This story was originally published by Atlas Obscura and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Climate change doesn’t just happen in the air, in the dirt, or in the fearsome pages of damning studies. It happens before our eyes.

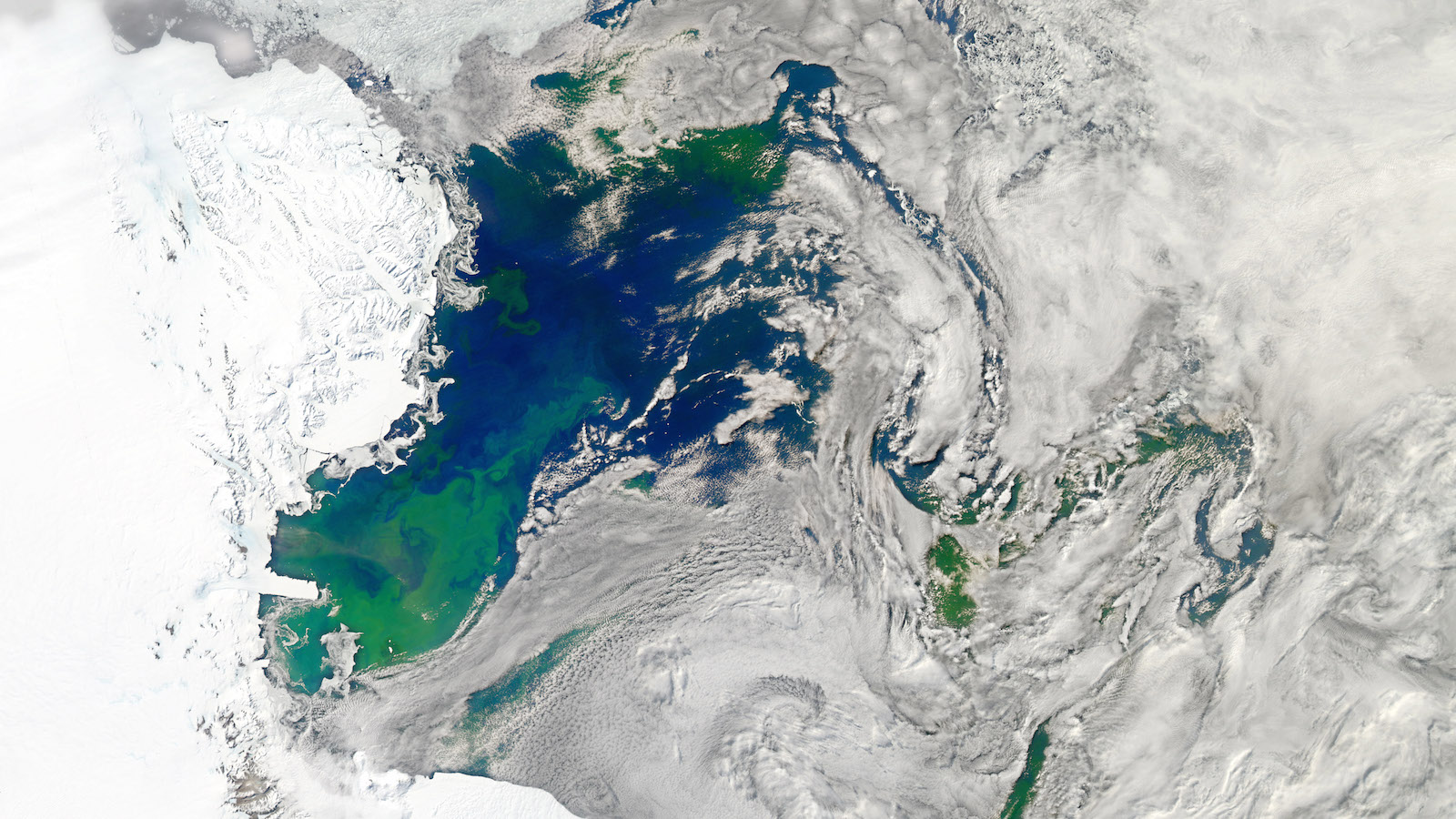

And so, as our planet continues to warm, our oceans will turn deeper shades of blue and green, according to research published Monday in the journal Nature Communications. The changes in color are in part a function of the fluctuating populations of phytoplankton, or algae — the microscopic plants that, across their thousands of different species, do some rather heavy lifting for the global ecosystem. Running a model through the end of this century, the researchers estimate that more than 50 percent of the world’s oceans will exhibit changes in color by the year 2100, as their algae populations rise and fall.

Because every species is different, climate change will wreak different effects on different communities of phytoplankton. In the subtropics, for example, the waters are expected to become more blue as the population of algae falls. Waters near the poles, on the other hand, are expected to turn deeper shades of green as the warmer conditions beckon the algae to boom. More algae means more green because their chlorophyll pigments — the ones that absorb sunlight for photosynthesis — absorb more of the blue end of the electromagnetic spectrum, and less of the green. Water itself does not absorb blue light, so the emptier it is, the bluer it will be.

The research builds upon earlier models, in use since the 1990s, in which scientists derived water’s chlorophyll levels based on the colors in satellite images. But this method did not provide a complete picture, says Anna Hickman, an oceanographer at the University of Southampton in England, and a coauthor of the new study.

Chlorophyll levels could suggest what was going on with phytoplankton populations, but not necessarily with the other organisms making up a diverse marine community, reflecting and absorbing light on their own terms. Chlorophyll levels could also be skewed by isolated weather events that temporarily tweak algae populations, but which don’t necessarily evince the systemic workings of climate change, said Stephanie Dutkiewicz, the study’s lead author, in a press release. The new model uses color to analyze the light itself as it’s being reflected and absorbed by everything in the water, and not only to analyze the presence of chlorophyll. The researchers watched the colors change in the model as they raised the temperature by 3 degrees C — an increase that, judging by current trends, could really occur by 2100.

Hickman says that the changes in color may not be noticeable to the naked human eye, however clear they are to satellites. But other changes in the water could be all too apparent: Where algae populations fall and fish have less to eat, global fish catch could decline by 20 percent by the year 2300, according to the World Economic Forum.