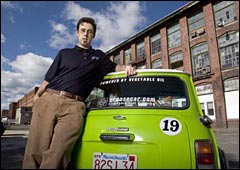

Justin Carven.

In the span of just two years, Justin Carven invented the first waste-oil conversion kit for diesel engines, graduated from Hampshire College, drove a vegetable-oil-fueled van across the country, and started his very own company. Six years later, Greasecar Vegetable Fuel Systems is selling so many conversion kits that Carven is talking about setting up franchises in India and Brazil. Grist talked to him about the etiquette of snagging free waste oil, Iraq vets’ conversion to veggie oil, the economics of environmental goodness, and more.

How did you first get interested in biofuels?

I went to Hampshire College, and while I was there I worked with a guy named Carl Bielenberg who had an organization called the Better World Workshop up in Vermont. He had been doing work for years in West Africa developing hand-operated oil-seed presses for producing edible oils and experimenting with using those vegetable oils as an alternative diesel fuel. I had done some fieldwork in Pakistan and Kenya trying to evaluate the potential of bringing the technology over there, but met with a lot of resistance because it was experimental. That’s when I realized that the best way to push this technology forward was to commercialize it domestically.

At the time, diesel prices were not much over a dollar, and brand new vegetable oil was $4 or $5 a gallon. So we had to identify another source that was affordable enough to use as fuel. There was an emerging biodiesel community developing, and a lot of people were getting waste cooking oil from restaurants and processing it with chemicals to make biodiesel fuel. I figured, why can’t we do that? I took it upon myself to experiment on a Volkswagen diesel. The following year, I purchased a Volkswagen camper van and outfitted it with a converted diesel engine and took a cross-country trip running on vegetable oil. We got so much response from the trip that when I came back, I decided to design a conversion-kit product.

On that first cross-country trip, how hard was it to get the restaurants to give you their cooking oil? Did the owners think you were crazy?

For the most part, people were really excited about it and would offer us free lunch or invite us in for drinks just so they could hear the story. Now there are thousands of people out there trying to do this in the U.S., so we have a whole thing on our website to explain the ways to approach restaurants and be courteous. We don’t want to tick people off — the last thing we want is a huge mess behind restaurants.

In the long run, we need to start developing an infrastructure. We do have a number of folks who have contracts with restaurants and are processing the oil to a high standard and distributing it. But what’s made the biofuel movement so successful is that people are able to go source the fuel independently up the street, without waiting for large manufacturers to develop synthetic fuels.

So what’s your typical customer like?

It’s not the clichéd demographic that a lot of people would imagine. We have soldiers coming back from Iraq who want to make a change in their lives after seeing what they’ve seen, and they do it for political reasons. We have commercial applications that are doing it to save money and to create a little bit of PR. More so than environmentalists, we have people who are trying to save money.

It wasn’t really until fuel prices started taking off that people started putting their money where their mouths were. Even folks who want to say they’re doing it for environmental reasons didn’t do it until it hit them in the pocketbook.

Do you still have that VW camper van? If not, what kind of car do you drive?

No, I sold the van a few years ago. Right now, I have a 2001 Golf and an old 1980 British Mini car that we put a diesel engine in. Unfortunately, the market for used diesel vehicles has gone through the roof. The same old Volkswagens that I used to buy for a hundred dollars a few years ago are selling now for three or four or five thousand dollars.

Anytime there’s something like this going on, there are always profiteers. But we haven’t changed our product price in six years, even though the product we sell now for $800 is much higher quality and a little more expensive than the product we sold five years ago. We’re trying not to jump on the greedy profiteering bandwagon.