen now and Nin their own communities. It starts with each and every one of us in our communities building community, building the power to change the system.

Correction: This story originally misspelled Waorani.